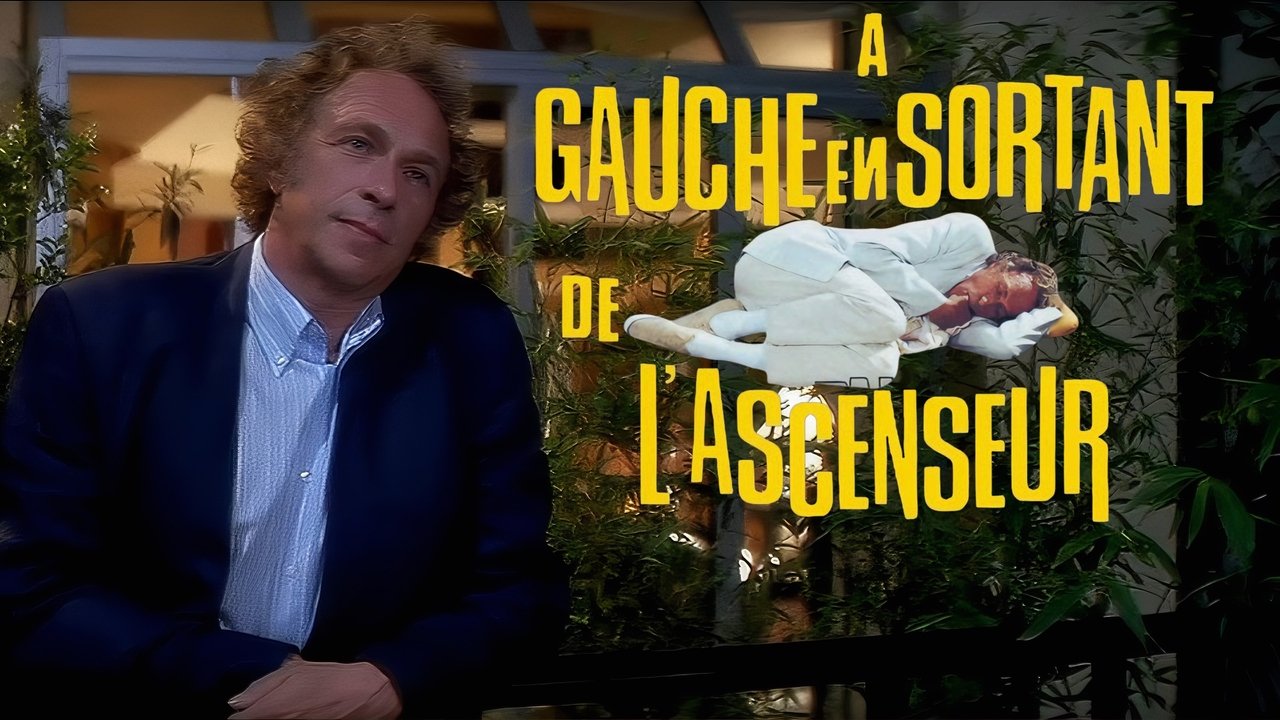

Ah, the French farce. It’s a delicate ecosystem, really – a finely tuned machine of slamming doors, escalating misunderstandings, and characters operating under exquisitely flawed logic. Get one element wrong, tip the balance too far, and the whole thing collapses into strained chaos. But when it works? It sings. And finding a gem like 1988’s Door on the Left as You Leave the Elevator (original title: À gauche en sortant de l'ascenseur) on a dusty VHS shelf back in the day felt like uncovering a slightly manic, utterly charming secret. It wasn't your typical booming Hollywood comedy; it had that distinct European rhythm, a controlled frenzy built on character and situation rather than just punchlines.

The Perfect Storm in Apartment 6B

The premise, adapted by Gérard Lauzier from his own stage play, is beautifully simple, almost claustrophobic. We’re largely confined to two adjacent apartments and the connecting landing. Yan (Pierre Richard), a timid, perpetually flustered graphic artist, is hopelessly in love with his married neighbour, Florence (Fanny Cottençon). His chance finally arrives when her husband is away. Simultaneously, across the hall, hyper-jealous painter Boris (Richard Bohringer) is having a volcanic argument with his stunning, much younger wife, Eva (Emmanuelle Béart). In a fit of pique, Boris destroys Eva's keys and locks her out... clad only in a revealing négligée. Seeking refuge, she ducks into the nearest open door – Yan's – just as Florence is arriving for their long-awaited rendezvous. Cue the elevator doors closing, locking mechanisms clicking, and the intricate gears of farce beginning to turn.

Clockwork Chaos Directed with Precision

What makes this film tick so effectively is the masterful hand of director Édouard Molinaro. Already renowned internationally for the sublime La Cage aux Folles (1978), Molinaro understands the essential mechanics of farce: confinement, timing, and escalating stakes. He keeps the action largely contained within the apartment building, heightening the pressure-cooker atmosphere. The camera work is often deceptively simple, letting the performers and the increasingly tangled situation drive the comedy. There’s a theatricality to it, naturally, given its stage origins, but Molinaro translates it into cinematic language brilliantly. You can almost feel the director meticulously blocking out the movements, ensuring each near-miss, each overheard snippet of conversation, lands with maximum comedic impact. It's less about flashy technique and more about invisible craft – the kind that makes controlled chaos look effortless.

A Trio of Comedic Firepower

The film rests squarely on the shoulders of its central trio, and they are magnificent. Pierre Richard, the reigning king of French comedic awkwardness, is in his element as Yan. His particular genius lies in physical comedy born of pure anxiety – the nervous tics, the frantic attempts at explanation that only dig him deeper, the sheer panic radiating from his eyes. He’s a human catastrophe magnet, and it’s impossible not to sympathise even as you laugh at his self-inflicted torment. Watching him try to hide the near-naked Eva while simultaneously wooing Florence is a masterclass in controlled panic.

Then there’s Richard Bohringer as Boris. If Richard is simmering anxiety, Bohringer is a barely contained volcano. His jealousy isn't just a character trait; it's a force of nature threatening to demolish the entire apartment building. The sheer intensity he brings to the role is hilarious precisely because it’s played so straight. He’s not winking at the audience; he is this terrifyingly insecure, possessive man, and his rage provides the perfect counterpoint to Richard's flailing.

And caught between them is Emmanuelle Béart as Eva. Often associated with more dramatic roles, even early in her career (she was just coming off the huge success of Manon des Sources (1986)), Béart proves adept at comedy here. She plays Eva not just as a damsel in distress, but as someone increasingly exasperated and resourceful within the absurdity swirling around her. Her natural screen presence adds a layer of glamour that makes the frantic situation even funnier. She’s the beautiful pawn in a game of escalating masculine idiocy.

Retro Fun Facts: Behind the Locked Doors

Adapting a stage play always presents challenges, especially one relying so heavily on precise timing and confined space. Molinaro and screenwriter Lauzier navigated this by keeping the focus tight, resisting the urge to "open it up" unnecessarily. This maintains the intensity crucial for farce. You really feel trapped with these characters. Interestingly, the film was a solid success in France upon its release, tapping into the audience's love for Pierre Richard's established persona and the enduring appeal of classic bedroom farce. While specific budget figures are elusive, its domestic success reaffirmed Molinaro's knack for popular comedy. Finding this on VHS, perhaps with slightly clunky subtitles, felt like a genuine discovery – a peek into a different comedic sensibility than the broader strokes often favored by Hollywood at the time. It’s the kind of film perfectly suited for that cozy, slightly blurry CRT viewing experience.

Why It Still Clicks

Watching Door on the Left today, what resonates is the sheer craftsmanship. It’s a reminder of how effective well-structured situational comedy can be, relying on character, plot mechanics, and perfectly timed performances rather than a barrage of one-liners. Does it feel a bit dated in its depiction of relationships? Perhaps. Boris's possessiveness is played for laughs in a way that might raise eyebrows now. Yet, the core engine – mistaken identity, spiraling panic, the absurdity of human behaviour under pressure – remains timelessly funny. It captures that specific kind of frantic energy that feels very true to the late 80s aesthetic, both in its look and its comedic pacing. It’s a nostalgic trip back to a time when a simple setup, expertly executed, could provide ninety minutes of pure, unadulterated amusement.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's near-perfect execution within its specific genre. It’s a masterfully constructed farce powered by brilliant comedic performances, particularly from Pierre Richard and Richard Bohringer. Édouard Molinaro directs with precision, ensuring the intricate clockwork plot never misses a beat. While perhaps not offering profound thematic depth, it delivers exactly what it promises: sustained, character-driven hilarity with a distinctly French flavour. It’s a delightful slice of 80s European comedy that holds up remarkably well.

Finding this tape felt like unlocking a door to pure, unpretentious fun – a reminder that sometimes, the most enjoyable cinematic experiences are the ones built on the simple, elegant chaos of human folly.