The clipped accents and cricket whites almost fool you. Almost. There's a veneer of tradition, of unchanging Englishness, coating the hallowed halls of the public school in Another Country (1984). But beneath the surface, something festers. It’s not just the adolescent angst typical of boarding school dramas; it’s a disillusionment so profound, it threatens to crack the very foundations of King and Country. Watching it again now, decades removed from its mid-80s release, the film feels less like a period piece and more like a chillingly prescient exploration of how systems breed their own destruction.

Beyond the Playing Fields

Based on Julian Mitchell's own successful stage play (which he adapted for the screen), the story, set in the 1930s, orbits around Guy Bennett (Rupert Everett), an openly gay and flamboyantly witty student aiming for a prestigious position within the school hierarchy. His best friend, Tommy Judd (Colin Firth), is a committed Marxist, openly despising the oppressive class system they inhabit. When a scandal involving another student erupts, the school's rigid authorities clamp down, and the subtle hypocrisies and brutal prejudices simmering beneath the polite facade boil over, setting Bennett on a path that the film subtly implies leads to espionage against the nation that ostracized him.

It's fascinating to think this film, steeped in pre-WWII tensions, arrived on VHS shelves during the height of the Cold War and Thatcher's Britain. The parallels weren't accidental. The story itself was loosely inspired by the life of Guy Burgess, a member of the infamous Cambridge Five spy ring who defected to the Soviet Union. Another Country isn't just about schoolboy concerns; it's a sharp critique of an establishment that demands conformity while nurturing the very resentments that lead to betrayal. What does loyalty mean, the film asks, when the system you're expected to be loyal to fundamentally rejects who you are?

Birth of Stars, Capture of Truth

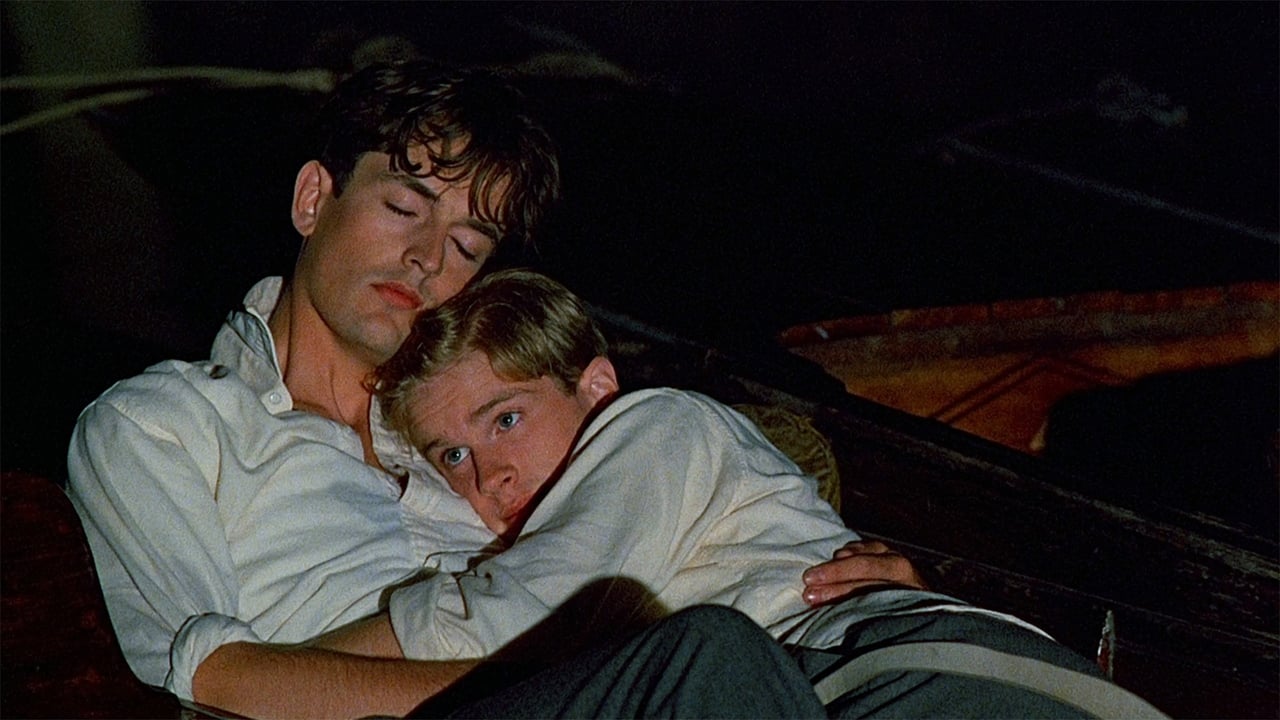

You simply cannot discuss Another Country without focusing on the incandescent performances of its young leads, captured here at the very cusp of their careers. Rupert Everett is Guy Bennett. Having originated the role on the London stage, he embodies Bennett's vulnerability, his acidic wit, and his yearning for acceptance with an electrifying presence. It’s a performance brimming with charisma and defiance, but also laced with a palpable pain that makes his eventual implied choices feel tragically inevitable. Everett's Bennett isn't just rebellious; he's wounded, and that wound is inflicted by the very institution he initially aspires to conquer.

Equally compelling, though in a starkly different key, is Colin Firth as Tommy Judd. Interestingly, Firth had played Bennett on stage after Everett, but here takes on the role of the quiet, fiercely intellectual Marxist. Firth portrays Judd's idealism and his simmering outrage with a remarkable stillness and conviction. His scenes with Everett crackle with the energy of opposites attracting – the flamboyant aesthete and the austere ideologue finding common ground in their shared outsider status. Their friendship feels authentic, a small pocket of sincerity in a world built on artifice. And look closely – you'll spot a very young Cary Elwes (just a few years before The Princess Bride) in one of his earliest roles as Bennett's sympathetic classmate, James Harcourt. For fans tracking careers, watching Everett and Firth here, so young and already so commanding, is a genuine thrill – a snapshot of future screen legends finding their footing.

Crafting the Gilded Cage

Director Marek Kanievska (who earned a nomination for the Palme d'Or at Cannes for the film) masterfully uses the picturesque setting – filmed largely at Oxford University locations like Brasenose College and the Bodleian Library, doubling for the fictional school – not just as a backdrop, but as a character in itself. The stunning architecture and manicured grounds feel less inviting and more like a beautiful prison. The cinematography often frames the boys against imposing structures or through restrictive doorways, visually reinforcing the confining nature of their world. There's a deliberate, almost suffocating quality to the atmosphere, punctuated by moments of Bennett's performative rebellion.

Julian Mitchell's script retains the sharp intelligence and biting dialogue of his play. It peels back the layers of propriety to expose the fear, ambition, and prejudice underneath. There are no easy answers here, no simple heroes or villains. Even the authority figures, seemingly monolithic in their adherence to tradition, are shown to be complex, sometimes conflicted individuals navigating a system they are sworn to uphold.

Echoes in the Hallways

Another Country wasn't a massive blockbuster, certainly not the kind of film that dominated every shelf at Blockbuster back in the day. You might have had to hunt for it, perhaps drawn in by the striking cover art or a recommendation from a clerk who knew their stuff. Finding it felt like uncovering something significant, a thoughtful and provocative piece of cinema that stood apart from the era's more bombastic offerings.

Its power lies in its refusal to offer easy resolutions. It presents a crucible where personal identity, political ideology, and societal pressure collide, forcing characters to make choices with devastating consequences. It’s a film that probes the roots of dissent, suggesting that sometimes, the greatest betrayals are born not from malice, but from the pain of exclusion. Doesn't that tension, between belonging and staying true to oneself, still resonate deeply today?

Rating: 9/10

This is a near-perfect rendering of its source material, elevated by career-defining early performances and intelligent direction. Thematically rich, beautifully shot, and superbly acted, Another Country captures a specific moment in history while asking universal questions about loyalty, identity, and the corrosive effects of hypocrisy. It justifies its high rating through its enduring power to provoke thought and its showcase of nascent talent burning incredibly bright.

It lingers long after the credits roll – a haunting portrait of youthful idealism curdling into something far more dangerous, all within the suffocating beauty of England's dreaming spires. A must-watch for anyone interested in stellar British drama and the early work of screen icons.