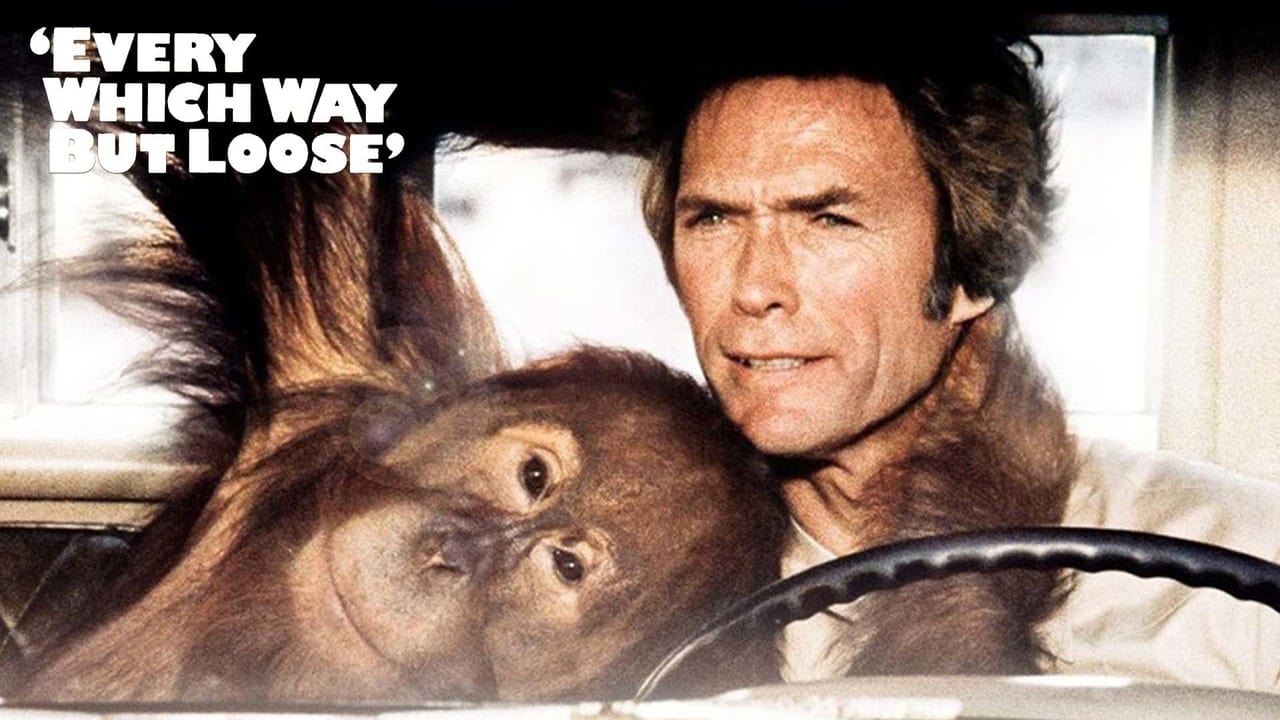

Alright, rewind your minds back to the glorious clutter of the video store shelves. Amidst the explosive action covers and moody thrillers, there was always that slightly baffling box: Clint Eastwood, looking tough as nails, standing next to... an orangutan? 1978’s Every Which Way but Loose was a curveball nobody saw coming, least of all the critics who dismissed it, only to watch it become one of the biggest smashes of Clint’s entire career and a permanent fixture on the “Most Rented” wall throughout the 80s.

### Bare Knuckles and a Bottle of Beer

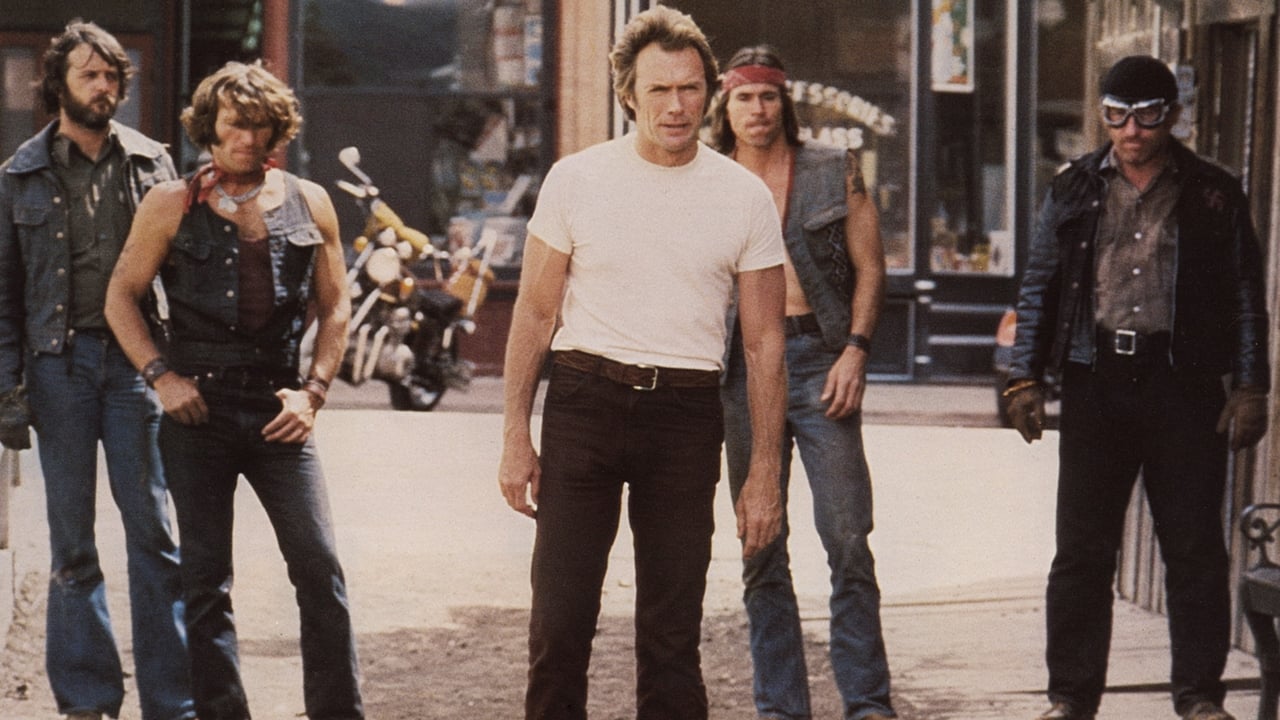

Let's be clear: this isn't Dirty Harry trading existential barbs with Scorpio. This is Philo Beddoe (Clint Eastwood), a good-natured trucker and arguably the best bare-knuckle fighter west of the Rockies, drifting through life in the San Fernando Valley with his buddy Orville (Geoffrey Lewis, a frequent and always welcome face alongside Eastwood) and his scene-stealing orangutan, Clyde. The plot, such as it is, involves Philo getting smitten by aspiring country singer Lynn Halsey-Taylor (Sondra Locke) and chasing her across the American West, getting into scrapes with bikers (the gloriously inept Black Widows), cops, and rival fighters along the way.

It's a shaggy-dog story, pure and simple, fueled by cheap beer, country music, and the sheer charisma of its star doing something completely unexpected. Eastwood, reportedly taking the role against the advice of pretty much everyone, saw the potential for fun and a connection with a blue-collar audience. He wasn't wrong. Warner Bros. must have plotzed when this reportedly $5 million picture raked in over $100 million (that's pushing half a billion in today's money!), cementing Eastwood's status as a megastar who could literally do anything and sell tickets.

### The Punch is Real (Mostly)

Now, let's talk action. Forget the slick, hyper-edited fights of today. The brawls in Every Which Way but Loose have that raw, grounded feel that defined so much 70s and 80s action filmmaking. These aren't graceful martial arts displays; they're sloppy, powerful slugfests. You feel the weight behind the punches, the exhaustion, the sheer grit of it all. Remember how real those thuds sounded coming out of your CRT TV speakers?

Director James Fargo, who’d previously directed Eastwood in the Dirty Harry entry The Enforcer (1976), keeps things straightforward. The camera doesn't do frantic flips; it captures the impact. It’s all practical – real bodies hitting dusty ground, maybe a breakaway table or two. Sure, it looks dated compared to the complex choreography we see now, but there's an undeniable authenticity to it. You believed these guys were really swinging for the fences, relying on stunt performers earning their paychecks the hard way, not digital doubles. I distinctly remember watching these fights as a kid, wide-eyed at the sheer physicality, long before I understood the difference between a pulled punch and CGI enhancement.

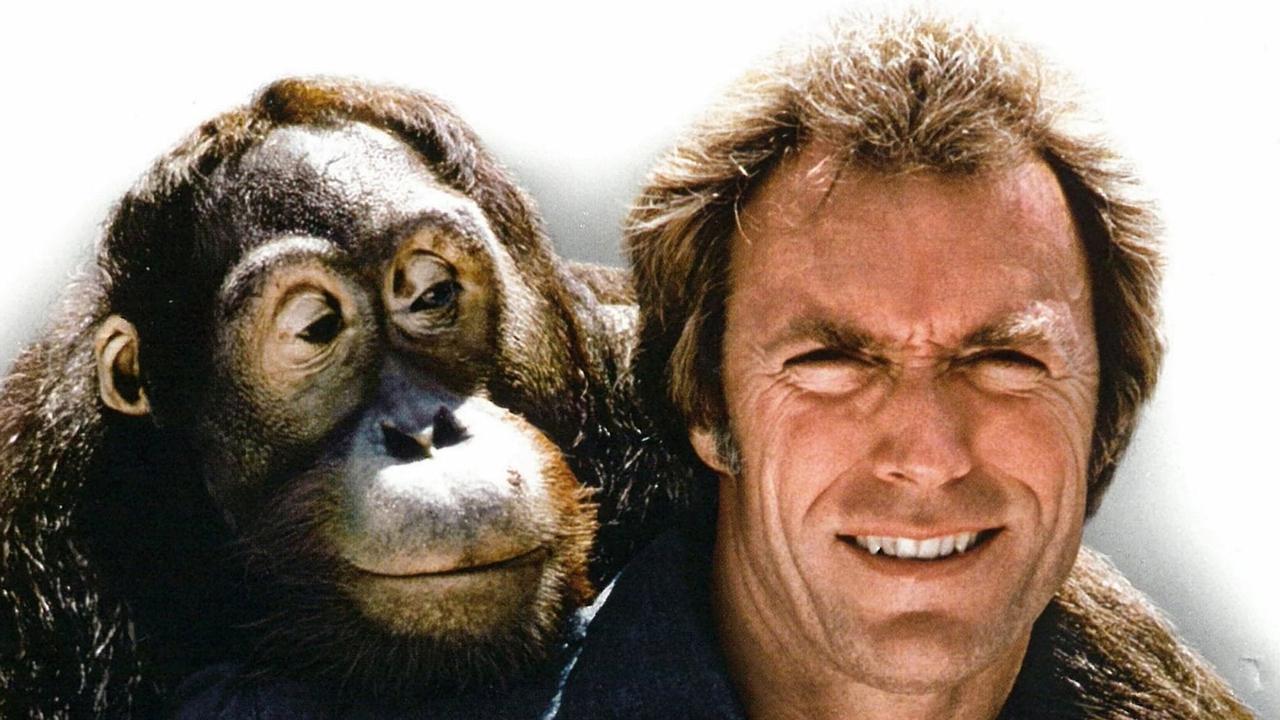

### That Orangutan Though…

And then there's Clyde. Played primarily by a talented orangutan named Manis (under the guidance of his dedicated trainer), Clyde isn't just a gimmick; he's a character. His right hooks are legendary, his fondness for beer relatable, and his interactions with Philo provide the film's heart and a lot of its biggest laughs. Was it absurd? Absolutely. Did it work? Somehow, yes. The sheer novelty of seeing Eastwood pal around with an ape was a massive hook, and Clyde delivers genuine comedic moments. You just knew finding this tape at the rental store meant you were in for something… different. Integrating an animal actor so prominently was a risk, but Manis proved remarkably adept, becoming an unlikely movie star in his own right.

### Country Roads and Critical Scorn

The film is drenched in the sounds of late-70s country music, featuring hits from the likes of Eddie Rabbitt ("Every Which Way but Loose") and Mel Tillis. It perfectly complements the dusty roads, roadside bars, and blue-collar milieu. Geoffrey Lewis is fantastic as the slightly hapless Orville, always ready with a scheme or a beer, and Sondra Locke (a frequent Eastwood collaborator and partner at the time) provides the elusive object of Philo’s affection, though her character remains somewhat thinly sketched.

Critics at the time mostly savaged it. They couldn’t reconcile the tough-guy icon with this goofy, rambling comedy. But audiences didn't care. They turned up in droves, connecting with the unpretentious charm, the easygoing humor, and, yes, the fighting orangutan. It tapped into something primal and fun, a perfect slice of escapism that felt tailor-made for repeat viewings on VHS. It even spawned a successful sequel, Any Which Way You Can (1980), proving Philo and Clyde had staying power.

---

VHS Heaven Rating: 7/10

Justification: While it’s undeniably goofy and the plot meanders like a drunken trucker, Every Which Way but Loose delivers exactly what it promises: laughs, some satisfyingly crunchy bare-knuckle brawls, and the singular charm of Clint Eastwood sharing the screen with an orangutan. It’s a huge slice of late-70s/early-80s pop culture comfort food, elevated by Eastwood’s effortless charisma and the film's sheer, unpretentious weirdness. The practical fights feel refreshingly grounded, and the country soundtrack is pitch-perfect. It loses points for a thin central romance and some repetitive gags, but its massive success and enduring nostalgic appeal are undeniable.

Final Thought: Critics scratched their heads, but audiences knew best – sometimes, all you need is Clint, Clyde, and a couple of cold ones for a genuinely good time. A true video store legend that’s still surprisingly watchable, right down to its fuzzy, analog soul.