## Sun-Drenched Decay and the Ghost at the Feast

There's a particular kind of emptiness that permeates Less Than Zero (1987), one that clings long after the tape hiss fades and the VCR clicks off. It’s not just the vacant stares or the casual cruelty flickering across the screen; it’s baked into the very fabric of the film’s Los Angeles – a landscape of blinding sunshine, opulent mansions, and aching, cavernous loneliness. I remember renting this one, perhaps drawn by the familiar faces of Andrew McCarthy and Jami Gertz, expecting maybe a slightly edgier John Hughes affair. What unfolded instead was something far more unsettling, a postcard from the edge that felt less like a cautionary tale and more like a dispatch from a battlefield where the casualties were already mounting.

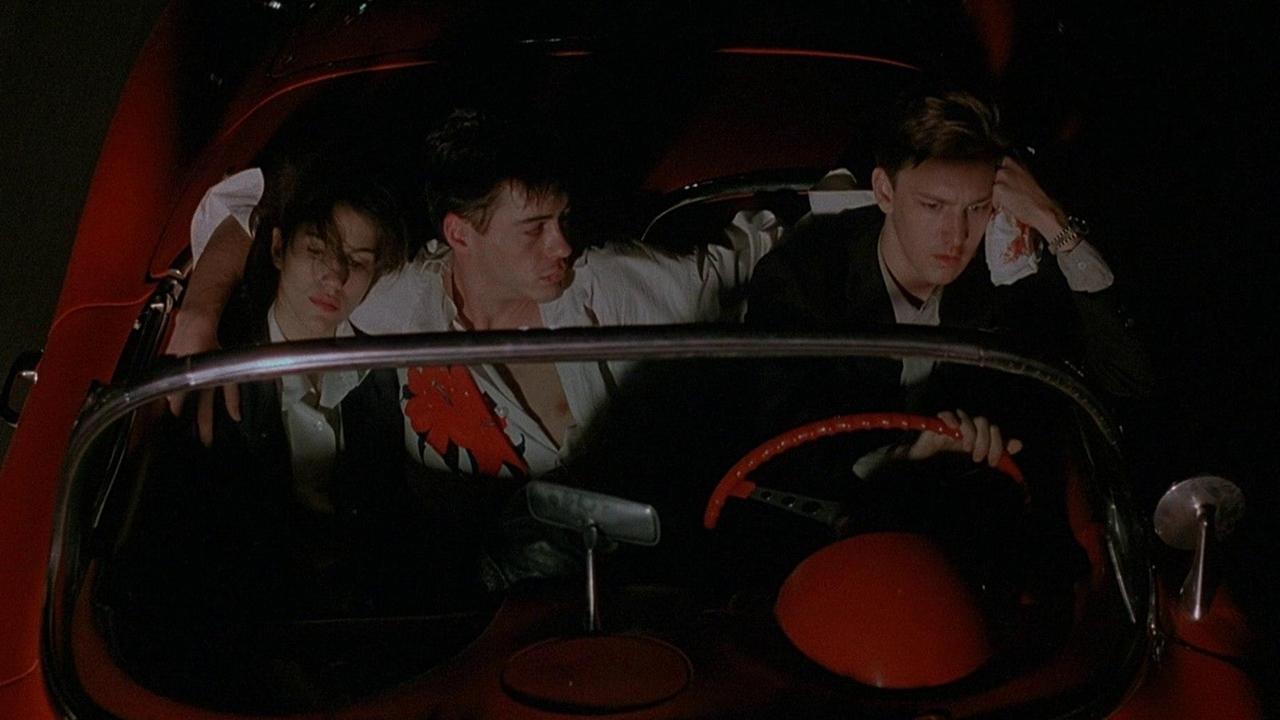

Based, albeit loosely, on the controversial debut novel by Bret Easton Ellis, the film follows Clay (McCarthy) as he returns home from college for Christmas break. He finds his hometown world – and his former best friend Julian (Robert Downey Jr.) and ex-girlfriend Blair (Jami Gertz) – irrevocably changed, caught in a downward spiral of cocaine, debt, and profound disconnection. Director Marek Kanievska, who had previously helmed the stylish British crime film Another Country (1984), captures this milieu with a slick, almost detached eye. The parties are lavish, the clothes are aggressively '80s, but there's a hollowness beneath the gloss, a sense that everything vibrant has already curdled.

Ghosts in the Machine

While McCarthy serves as our reserved, increasingly horrified observer, and Gertz effectively portrays Blair's conflicted loyalties and weary complicity, the film truly belongs to Robert Downey Jr. His portrayal of Julian Wells is nothing short of devastating. It's a performance stripped bare of vanity, radiating a desperate, frantic energy that masks an utterly broken spirit. This wasn't the charming rogue Downey Jr. would later perfect; this was raw, exposed nerve. Watching it again now, knowing the actor's own subsequent struggles, lends the performance an almost unbearable poignancy. There's a scene where Julian, high and cornered, pleads with Clay – the flicker of the lost boy beneath the addict's ravaged facade is heart-wrenching. It’s a performance that transcends the screen; it feels terrifyingly real. Why did it resonate so deeply? Perhaps because it refused easy answers or sentimental escapes, presenting addiction not as a plot device, but as a consuming void.

The film famously diverges quite significantly from Ellis's much bleaker, more nihilistic novel. Screenwriter Harley Peyton (who would later work on Twin Peaks) introduces a more conventional narrative arc, particularly a rescue plot that Ellis’s book pointedly avoided. Ellis himself wasn't thrilled with the adaptation, feeling it softened the edges too much. It’s true, the film pulls back from the novel’s explicit extremity and pervasive amorality. Yet, in doing so, it arguably makes the tragedy more accessible, focusing the emotional core on the shattered friendship and the desperate attempts to pull Julian back from the brink. This shift might explain its modest box office return (around $12.4 million from an $8 million budget) compared to more upbeat youth films of the era; it offered discomfort instead of catharsis.

The Sound of Silence

Beyond the performances, the film’s atmosphere is powerfully amplified by its soundtrack. It's an iconic 80s compilation, featuring everything from The Bangles’ haunting cover of "Hazy Shade of Winter" (which became a huge hit thanks to the film) to LL Cool J and Run-DMC. But unlike the celebratory soundtracks of other teen movies, here the music often feels like another layer of insulation, the pulsing beat drowning out the whispers of despair. The visual style, courtesy of cinematographer Edward Lachman (later known for his work with Todd Haynes), further enhances this dichotomy – bright, saturated colours that somehow feel cold, capturing the artificiality of the world these characters inhabit. Remember those stark white interiors and neon-lit clubs? They felt less like spaces for connection and more like expensive waiting rooms for the inevitable crash.

Weaving in a bit of trivia, it's fascinating that McCarthy, often cast as the sensitive romantic lead in films like Pretty in Pink (1986), takes on the more passive, observational role here, allowing Downey Jr.'s tragic energy to dominate. It was a subtle subversion of the "Brat Pack" archetypes many viewers likely expected walking into the theater or pressing play on that worn-out rental tape. The locations themselves – those sprawling Beverly Hills homes and shadowy L.A. underpasses – become characters, reflecting the stark divide between surface wealth and hidden decay.

Lingering Shadows

Less Than Zero isn't a feel-good movie, nor is it a simple morality play. It’s a snapshot of a specific kind of affluent ennui and the devastating consequences of unchecked excess, anchored by a performance that remains incredibly powerful and deeply troubling. It captures a dark undercurrent of the 80s often glossed over in nostalgic recollections. Does the narrative simplification compared to the novel weaken it? Perhaps for purists. But the emotional core, particularly Julian's plight as portrayed by Downey Jr., is undeniable. It asks uncomfortable questions about responsibility, friendship, and the point at which you can no longer save someone from themselves.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's haunting atmosphere, its stylish direction, and, above all, Robert Downey Jr.'s seismic performance. While the plot deviates significantly from the source material, sometimes feeling a touch conventional in its structure compared to the novel's raw edge, the film succeeds profoundly as a mood piece and a showcase for an actor giving his absolute all. It’s a film that doesn’t offer easy comfort, leaving instead a lingering chill and the echo of desperate voices lost in the California sun. What stays with you most isn't the plot, but the feeling – that specific, hollow ache of watching beautiful things decay.