Okay, dim the lights, maybe pour yourself something strong. Let that familiar static hum of the VCR fill the room for a moment. We're diving into a tape that doesn't just play; it stares back. John Carpenter's 1995 descent into cosmic dread, In the Mouth of Madness, wasn't just another horror flick stacked on the rental shelves. It was a question whispered from the flickering screen: what if the stories we consume start consuming us? This wasn't just part of Carpenter's unofficial "Apocalypse Trilogy" (alongside The Thing and Prince of Darkness); it felt like the final, chilling chapter on reality itself dissolving.

### Reality is Not What It Used to Be

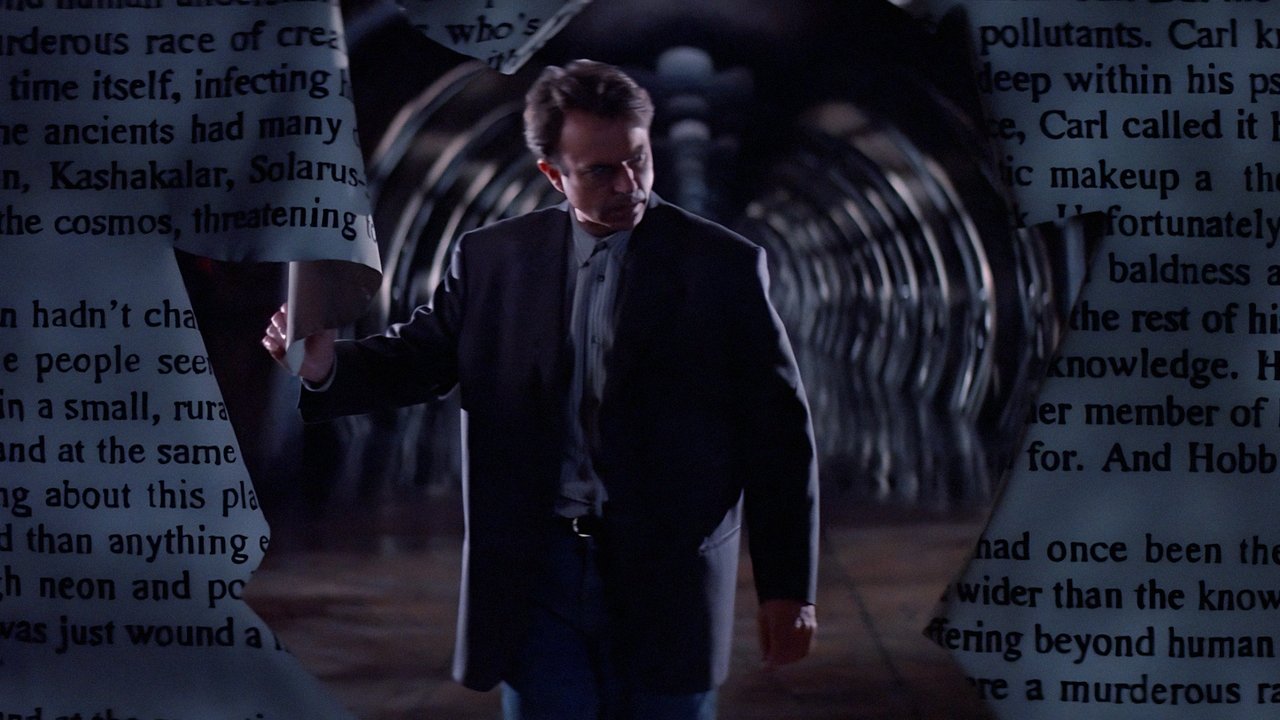

The premise grips you with cold, insistent fingers. Insurance investigator John Trent (Sam Neill, fresh off dodging dinosaurs in 1993's Jurassic Park but finding something far more existentially terrifying here) is hired to find Sutter Cane (Jürgen Prochnow, radiating sinister charisma), a horror novelist whose work drives readers quite literally insane. Cane has vanished just before delivering his latest manuscript, potentially triggering a massive insurance claim. Trent, a cynical pragmatist, dismisses Cane's effect as mass hysteria, a marketing gimmick gone wild. Paired with Cane's editor, Linda Styles (Julie Carmen), Trent follows cryptic clues hidden in Cane's book covers, leading them to a town that shouldn't exist: Hobb's End, New Hampshire – the very setting of Cane's novels.

What unfolds isn't a typical investigation. It's a slow, sanity-shredding slide into a world governed by Cane's prose. The film masterfully blurs the lines. Is Trent losing his mind, or is reality itself being rewritten by a mad author who might just be a conduit for something far older and darker? This central ambiguity is the engine driving the film's profound unease. Michael De Luca's script, which had reportedly been circulating in Hollywood for years before Carpenter brought his signature touch, taps directly into that primal fear of losing control, not just of your life, but of the very fabric of existence.

### Welcome to Hobb's End, Please Leave Your Sanity at the Border

The arrival in Hobb's End is where the film truly sinks its claws in. Shot largely in the quaint, yet subtly unsettling, towns of Markham and Unionville, Ontario, the location becomes a character itself. Carpenter doesn't rely on jump scares; he builds atmosphere thick enough to choke on. The perpetually twilight-lit streets, the unnervingly vacant church (housing something decidedly unholy), the local populace behaving like distorted echoes from Cane's books – it all contributes to a mounting sense of dread. Remember the feeling of watching something truly wrong unfold on screen late at night? Hobb's End embodies that feeling.

Sam Neill is phenomenal as Trent. His journey from smug skeptic to terrified pawn is utterly convincing. You watch his carefully constructed reality crack, splinter, and ultimately shatter. There’s a weariness in his eyes early on that slowly morphs into wide-eyed horror, and finally, a terrifying form of acceptance. The supporting cast is equally effective, particularly Jürgen Prochnow's Cane, who appears sparingly but dominates his scenes with the quiet confidence of a god dictating his creation. His delivery of lines like "I think, therefore you are," lands with chilling weight.

### Practical Nightmares and Lovecraftian Whispers

This being a Carpenter film from the 90s, the practical effects, courtesy of KNB EFX Group, have that wonderfully tactile, disturbing quality we remember from the era. The grotesque transformations, the glimpses of creatures lurking just beyond perception – they feel viscerally real in a way CGI often struggles to replicate. The distorted figures shambling through the town, the infamous "wall of monsters," or Linda Styles's body contorting in ways that defy anatomy... these images burrow into your subconscious. Didn't those effects feel disturbingly tangible back then, even if they look a little dated now? There's a disturbing physicality to the horror that feels perfectly suited to the film's themes.

In the Mouth of Madness is arguably Carpenter's most overtly Lovecraftian film, though it cleverly avoids direct adaptation. The themes of ancient, cosmic entities influencing humanity, the insignificance of mankind, forbidden knowledge driving mortals insane – it's all pure H.P. Lovecraft filtered through Carpenter's lens. The film suggests Sutter Cane isn't merely writing fiction; he's channeling dictates from beings beyond comprehension, and his final book is the key to unlocking their return. It taps into that deep-seated fear that there are things in the universe we are simply not meant to understand.

### The Blue Fade and the Enduring Echo

Carpenter, collaborating again with composer Jim Lang, delivers a score that perfectly complements the visuals – a blend of rock-infused dread and synth-heavy atmospherics that underscores the escalating madness. The cinematography uses distinct blue filters in key moments, visually signaling shifts in reality or perception, adding another layer to the unsettling aesthetic.

Despite its brilliant concept and execution, In the Mouth of Madness sadly underperformed at the box office upon release (grossing roughly $10 million against an $8 million budget) and received somewhat mixed reviews. Critics weren't quite sure what to make of its bleak, meta-narrative. But like many Carpenter films, its reputation has only grown over time. It's now rightly regarded as a cult classic, a complex and chilling exploration of horror's power and the fragility of reality. It asks uncomfortable questions about the relationship between creator, creation, and audience, and offers no easy answers.

VHS Heaven Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's masterful atmosphere, Sam Neill's tour-de-force performance, its intelligent and terrifying Lovecraftian themes, and its enduring power to unsettle. It's a near-perfect execution of cosmic horror, held back only slightly by minor pacing dips in the middle. In the Mouth of Madness isn't just a movie you watch; it's an experience that lingers, making you question the shadows in the corner of your eye and perhaps glance nervously at your bookshelf. It remains one of Carpenter's most ambitious and intellectually frightening films, a chilling reminder that sometimes, the most terrifying monsters are the ones we read about... or perhaps, the ones reading us. Do you read Sutter Cane?