Okay, fellow tape-heads, let’s rewind to a time when historical epics often felt… well, epic, but perhaps a little self-important. Now, imagine taking that scale, those chariots, those togas, and injecting it with a dose of pure, unadulterated French absurdity. That peculiar flicker you might just remember from a dusty rental shelf is Jean Yanne's 1982 creation, Quarter to Two Before Jesus Christ (Deux heures moins le quart avant Jésus-Christ), a film that gleefully thumbs its nose at reverence while simultaneously borrowing its grandest costumes.

Sand, Sandals, and Satire

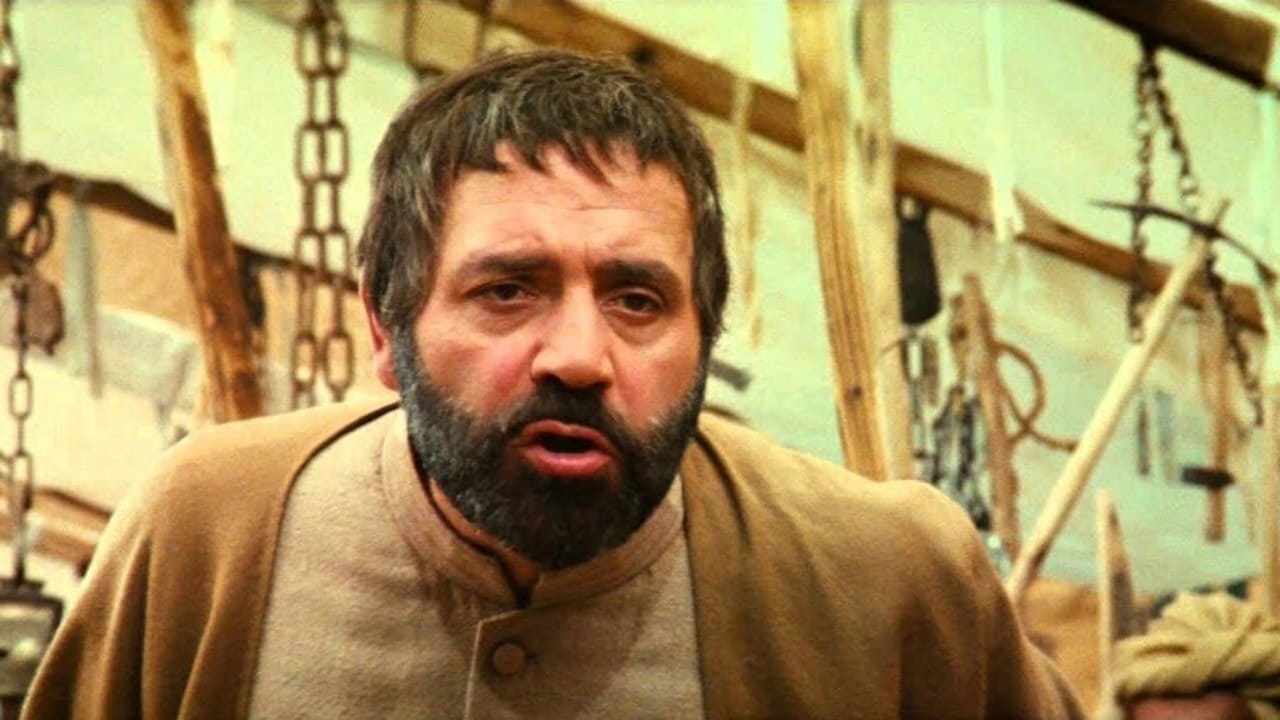

The premise transports us to a ridiculously named Roman colony in North Africa – "Rahatlocum" (a pun on Turkish Delight, Loukoum) – a place that looks suspiciously like the sets leftover from grander, more serious productions. Here, the narrative loosely orbits Ben-Hur Marcel, played by the legendary French comedian Coluche. Forget Charlton Heston's stoic intensity; Coluche, a national icon in France known as much for his anti-establishment wit (he even mounted a satirical presidential bid in 1981) as his comedic timing, brings a bumbling, everyman charm to the role. He’s less a hero destined for greatness and more a hapless mechanic caught in the ludicrous political machinations between a delightfully neurotic Julius Caesar (Michel Serrault) and a scheming Cleopatra (Mimi Coutelier).

What unfolds isn't so much a coherent plot as a series of anarchic sketches draped in Roman garb. Director Jean Yanne, who also appears as the wonderfully cynical tour guide Paulus, doesn’t just wink at the camera; he practically mugs for it, shattering the fourth wall with abandon. This isn't Mel Brooks' History of the World, Part I (1981) broad strokes; it’s distinctly French, steeped in wordplay (much of which, alas, gets lost in translation), pointed political jabs aimed squarely at contemporary France, and a relentless barrage of anachronisms. Think Roman soldiers checking their watches, chariots sporting sponsor logos like Formula 1 cars, and discussions peppered with modern slang and bureaucratic jargon.

Caesar's Camp and Coluche's Clowning

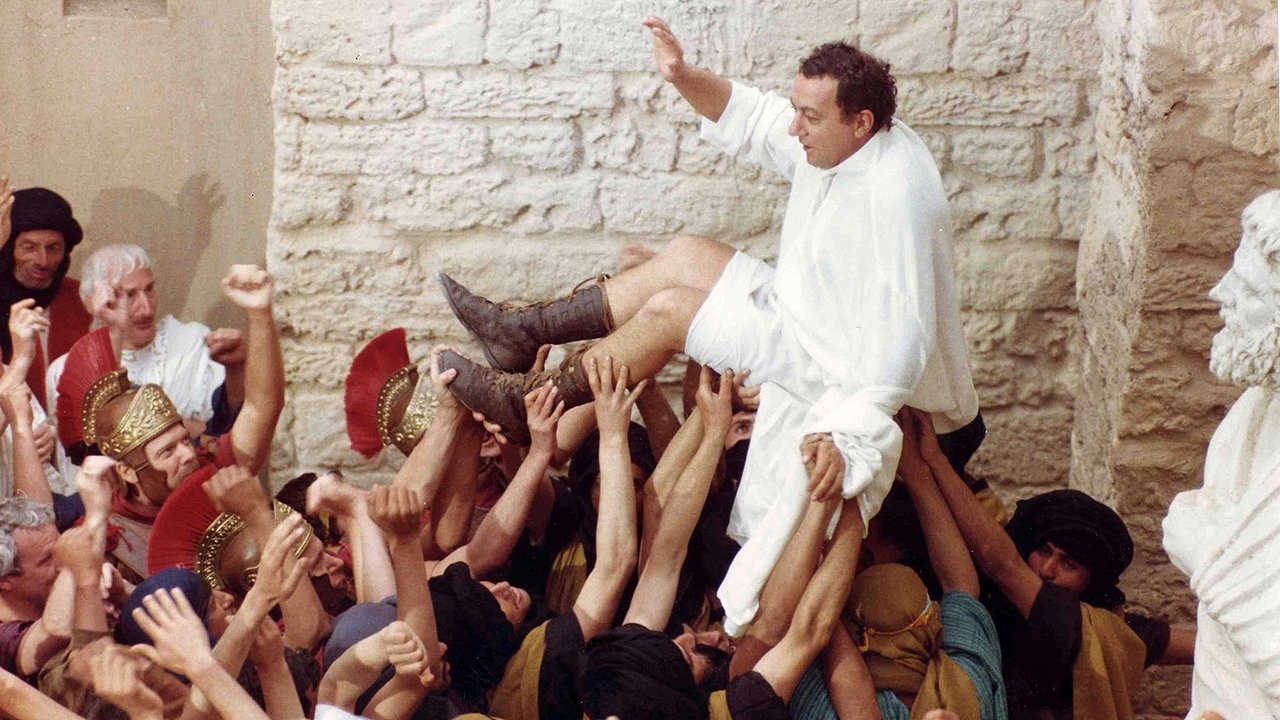

The film truly belongs to its central performers. Coluche is effortlessly funny, embodying the bewildered citizen overwhelmed by nonsensical authority. His physicality and timing are superb, even when navigating dialogue that might baffle non-francophones. But it’s Michel Serrault, perhaps best known internationally for his stunning turn in La Cage aux Folles (1978), who steals every scene he’s in. His Caesar isn't a commanding emperor but a preening, insecure, utterly camp dictator obsessed with his image and prone to petulant outbursts. Serrault leans into the absurdity with gusto, delivering lines about military strategy with the same theatrical flair he uses to fret about his laurel wreath. Seeing these two titans of French comedy spar amidst the faux-Roman splendor is the film’s primary joy.

Behind the Togas

Quarter to Two was a colossal hit in France, drawing over 4.6 million viewers – a testament to the star power of Coluche and Serrault, and the French appetite for Yanne's brand of pointed satire. Filmed largely in Tunisia, utilizing locations familiar from more earnest historical films, the production deliberately juxtaposes the epic scale with lowbrow gags and surprisingly sharp commentary. The advertising billboards plastered everywhere ("Pompeii: A City With a Future!") aren't just visual jokes; they're digs at consumer culture and political spin, reflecting anxieties very much alive in early 80s France. It’s fascinating how Yanne, known for his often cynical and provocative work (like Moi y'en a vouloir des sous from 1973), uses the historical setting not just for parody, but as a Trojan horse for contemporary critique. One story goes that the sheer number of extras required for some scenes nearly rivaled those of actual epics, adding another layer of irony to the budget-conscious absurdity of the plot.

Does the Joke Still Land?

Watching it today on a format far removed from the original VHS, how does Quarter to Two hold up? Well, it’s undeniably dated in places. Some gags rely heavily on specific French cultural or political references of the time that might fly over the heads of international viewers. The relentless pace of jokes means not all of them land, and the translated subtitles, if you rely on them, can sometimes struggle with the rapid-fire wordplay. I recall renting this years ago, drawn by the promise of a historical comedy, and being utterly bewildered yet strangely captivated by its sheer Gallic nerve.

Yet, there's an infectious energy here. The commitment of the cast, particularly Serrault's unhinged Caesar, remains genuinely funny. The central satirical thrust – poking fun at political pomposity, media manipulation, and historical revisionism – still resonates. It’s a film that feels both incredibly specific to its time and place, yet universal in its mockery of power. It doesn't aim for subtle wit; it throws everything at the wall, and enough of it sticks to make for a uniquely memorable viewing experience. It’s less a tightly structured comedy and more a chaotic, joyous mess – a party in togas where everyone seems slightly drunk on the absurdity of it all.

Rating: 6/10

Justification: Quarter to Two Before Jesus Christ scores points for its sheer audacity, the brilliant comedic performances of Coluche and especially Michel Serrault, and its unique place in French cinematic satire. It successfully parodies the historical epic genre while landing some surprisingly sharp blows. However, its reliance on culturally specific humor and wordplay means its impact is lessened for non-French audiences, and the scattershot approach leads to uneven pacing and jokes that haven't aged gracefully. It's a fascinating, often hilarious, but flawed piece of 80s absurdity.

Final Thought: It might not be the slickest or most universally accessible parody from the era, but pulling this tape off the shelf was like unearthing a strange, uniquely French artifact – a reminder that historical satire could be loud, messy, and delightfully weird. What lingers isn't just the gags, but the bold, almost defiant spirit of its humor.