Okay, fellow travellers on the magnetic tape highway, let's talk about a film that likely never graced the "New Releases" wall at your local Video Palace, but represents a fascinating, almost alien transmission from the outer limits of 80s cinema. Forget car chases and synth scores for a moment; we're venturing into the fiercely personal, hand-crafted universe of Stan Brakhage with his 1987 work, The Dante Quartet. This isn't a movie in the way we usually think of one, not a story told with actors and dialogue, but something else entirely – a visual scream, a torrent of colour and texture painted directly onto the very celluloid that carries it.

### A Universe Painted on Film

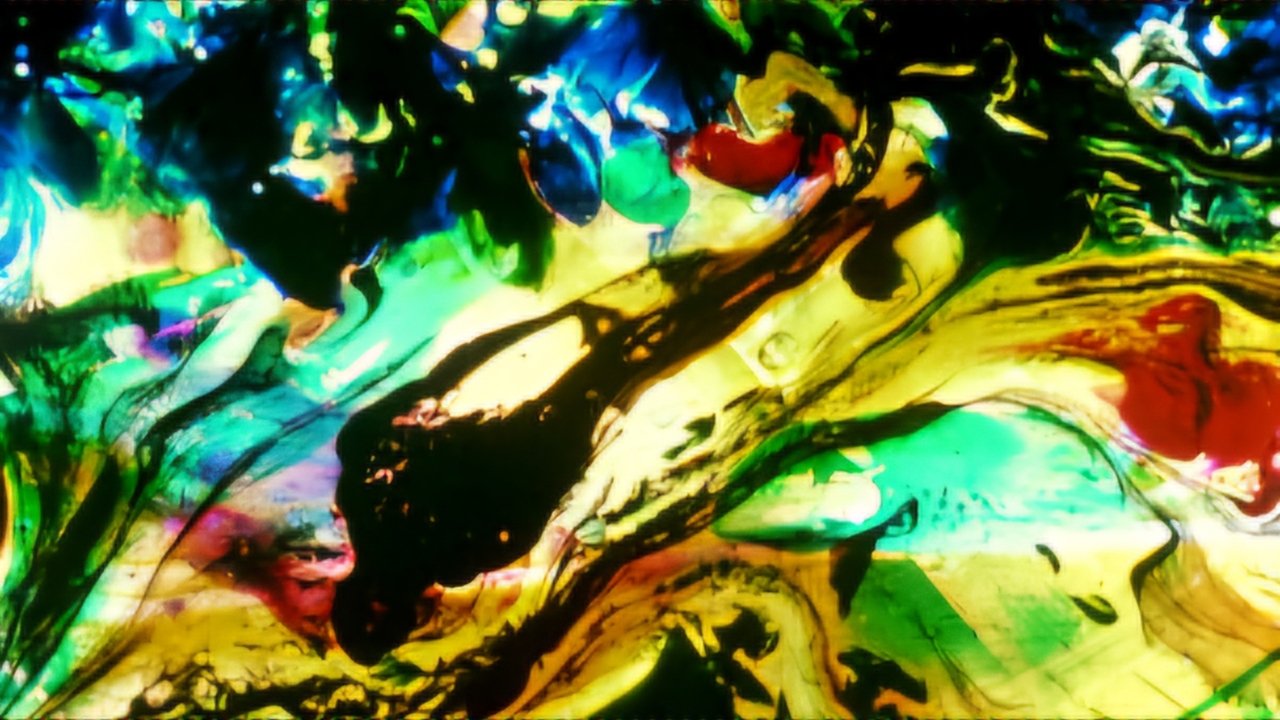

What confronts you when The Dante Quartet begins? It's an explosion. Six minutes – that's all it is – of frenetic, abstract imagery. Brakhage, a titan of American avant-garde filmmaking, sought to condense Dante Alighieri's epic journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise (The Divine Comedy) into a purely visual, non-narrative experience. There are no guiding captions, no narration, just the relentless flow of painted, scratched, and manipulated film frames. Watching it feels less like viewing a movie and more like having pure sensation beamed directly into your optic nerve. It’s overwhelming, disorienting, and utterly unlike anything else.

### The Artist's Hand

The real "behind-the-scenes" story here isn't about diva actors or troubled productions in the conventional sense. It's about the sheer, mind-boggling labor involved. Brakhage worked directly onto the film stock – initially 8mm, then blown up, but primarily working directly on 35mm for works like this later in his career. He wasn't animating frame-by-frame in the traditional way; he was applying paint, dye, ink, even dust or moth wings sometimes, directly onto the filmstrip, often using techniques that involved layering, scratching, and physically altering the emulsion. Think about that for a second. Every single one of the thousands of frames in these six minutes was individually touched, marked, and infused with his energy. It’s an act of intense physical and artistic commitment, a stark contrast to the increasingly slick, computer-aided visuals starting to emerge elsewhere in the late 80s. This feels primal, ancient almost, despite its relatively recent creation. He reportedly spent years crafting these six minutes, treating the filmstrip like a canvas.

### Not Your Usual Friday Night Rental

Let's be honest, the chances of finding The Dante Quartet nestled between Lethal Weapon (1987) and Dirty Dancing (1987) at the video store were practically zero. This was the kind of film you might have stumbled upon in a university film society screening, projected onto a slightly stained screen in a hushed room, or perhaps encountered years later through dedicated compilations sought out by the truly adventurous cinephile. It didn’t have taglines or trailers in the conventional sense. Its circulation was within a different ecosystem entirely – the art galleries, museums, and dedicated circles of experimental film appreciation. Yet, its existence speaks to the sheer diversity of what was being committed to film during that era, far beyond the multiplex mainstream. Doesn't it make you wonder what other strange cinematic jewels were being forged, largely unseen by the masses glued to their VCRs?

### What Does It All Mean?

That's the million-dollar question, isn't it? The Dante Quartet resists easy interpretation. Is it a successful translation of Dante's complex theological and poetic vision? Probably not in any literal sense. Instead, it feels more like Brakhage grappling with the feeling of those realms – the chaotic, fiery torment of the Inferno, the striving ascent of Purgatorio, the transcendent, almost blinding light of Paradiso. It forces you, the viewer, to abandon narrative expectations and engage on a purely sensory level. What associations do these colours evoke? What rhythm do you perceive in the frantic editing? It bypasses the analytical mind and aims straight for the gut, or perhaps the soul. It asks us to consider what film can be when stripped bare of story and character, reduced to its most fundamental elements: light, colour, time.

The experience is demanding, even taxing. It's certainly not "entertainment" in the way we typically use the word. But the sheer commitment to vision, the raw, handmade quality, and the audacious attempt to capture something so immense in such a condensed, abstract form leaves a distinct mark. It’s a reminder that even within the familiar landscape of 80s film, there were artists pushing the boundaries in ways that still feel radical today.

Rating: 7/10

Justification: This rating reflects the film's undeniable artistic significance, its breathtakingly unique handcrafted technique, and its bold ambition within the avant-garde tradition. Stan Brakhage achieved something technically and conceptually remarkable. However, its extreme abstraction and deliberate rejection of narrative make it inaccessible and potentially alienating for a broad audience, even within the retro film community. It’s a challenging piece that commands respect for its artistry rather than easy enjoyment. Its value lies in its boundary-pushing nature and the sheer force of its visual intensity, earning it a high mark for uniqueness and craft, tempered slightly by its inherent lack of conventional accessibility.

Final Thought: The Dante Quartet might not be the tape you'd pop in for a casual movie night, but its existence is a potent reminder of the raw, untamed creative energies pulsing through the film medium in the 80s, far away from the Hollywood spotlight. It’s a celluloid fever dream, a testament to what happens when an artist takes the very substance of film into their own hands.