Sometimes a film doesn't arrive with explosions or high-concept hooks, but with the quiet hum of tires on asphalt, carrying characters toward a future as uncertain as their past was confining. That's the feeling that lingers from Wayne Wang's 1999 drama, Anywhere but Here. It settles not with a bang, but with the slow, resonant ache of recognition – the complex push and pull between a parent's dreams and a child's reality. Watching it again recently, it wasn't the plot mechanics I remembered most vividly, but the almost painful authenticity of the central relationship, a testament to the powerhouse performances at its core.

An Unlikely Duo on the Road

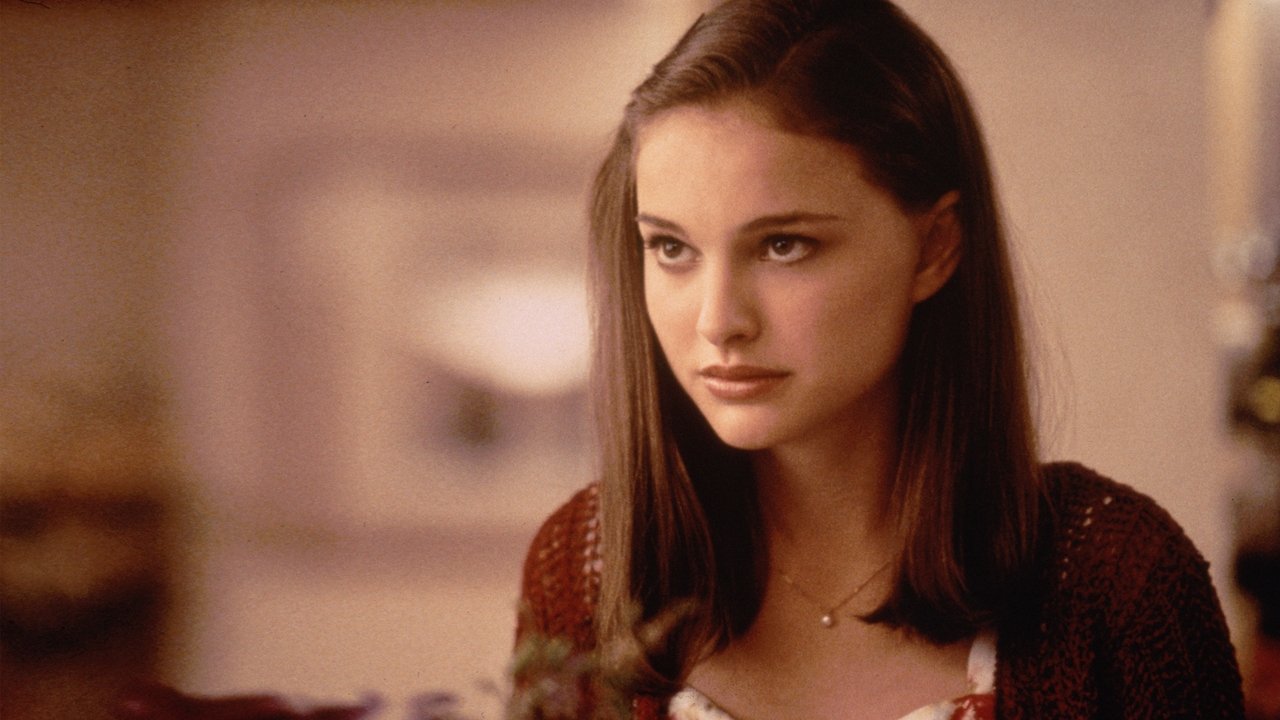

At the heart of Anywhere but Here are Adele August (Susan Sarandon) and her teenage daughter, Ann (Natalie Portman). Adele, flamboyant, impulsive, and forever chasing a more glamorous life she feels she deserves, abruptly packs up their life in small-town Wisconsin, dragging a reluctant Ann to the sun-drenched, intimidating landscape of Beverly Hills. Adele dreams of movie stars and wealthy husbands; Ann dreams of stability, college on the East Coast, and escaping her mother's chaotic orbit. It’s a classic odd couple setup, but filtered through the intense, often suffocating bond of mother and daughter.

What makes the film resonate, even years later, is how brilliantly Sarandon and Portman embody these roles. Sarandon, already an icon following films like Thelma & Louise (1991) and her Oscar-winning turn in Dead Man Walking (1995), crafts Adele not as a caricature of a bad mother, but as a deeply flawed, frustratingly charismatic woman fueled by insecurity and misguided love. Her optimism often borders on delusion, her parenting methods are questionable at best (remember the disastrous car purchase?), yet Sarandon infuses her with a vulnerability that prevents us from writing her off entirely. You understand why Ann feels both exasperated and fiercely protective.

And then there's Portman. Just 18 at the time of release, and sharing the screen with the already-legendary Sarandon, she delivers a performance of remarkable maturity and nuance. Ann is the adult in the room, shouldering the weight of her mother's whims while desperately trying to carve out her own identity. Portman conveys Ann's quiet intelligence, her simmering resentment, and her profound love for Adele with a subtlety that’s captivating. It's a far cry from her role as Queen Amidala in Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace, released the very same year, showcasing an incredible range early in her career. Their chemistry is electric – a volatile mix of love, anger, codependency, and fierce loyalty that feels utterly real.

Beyond the Surface Sparkle

Director Wayne Wang, known for his sensitive handling of complex relationships in films like The Joy Luck Club (1993), wisely keeps the focus tight on his leads. Beverly Hills isn't just a backdrop of palm trees and swimming pools; it's a symbol of the elusive happiness Adele chases, a place where their financial struggles and emotional disconnect feel even more pronounced against the facade of wealth and success. The screenplay, adapted by the great Alvin Sargent (who penned Ordinary People (1980) and would later adapt the Spider-Man films) from Mona Simpson's 1986 novel, avoids easy resolutions. It understands that growth, particularly in fraught family dynamics, is often incremental and painful.

It’s fascinating to learn that Portman initially hesitated to take the role due to a planned scene involving nudity. Reportedly, both Sarandon and Wang advocated for its removal from the script to secure her involvement, a decision that feels right for the film’s tone and respects the integrity of Ann's journey. It speaks volumes about the collaborative spirit and the commitment to getting the emotional core right. This wasn't a film relying on shock value, but on the power of its central performances and the truth of its story.

Another interesting footnote, often shared among literary circles, is that author Mona Simpson is the biological sister of Apple co-founder Steve Jobs. While the novel isn't strictly autobiographical, knowing this connection adds a layer of poignant context to its themes of searching for connection and identity, often against the backdrop of California dreams.

Finding Home, Even When Running

Anywhere but Here wasn’t a massive box office smash – earning around $18.6 million against a $23 million budget – which perhaps explains why it sometimes feels like a half-remembered title from the late-90s rental shelves. Yet, its power hasn't diminished. It captures that specific late-adolescent feeling of yearning for independence while still being tethered to family, the confusing mix of wanting to escape and needing to belong. It asks us: what do we owe our parents' dreams? And what happens when those dreams clash fundamentally with our own?

The film doesn’t offer easy answers, and Adele never has a complete, movie-miracle transformation. That's part of its strength. It portrays the reality that sometimes, love means accepting imperfections, finding ways to navigate dysfunction, and understanding that "home" isn't always a place, but sometimes a person – even a maddeningly difficult one.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's exceptional core performances, particularly the dynamic between Sarandon and Portman, which elevates the material significantly. The direction is sensitive, the adaptation thoughtful, and the emotional resonance remains potent. It avoids melodrama, offering a grounded and often painfully relatable look at a complex mother-daughter relationship. While perhaps lacking the commercial punch of other late-90s releases, its quiet power and authentic portrayal of familial bonds make it a standout drama from the era, well worth revisiting or discovering.

What truly lingers is the quiet strength found in Ann's journey – the realization that sometimes, finding your own way means understanding, forgiving, and ultimately loving the person you desperately needed to get away from.