There's a certain kind of fog that rolls off some VHS tapes, isn't there? Not physical mould, but an atmospheric haze, a sense of something incomplete yet intensely potent. Watching Michael Mann's The Keep (1983) often feels like excavating such a tape – a film shrouded in its own troubled mythology, promising forbidden knowledge and delivering a fragmented, haunting dream. It doesn't just tell a story of ancient evil; it feels like an artifact unearthed, beautiful and broken.

### A Fortress of Shadows

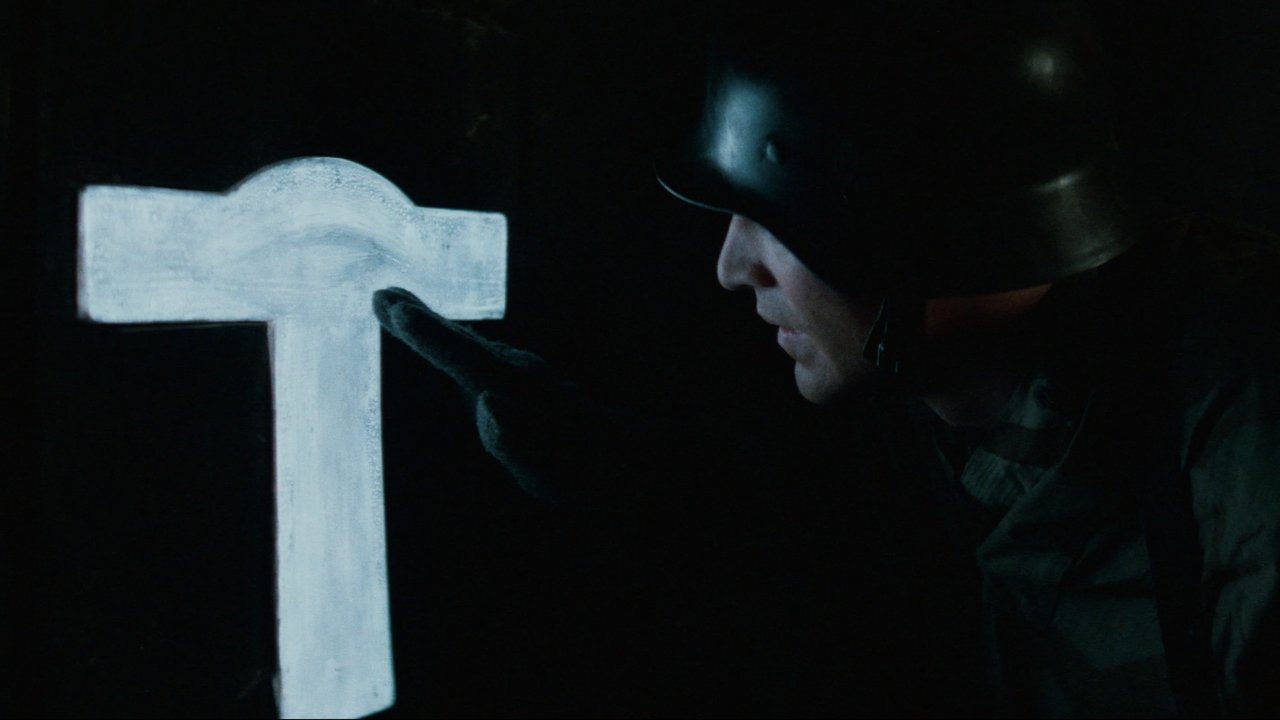

Forget your typical haunted house bumps in the night. The Keep plunges you into the oppressive gloom of the Dinu Pass in wartime Romania, where a detachment of German soldiers, led by the pragmatic Captain Woermann (Jürgen Prochnow, bringing a weary gravity soon after his iconic turn in Das Boot), makes the fatal error of occupying a monolithic, unsettling citadel. The design of the Keep itself is a masterclass in ominous architecture – impossible angles, light-swallowing obsidian blocks, and crosses embedded inward, suggesting containment rather than sanctity. From the outset, Mann, even this early in his career, demonstrates his unparalleled eye for visual mood, crafting a pervasive sense of dread long before anything explicitly supernatural occurs. The air hangs thick with unspoken history and palpable menace.

### The Sound of Awakening Dread

And then there's the score. Oh, that score. Tangerine Dream's hypnotic, pulsating electronic soundscape isn't just background music; it's the film's bloodstream, the thrumming heartbeat of the ancient entity stirring within the walls. Heard echoing from the speakers of a CRT television late at night, it possessed an otherworldly quality, simultaneously futuristic and archaic. It amplified the isolation, the encroaching darkness, and the sheer strangeness of what unfolds. Even today, it remains one of cinema's most distinctive and effective electronic scores, perfectly capturing the film's unique blend of historical grit and cosmic horror. Does any other soundtrack quite feel like the slow awakening of something vast and terrible?

### Fractured Fairy Tale, Wartime Horror

The plot, adapted by Mann from F. Paul Wilson's novel, sees the German soldiers inadvertently unleashing Molasar, an ancient, powerful being, as they tamper with the Keep's structure. Nightly deaths decimate the garrison, prompting the arrival of the ruthless SS Sturmbannführer Kaempffer (Gabriel Byrne, chillingly detached) and, eventually, a Jewish historian, Dr. Theodore Cuza (Ian McKellen, delivering a performance of fragile intensity), summoned to decipher the Keep's runic inscriptions. Cuza finds himself tempted by Molasar's power, offered as a means to fight the Nazis, while a mysterious, almost ethereal figure, Glaeken (Scott Glenn, embodying stoic enigma), journeys towards the Keep with his own ancient purpose.

This is where the film's infamous production battles cast long shadows. The Keep is notoriously a victim of studio interference and drastic cuts. Mann's original vision was reportedly over three hours long, a sprawling epic that delved deeper into the mythology, character motivations, and the complex relationship between Cuza and Molasar. Paramount, however, demanded a cut under 100 minutes, resulting in a narrative that often feels elliptical, characters whose arcs seem truncated, and plot points left dangling. The visual effects supervisor, Wally Veevers, tragically died during production, further complicating matters and leading to some compromises in the final look of Molasar, whose initial, more ambitious designs conceived by Nick Maley (known for his work on Yoda!) were reportedly scaled back.

### The Ghosts of Production

These behind-the-scenes struggles, costing an estimated $6 million back then (around $19 million today) and resulting in a disappointing box office return, are inseparable from the experience of watching The Keep. Knowing about the lost footage, the studio battles, and F. Paul Wilson's own vocal dissatisfaction with the adaptation adds another layer to its mystique. It becomes a cinematic puzzle box, inviting viewers to piece together the implied narrative, to imagine the film that might have been. The result is less a straightforward story and more a sequence of incredibly potent, atmospheric vignettes – the eerie glow emanating from the walls, the shocking disintegration of soldiers, the dreamlike confrontations. It's frustrating, yes, but also strangely compelling. Did Mann's relentless visual style somehow benefit from the narrative gaps, forcing us to rely purely on mood and imagery?

The practical effects, even when compromised, retain a certain chilling physicality characteristic of the era. Molasar, particularly in his initial smoky, energy-crackling form, feels genuinely menacing. The unsettling makeup on McKellen as Cuza is revitalized also carries a visceral impact. It’s a reminder of a time before CGI smoothness took over, when monsters felt tactile, present in the frame with the actors.

### Enduring Enigma

The Keep remains a fascinating outlier – part war film, part dark fairy tale, part existential horror, filtered through Michael Mann's burgeoning hyper-stylized lens. It doesn’t neatly fit any genre box. Its flaws are undeniable, born from a troubled creation, leaving narrative threads frayed and character arcs feeling incomplete. Yet, its strengths are equally powerful: the overwhelming atmosphere, the unforgettable score, the striking visuals, and strong performances grappling with ambitious ideas. It’s a film that lingers precisely because of its imperfections and the haunting sense of potential just beyond the frame. It’s a cult classic cherished not despite its flaws, but perhaps partly because of them – they contribute to its unique, dreamlike aura.

Rating: 7/10

Justification: The score loses points for its narrative incoherence and the clear signs of post-production butchery that leave frustrating gaps. However, the sheer power of its atmosphere, Michael Mann's stunning visual direction (even in nascent form), Tangerine Dream's iconic score, and memorable performances from McKellen, Prochnow, and Glenn elevate it significantly. It achieves a unique mood of dread and wonder that few films manage.

Final Thought: The Keep is the quintessential "what could have been" film of the VHS era. It's a beautiful, haunting enigma – a film whose missing pieces only deepen its dark allure, forever whispering secrets from that fog-shrouded fortress in the Dinu Pass.