The dust never settles. It hangs thick in the air, coating the skeletal remains of a city long dead, clinging to the rusted shells of machines locked in a pointless war. Then, out of the desolation, he appears – a silhouette against a bleached sky, a lone figure burdened by circuitry and silence. This is the arrival of Omega Doom, and the uneasy quiet of this forgotten corner of the apocalypse is about to be shattered. Finding this tape on the shelf back in the day felt like unearthing a secret history, a grim fairy tale whispered between the aisles of Blockbuster.

A World Drenched in Rust

Director Albert Pyun, a name synonymous with a certain brand of ambitious, often financially challenged, 80s and 90s sci-fi action (Cyborg, Nemesis), paints his canvas here with broad strokes of decay. Omega Doom (1996) plunges us headfirst into a post-nuclear wasteland where humanity is a forgotten rumour, replaced by warring factions of sentient robots – the brutish Roms and the more sophisticated Droids. The setting, filmed amidst the stark, industrial landscapes of Slovakia, feels authentically broken. There's a tangible grit to the production design; every crumbling wall and debris-strewn street feels earned, even if the budget (reportedly around $1 million) clearly dictated a certain level of resourceful invention over expensive polish. Pyun leans heavily into slow motion and wide, static shots, letting the oppressive atmosphere of the ruined world do much of the heavy lifting. The synth score hums underneath, less a traditional soundtrack and more an ambient drone of mechanical despair.

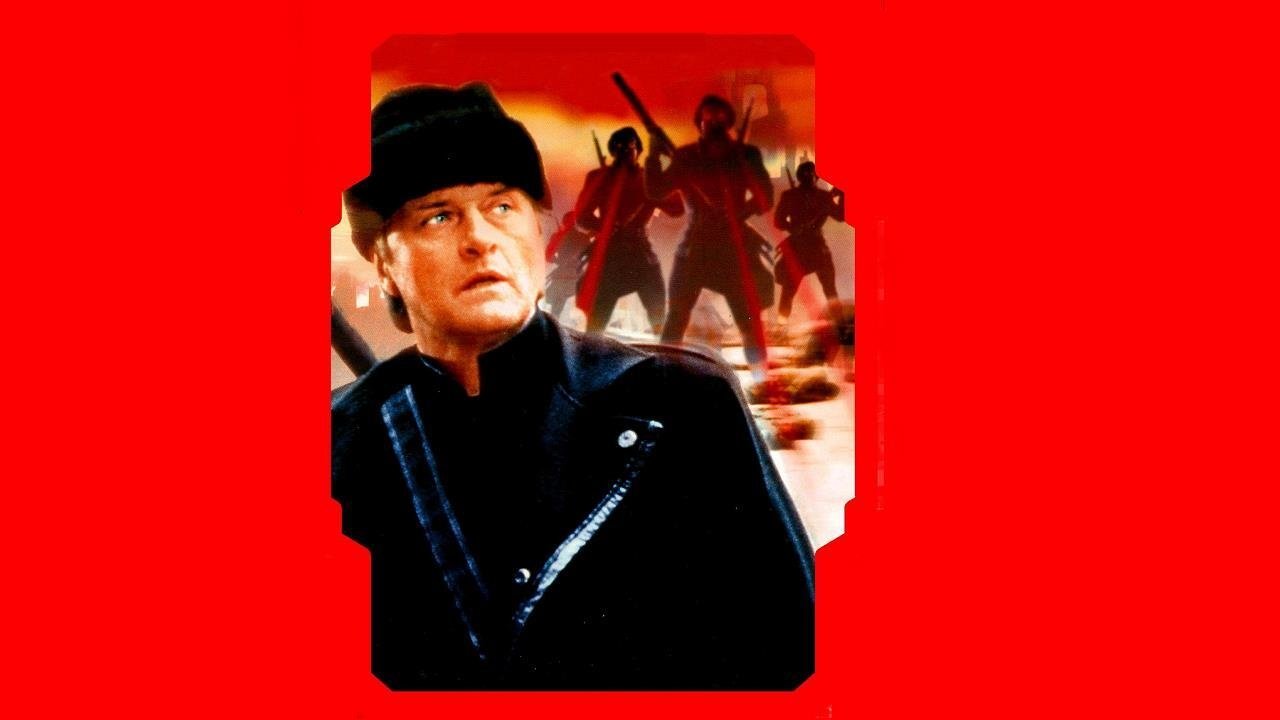

Hauer, the Silent Storm

Into this stalemate walks Omega Doom, played with weary gravitas by the legendary Rutger Hauer. Fresh off more mainstream fare but forever etched in our minds from Blade Runner (1982) and The Hitcher (1986), Hauer brings an instant weight to the proceedings. His Doom is a machine of few words, a decommissioned military unit whose programming dictates violence but whose experiences hint at something more. He’s essentially Clint Eastwood’s Man With No Name reimagined as a battle-scarred android, dropped into a narrative structure lifted directly from Kurosawa's Yojimbo (and by extension, Leone's A Fistful of Dollars). Hauer doesn't need lengthy monologues; his presence, the subtle flickers of calculation behind those piercing blue eyes, conveys everything. It’s a testament to his screen power that he elevates what could easily have been a generic robot B-movie into something more intriguing. You watch him, waiting for the inevitable eruption.

Clashing Metal and Philosophies

The plot unfolds as Doom, discovering the existence of a hidden cache of weapons, decides to play the Roms and Droids against each other. Leading the Droids is Zed (played with smarmy menace by Norbert Weisser, a familiar face from films like Midnight Express), while the Rom faction has the Head Rom and Zed's former mate, Markham (Shannon Whirry, known to many VHS aficionados from the Animal Instincts series). The conflict allows Pyun ample opportunity for stylized, slow-motion gunfights and robotic hand-to-hand combat. The practical effects, while undeniably dated now, had a certain charm on CRT screens – sparks fly, limbs are severed (often revealing surprisingly low-tech wiring beneath), and oil sprays like blood. It's clunky, sure, but there's an earnestness to it. Remember how impressive even rudimentary robot effects felt back then, before CGI smoothed everything over?

Pyun's Persistent Vision

This film is pure Albert Pyun. It revisits themes common in his work: the aftermath of societal collapse, the nature of humanity (or its absence), lone warriors navigating treacherous landscapes, and a distinctive visual aesthetic achieved despite budgetary constraints. Co-writing with Ed Naha (who penned the cult favourites Dolls and Troll), Pyun crafts a story that feels both derivative and uniquely his own. It’s a film clearly made for the direct-to-video market that thrived in the mid-90s, a place where ambitious concepts could find life, even without studio backing. Trivia buffs might note that Pyun often shot films back-to-back or in quick succession in cost-effective locations like Eastern Europe or the Philippines during this era, maximizing resources to get his distinct visions onto tape. Omega Doom fits snugly into that productive, if sometimes rough-edged, period.

Echoes in the Wasteland

Does Omega Doom achieve profound philosophical insights? Perhaps not consistently. But beneath the robot-on-robot violence and the Yojimbo framework, there are glimmers. Hauer's character, a machine built for war who ultimately seeks peace (or perhaps just oblivion), carries a certain melancholy resonance. The film asks, albeit bluntly, what remains when the creators are gone? Can loyalty, betrayal, and even a twisted form of community exist purely among machines? It doesn't offer easy answers, content instead to let the bleak atmosphere and Hauer's stoic performance linger.

Rating: 6/10

Omega Doom is undeniably a product of its time and budget. The pacing can drag, the supporting performances are uneven, and the action, while stylishly shot by Pyun, lacks the kinetic punch of bigger-budget fare. Yet, it succeeds precisely because of its limitations, not despite them. Hauer is magnetic, the atmosphere is genuinely thick with post-apocalyptic dread, and the Yojimbo-with-robots premise holds a unique appeal. It’s a quintessential slice of mid-90s DTV sci-fi, a perfect late-night watch discovered on a dusty VHS tape. It might not be a masterpiece, but its moody ambiance and Hauer's iconic presence make it a fascinating relic.