Some films settle into the corners of your memory like dust motes caught in a sunbeam – quiet, persistent, and carrying a weight beyond their size. Alberto Lattuada's Stay As You Are (1978), or Così come sei as it was known in its native Italy, is one such film. Finding this on a flickering CRT screen, perhaps nestled in the ‘Foreign Drama’ section of a long-gone video rental store, felt like uncovering something hushed and potentially forbidden. It wasn't the explosive action or broad comedy that dominated the shelves; it was something altogether different, a film that whispered difficult questions rather than shouting easy answers.

An Encounter Across Time

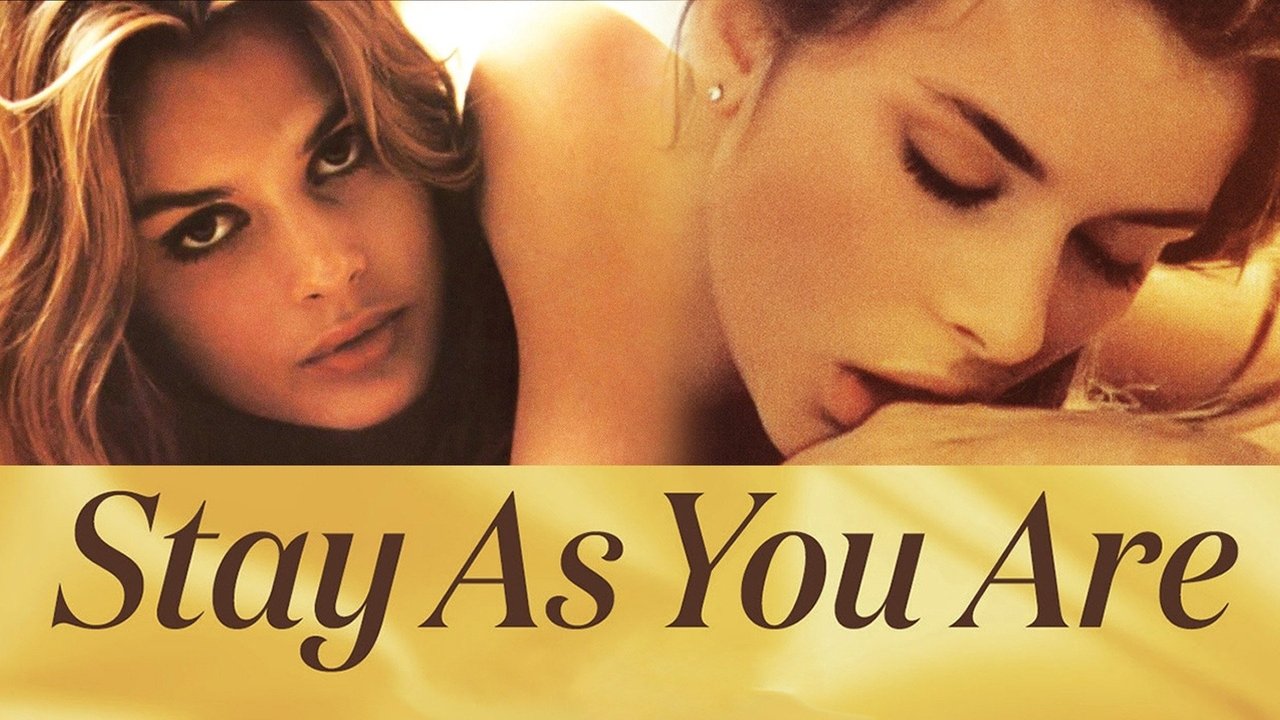

The premise is deceptively simple, yet instantly complex. Giulio Marengo, played by the eternally charismatic Marcello Mastroianni (already a titan thanks to collaborations with Federico Fellini like 8½ (1963)), is a middle-aged architect in Florence, comfortably numb in his routine and marriage. He meets Francesca, a young, free-spirited student portrayed with startling presence by a very young Nastassja Kinski. An affair ignites, fueled by Giulio's yearning for lost youth and Francesca's enigmatic allure. Florence, captured beautifully by Lattuada, isn't just a backdrop; it's a timeless witness to their clandestine meetings, its ancient beauty contrasting with the very modern anxieties unfolding within its streets.

The Unspoken Question

But Lattuada, working from a script he co-wrote, introduces a devastating complication early on. Giulio begins to suspect that Francesca might be his own daughter, conceived during a brief, forgotten encounter years before. This suspicion hangs heavy over every subsequent scene, transforming the May-December romance into something fraught with potential taboo. The film never explicitly confirms or denies this possibility, forcing the characters – and the audience – to grapple with the agonizing ambiguity. Does the possibility change the nature of their connection? Does ignorance offer any true absolution? It’s a question that gnaws at you long after the haunting notes of Ennio Morricone's score fade.

Navigating Difficult Terrain

The weight of the film rests heavily on its two leads, and they carry it masterfully. Mastroianni is superb as Giulio, embodying a man caught between desire and decorum, liberation and profound unease. You see the weariness in his eyes, the flicker of rejuvenation when he’s with Francesca, and the mounting panic as the central doubt consumes him. It's a performance layered with the complexities of middle-aged regret and confusion.

And then there's Nastassja Kinski. Barely 17 when filming began, she delivers a performance of astonishing maturity and raw magnetism. It’s a role that courted controversy, given her age and the film's subject matter, but Kinski imbues Francesca with a compelling mix of innocence, sensuality, and an almost unnerving self-awareness. She isn't merely a passive object of desire; she possesses her own agency, her own mysteries. Watching her here, it’s impossible not to see the spark of the international star she would soon become with acclaimed roles in films like Roman Polanski's Tess (1979) and later 80s staples such as Cat People (1982). The chemistry between her and Mastroianni is undeniable, yet it's perpetually underscored by that terrible, unspoken possibility, making their interactions both tender and deeply unsettling.

A Director's Delicate Hand

Alberto Lattuada, a veteran of Italian cinema known for exploring societal taboos and complex relationships, directs with a sensitive, observational style. He avoids overt moralizing, instead allowing the emotional turmoil to play out through subtle glances, lingering silences, and the characters' interactions with their environment. The pacing is deliberate, characteristic of European cinema of the era, demanding patience but rewarding it with emotional depth. It’s a film less concerned with plot mechanics than with the internal landscapes of its characters. It doesn't shy away from the sensuality inherent in the affair, but that sensuality is constantly complicated by the underlying dread. This wasn't your typical Hollywood fare, and discovering it on VHS felt like accessing a more adult, more challenging world of storytelling.

Reflections in the Static

Stay As You Are isn't an easy film. Its central ambiguity can be frustrating for those seeking neat resolutions. The subject matter remains deeply uncomfortable, prompting necessary reflection on power dynamics, consent, and the very nature of love and connection when shadowed by potential transgression. Yet, its power lies precisely in its refusal to simplify. It captures a specific kind of European cinematic sensibility – introspective, melancholic, and unafraid to explore the darker, more complex corners of human experience. It’s a film that lingers, not because of explosive moments, but because of the quiet intensity of its performances and the profound weight of the questions it dares to ask.

Rating: 7/10

This score reflects the film's strengths – primarily the compelling, brave performances from Mastroianni and a star-making turn from Kinski, Lattuada's sensitive direction, and its willingness to tackle profoundly uncomfortable themes with nuance rather than exploitation. It avoids a higher score due to the inherently unsettling nature of its premise, which will understandably be off-putting for some viewers, and a deliberately paced narrative that might test the patience of those accustomed to faster-moving plots. However, for those willing to engage with its challenging core, Stay As You Are offers a thoughtful, haunting cinematic experience that exemplifies a certain kind of daring European filmmaking rarely seen today.

It leaves you contemplating the fragile nature of identity and the devastating consequences of secrets, both kept and suspected. What truly defines our relationships, and can love exist untainted in the shadow of such profound doubt? The film offers no easy answers, leaving those questions echoing long after the tape finishes rewinding.