It begins in shadow, cramped and suffocating. A disembodied hand flops onto the bare floor, fingers twitching with nascent life. Soon, another joins it, then feet, dragging themselves across the confined space. A tongue slithers blindly, seeking a mouth. This isn't a nightmare fragment; it's the opening salvo of Jan Švankmajer's 1989 masterpiece of unease, Darkness, Light, Darkness (original Czech title: Tma, světlo, tma), a film less watched than felt, crawling under your skin and staying there. Forget jump scares; this is the deep, existential dread of inanimate matter yearning for wholeness, a feeling perfectly suited to the grainy intimacy of a well-worn VHS tape viewed in the dead of night.

Assembly Required, Sanity Optional

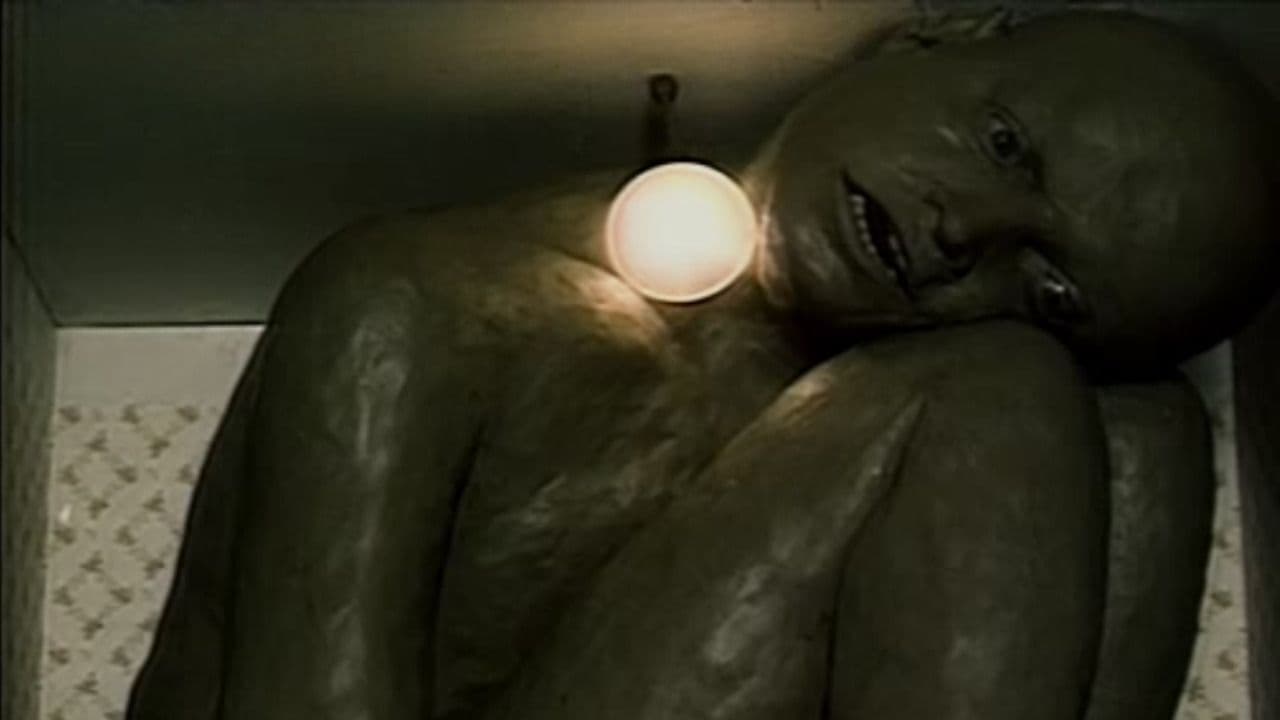

The premise is terrifyingly simple: disparate clay body parts – eyes, ears, teeth, organs – converge within a small, claustrophobic room. Driven by an unseen imperative, they begin the gruesome, clumsy process of assembling themselves into a complete human form. The genius of Švankmajer, a legendary figure in Czech surrealism and stop-motion animation, lies in making this grotesque construction utterly compelling. Each squelch, each slap of wet clay, each desperate scrabble for connection is rendered with a tactile reality that’s both fascinating and repulsive. There’s a palpable sense of struggle, of biological imperative stripped bare. Doesn't the sheer wrongness of that autonomously questing tongue still send a shiver down your spine?

Švankmajer wasn't just animating clay; he was breathing a disturbing semblance of life into it. His work, deeply influenced by the Surrealist movement he remained fiercely committed to throughout his career (even when banned from filmmaking by Czechoslovak authorities in the 70s), often explores the tension between the organic and the artificial, the conscious and the subconscious. Darkness, Light, Darkness feels like a primal scream from that subconscious space. The sound design is crucial here – not a score, but a symphony of visceral, wet, organic noises that make the animation feel disturbingly physical. You can almost feel the damp clay, the awkward friction of parts trying to fit.

The Unseen Hand of the Creator

Watching Švankmajer's work always prompts wonder about the process. Imagine the patience required, the frame-by-frame manipulation of these crude yet expressive forms. His studio wasn't a sterile digital environment; it was reportedly a cabinet of curiosities, filled with the objects and textures that populate his films. This hands-on, almost alchemical approach gives his animation a weight and presence that digital techniques often lack. There's a rumor, perhaps apocryphal but fitting, that Švankmajer preferred to work in near isolation, immersing himself fully in the strange worlds he birthed. This dedication pays off in the sheer, unadulterated vision present in every frame. It’s a style that would heavily influence filmmakers like Terry Gilliam and Tim Burton, as well as fellow stop-motion artists like the Brothers Quay.

The film's mere seven-minute runtime packs an incredible punch. As the body gradually takes shape, the sense of claustrophobia intensifies. The limbs bang against the walls, the head presses against the ceiling. The final, horrifying realization dawns: the completed man is now utterly trapped within the very room that allowed his formation. It's a potent, darkly funny, and deeply unsettling metaphor. Is it about the constraints of the physical body? The oppressive nature of societal structures (a reading often applied to art from behind the Iron Curtain)? Or simply the inherent absurdity and terror of existence? Švankmajer rarely offered easy answers, letting the disturbing imagery speak for itself.

Legacy in Clay and Shadow

Darkness, Light, Darkness wasn't some obscure oddity gathering dust. It won the Golden Bear for Best Short Film at the 40th Berlin International Film Festival, cementing Švankmajer's status as a master animator on the world stage. For those of us encountering it perhaps on a late-night arts program or a treasured compilation tape, it was unforgettable. It was the kind of filmmaking that expanded your understanding of what animation could be – not just cartoons, but potent, disturbing art. It didn’t offer comfort or easy resolution, just a lingering image of self-creation leading to self-imprisonment.

This short film remains a powerful example of stop-motion's unique ability to disturb and provoke thought. It’s a visceral, tactile experience that bypasses intellectual analysis to hit you squarely in the gut. The crude clay forms somehow convey more raw emotion and existential dread than many live-action features.

VHS Heaven Rating: 9/10

The score reflects the film's near-perfect execution of its unsettling vision, its technical mastery within the stop-motion medium, and its lasting power to disturb and fascinate. It loses a single point only because its extreme brevity and avant-garde nature might leave some viewers bewildered rather than chilled, though its impact is undeniable. Darkness, Light, Darkness is a chilling reminder from the analogue age that the most profound horrors can be sculpted from the simplest materials, leaving an indelible mark long after the screen fades to black. It’s pure, undiluted Švankmajer, and essential viewing for anyone interested in the darker, stranger corners of animation history.