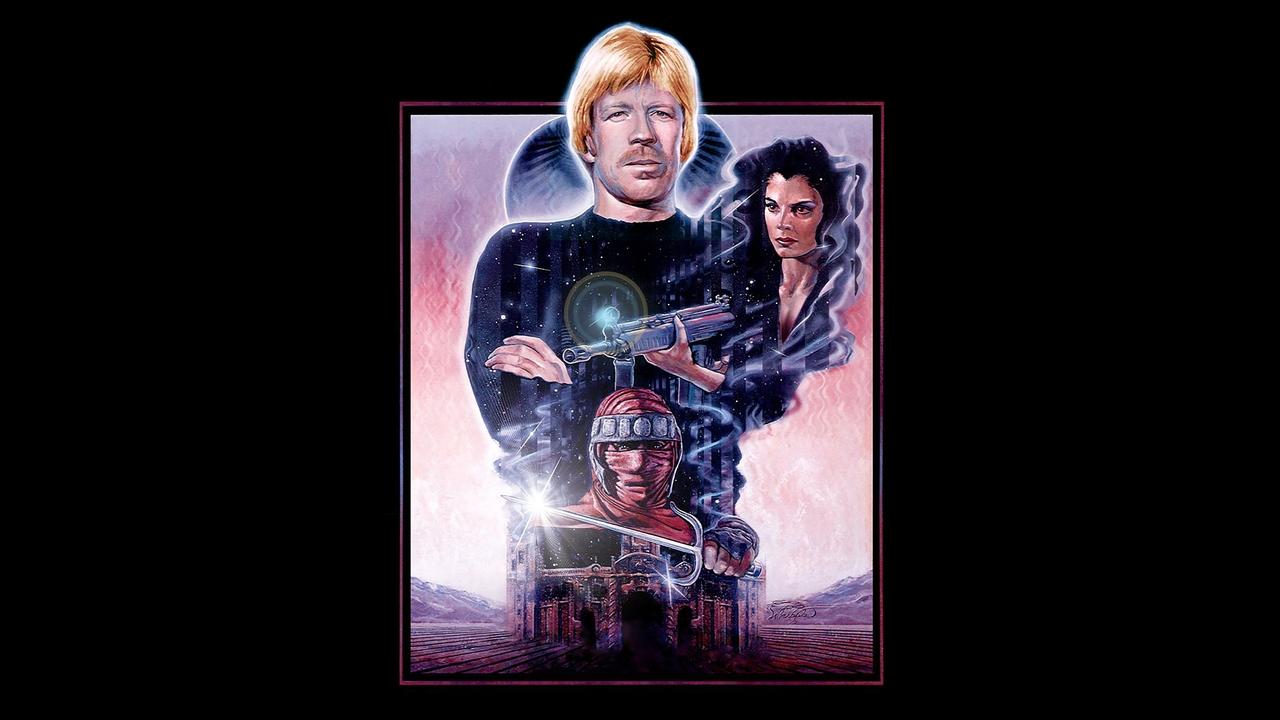

Alright, pop that tape in the VCR, adjust the tracking just so, and let's talk about a film that practically defines early 80s action cheese, albeit with a deadly serious face: 1980's Chuck Norris head-kick extravaganza, The Octagon. If you haunted the action aisles of your local video store, chances are this cover art – Norris looking stoic, maybe some shadowy ninja figures lurking – practically jumped off the shelf. Forget slick, modern spy thrillers; this was raw, slightly clumsy, but undeniably earnest stuff.

And let's get it out of the way immediately: the whisper. That whisper. You know the one. Scott James's (Norris) internal monologue, bizarrely rendered as this echoing, almost ethereal voiceover that permeated the entire film. It’s the kind of stylistic choice that screams "early 80s sound mixing experiment," and legend has it (Retro Fun Fact incoming!) that this infamous echo effect was added in post-production, much to Norris's own surprise and alleged chagrin. Love it or hate it (and oh boy, did audiences have opinions!), it's become the film's most unintentionally iconic feature, a strange audio fingerprint you just can't forget.

### Ninjas, Ninjas Everywhere!

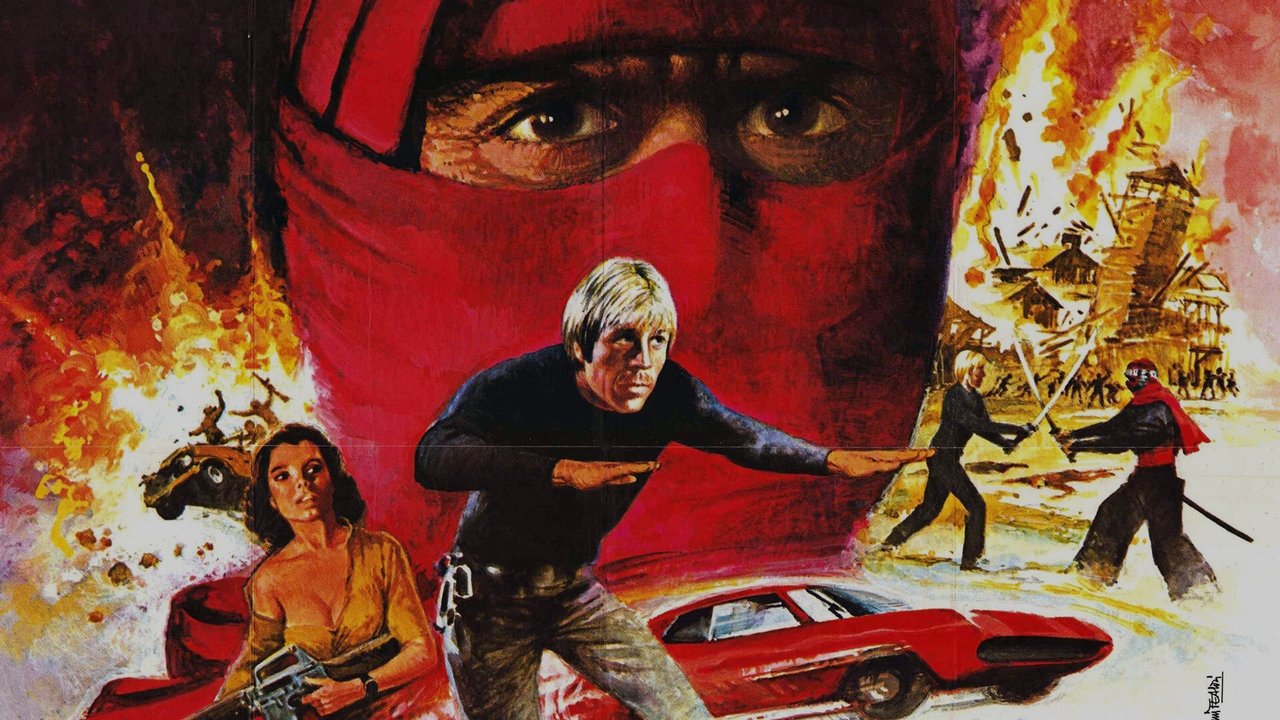

The plot, frankly, is wonderfully straightforward in that classic action movie way. Chuck Norris plays Scott James, a retired martial arts champion haunted by memories of rigorous, borderline abusive ninja training alongside his foster brother, Seikura (played by real-life karate master Tadashi Yamashita). When a wealthy heiress, Justine (Karen Carlson), finds herself targeted by shadowy assassins employing deadly ninja techniques, she seeks out Scott for help. Turns out, these aren't just any ninjas; they're part of a global terrorist training network operating from a hidden fortress complex – the titular Octagon – run by none other than Scott’s estranged, power-mad brother. Cue the reluctant hero trope, inner turmoil (amplified by those whispers!), and the inevitable path towards a high-kicking showdown.

What really sells The Octagon, especially watching it now through a nostalgic lens, is its absolute commitment to the burgeoning ninja craze of the era. This film hit just as ninjas were becoming the cool, mysterious movie bad guys. Director Eric Karson (who later gave us another slice of 80s action with Black Eagle) leans into the mystique, showcasing hidden training camps, silent assassins scaling walls, and plenty of shuriken-throwing mayhem. It feels less like the polished, wire-fu spectacles we'd see later and more like something grounded, albeit dramatically heightened.

### Practical Kicks and Gritty Hits

Let’s talk action, because that’s the main event here. Forget CGI pixel-storms; The Octagon delivers its thrills the old-fashioned way. When Norris throws a roundhouse kick, you feel the impact, even through the slightly grainy VHS transfer. The fight choreography, often coordinated by Chuck's own brother, Aaron Norris (a frequent collaborator and stuntman extraordinaire), has that satisfyingly crunchy, practical feel. Remember how real those bullet hits sometimes looked back then, often achieved with squibs? There's a similar rawness here. Stunt performers are clearly taking real tumbles, crashing through actual (or balsa wood) structures, and engaging in elaborate, if sometimes slightly slow-motion, hand-to-hand combat.

There’s a sequence where Scott infiltrates one of the ninja training camps that perfectly encapsulates this. It's tense, relying on stealth and Norris's physical prowess rather than digital trickery. Sure, some of the sets might look a bit... well, economical (the film was made for a modest $4 million, though it pulled in a respectable $19 million at the box office – a solid hit!), but the dedication to practical stunts and martial arts showcases is undeniable. It felt dangerous in a way that hyper-edited, digitally smoothed modern action sometimes struggles to replicate.

### Icons in the Mix

While Norris carries the film with his trademark stoicism and impressive physical skills (this was peak, pre-Walker, Texas Ranger Norris), the supporting cast adds some welcome flavor. Karen Carlson does her best as the damsel in distress who eventually shows some grit. But the real standout is the legendary Lee Van Cleef as McCarn, a grizzled anti-terrorist operative who essentially runs a mercenary group dedicated to hunting down the ninja menace. Fresh off decades of iconic spaghetti western roles like The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966), Van Cleef brings an effortless cool and steely-eyed intensity that elevates every scene he's in. His presence lends the film a weight it might otherwise lack, bridging the gap between classic genre filmmaking and the new wave of 80s action.

### The Verdict on the VHS Copy

Watching The Octagon today is like finding a beloved, slightly worn-out cassette in the back of the closet. It’s undeniably dated in places – the pacing can drag, the dialogue occasionally clunky, and that whisper... well, it's still baffling. Yet, there’s an undeniable charm to its straightforward narrative and commitment to practical action. It captures a specific moment in time when ninja movies were king and Chuck Norris was solidifying his place as a bankable action hero. Critics at the time weren't overly kind, but audiences seeking straightforward thrills made it a video rental mainstay. It’s a movie that knew exactly what it wanted to be: a vehicle for Norris to kick bad guys, wrapped in the trendy mystique of ninjutsu.

Rating: 6/10

Justification: The film earns points for its earnest practical action, Norris's martial arts prowess, Lee Van Cleef's fantastic presence, and its status as a key entry in the early 80s ninja craze. It loses points for the sometimes sluggish pacing, dated production values, occasionally awkward dialogue, and, yes, that divisive internal monologue echo. It's flawed, but its nostalgic appeal and significance within its niche genre make it a worthwhile watch for retro fans.

Final Thought: The Octagon might be a bit creaky around the edges, but fire it up for a dose of pure, unadulterated 80s action where the kicks felt real, the ninjas were plentiful, and sometimes, your own thoughts echoed back at you. Just try not to whisper along.