It begins not with a bang, but with the muffled sounds of polite conversation filtering through apartment walls during a New York City Christmas season. 1990's Metropolitan doesn't crash onto the screen; it drifts in, like an unexpected guest at an endless series of debutante balls, carrying with it a distinct air of intellectual chatter, social anxiety, and the faint scent of mothballed aristocracy. Finding this on a video store shelf back in the day, nestled perhaps between a Stallone actioner and a John Hughes comedy, must have felt like stumbling upon a hidden frequency, a broadcast from a world both familiar and strangely alien.

After the Ball is Over

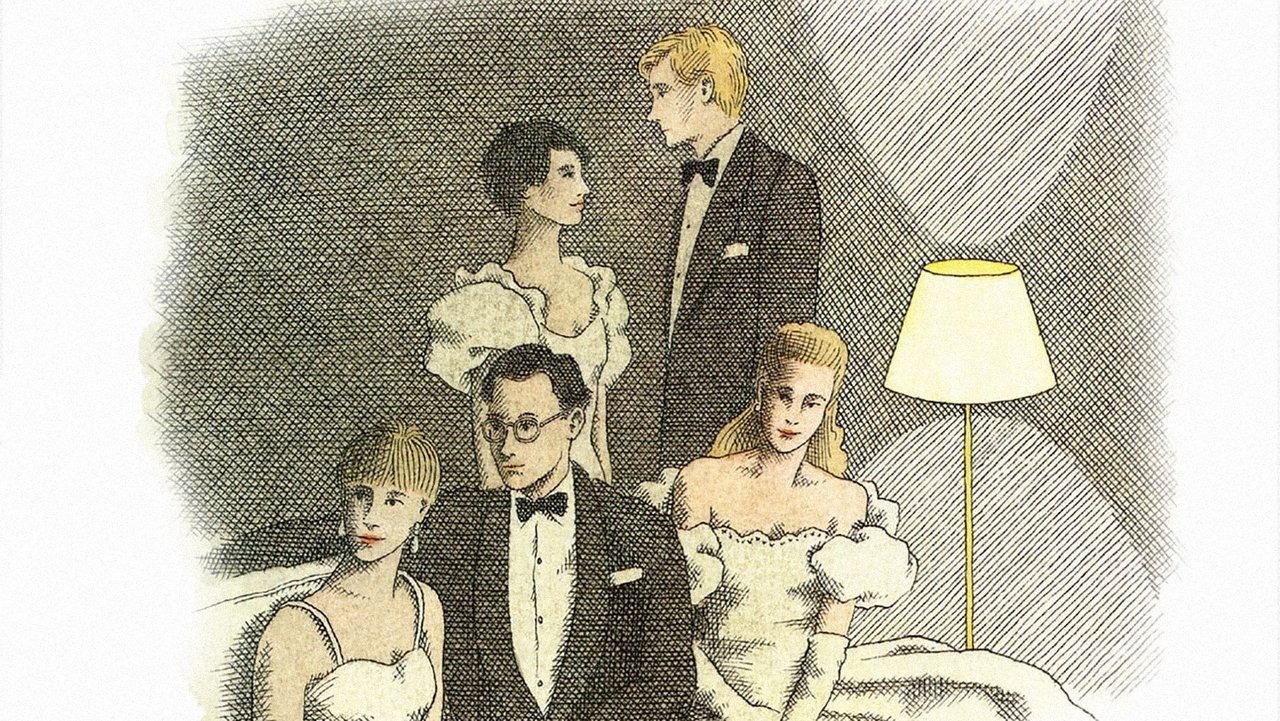

What Whit Stillman achieved with his directorial debut is nothing short of remarkable, especially considering its creation story. Metropolitan invites us into the rarefied world of the "UHB" – the Urban Haute Bourgeoisie – a group of privileged Manhattanites navigating the dwindling rituals of debutante season. They gather in borrowed Park Avenue apartments after the official galas wind down, clad in formalwear, dissecting Fourier, debating the merits of Jane Austen, and nursing anxieties about their seemingly preordained futures. It's a setting that could easily feel dated or exclusionary, yet Stillman’s sharp, witty script and his affection for these characters make it unexpectedly compelling. He captures a specific moment, a specific class, with anthropological precision yet deep empathy. You don't need to have attended a deb ball to recognize the universal awkwardness of youth, the yearning for connection, and the fumbling attempts to define oneself through intellectual posturing.

The Eloquence of Insecurity

The absolute engine of Metropolitan is its dialogue. Oh, that dialogue! It’s hyper-literate, endlessly analytical, frequently hilarious, and delivered with a kind of earnest self-importance that never quite curdles into smugness. These young people talk constantly, circling topics of social decline, romantic entanglements, and existential purpose with the kind of verbose intensity only possible when you have too much time and education on your hands. Listening to them feels like eavesdropping on the world’s most articulate study group, fueled by late-night anxieties rather than coffee.

Leading the verbal charge is the unforgettable Nick Smith, played with cynical brilliance by Chris Eigeman in a star-making turn. Nick is the self-appointed theorist and critic of the group, dispensing pronouncements on social mobility ("The Cha-Cha is no longer viable"), delivering deadpan critiques ("You're obviously familiar with the concept of 'downward mobility'"), and revealing glimpses of vulnerability beneath his world-weary facade. Eigeman’s performance is a masterclass in dry wit and wounded pride; he makes Nick infuriating, hilarious, and ultimately quite poignant. It’s the kind of performance that lodges itself in your memory, the lines echoing long after the credits roll. My friends and I certainly spent a good chunk of the early 90s quoting his pronouncements, much to the confusion of anyone outside our little film geek circle.

An Outsider's Gaze

Our guide into this hermetic world is Tom Townsend (Edward Clements), a West Sider and self-proclaimed socialist who finds himself swept into the UHB orbit more by accident than design. Tom is less wealthy, more overtly idealistic (though profoundly influenced by literary critics), and possesses a touching awkwardness. His burgeoning relationship with the thoughtful, Austen-loving Audrey Rouget (Carolyn Farina) forms the film's gentle romantic core. Farina brings a quiet intelligence and sincerity to Audrey, making her perhaps the most genuinely grounded character amidst the intellectual fireworks. Clements, in his only major film role, perfectly captures Tom's outsider status and intellectual earnestness. Their dynamic provides a necessary emotional anchor.

From Apartment Sale to Oscar Nod: A True Indie Tale

The story behind Metropolitan is almost as charming as the film itself. Whit Stillman, drawing heavily on his own youthful experiences, famously funded the film partly by selling his own apartment, raising the rest of the modest $230,000 budget from friends and relatives. Shot over just a few weeks during the winter of 1989, often using borrowed locations and relying on the cast's own formalwear (or lack thereof – Tom's rented tux becomes a minor plot point), the film has an intimate, almost home-movie feel that belies its sophisticated script. This wasn't a slick studio production; it was a passion project born of necessity and wit. Its subsequent success – earning over $2.9 million at the box office, critical acclaim (garnering strong reviews at Sundance), and culminating in a surprise Academy Award nomination for Best Original Screenplay for Stillman – felt like a victory for thoughtful, personal filmmaking in an era increasingly dominated by blockbusters. It proved that sharp writing and keenly observed characters could resonate just as powerfully as explosions or special effects.

A Time Capsule with Lasting Questions

Watching Metropolitan today feels like opening a perfectly preserved time capsule. The fashion, the specific cultural references, the very existence of this particular social scene – it all speaks to a specific moment just before the cultural shifts of the 90s truly took hold. Yet, the film transcends mere nostalgia. The characters' anxieties about failure, their grappling with complex ideas, their fumbling attempts at love and friendship – these remain remarkably relevant. Doesn't every generation worry about its place in the world? Don't we all engage in a certain amount of intellectual performance, especially when young? The film asks us to consider the nature of social structures, the meaning we derive from tradition (even fading ones), and the ways we try, often clumsily, to connect with one another.

It’s a film that rewards rewatching, revealing new layers in the dialogue and character interactions each time. It possesses a gentle melancholy, a sense of observing the end of something without quite knowing what comes next – a feeling many of us can likely relate to, looking back from the vantage point of decades hence.

Rating: 9/10

Metropolitan earns this high score for its singular vision, its brilliantly witty and insightful script, Chris Eigeman's iconic performance, and its remarkable achievement as a low-budget indie phenomenon. It perfectly captures a specific milieu while exploring universal themes of youth, identity, and belonging. The dialogue alone makes it essential viewing. Its slight narrative drift and occasionally mannered performances might not connect with everyone, but for those attuned to its unique frequency, it’s a deeply intelligent and enduringly charming piece of work.

It leaves you pondering not grand dramatic gestures, but the quiet currents beneath polite conversation, and the poignant comedy of smart young people trying desperately to figure it all out, one verbose, tuxedoed night at a time. A true gem from the shelves of VHS Heaven.