There's a certain texture to the asphalt realism of late 70s cinema, a grainy honesty that feels worlds away from the gloss that would soon dominate the 80s. Boulevard Nights (1979) lives entirely within that texture. Watching it again after all these years, perhaps on a worn VHS tape pulled from the back of the shelf, it doesn't feel like a romanticized genre piece. Instead, it feels like stepping onto the streets of East Los Angeles, breathing in the specific air of a community caught between tradition and the harsh pressures of the modern world. It's a film that stays with you, not for explosive action, but for its quiet, simmering tension and the weight of its inevitable tragedy.

Brothers, Dreams, and Dead Ends

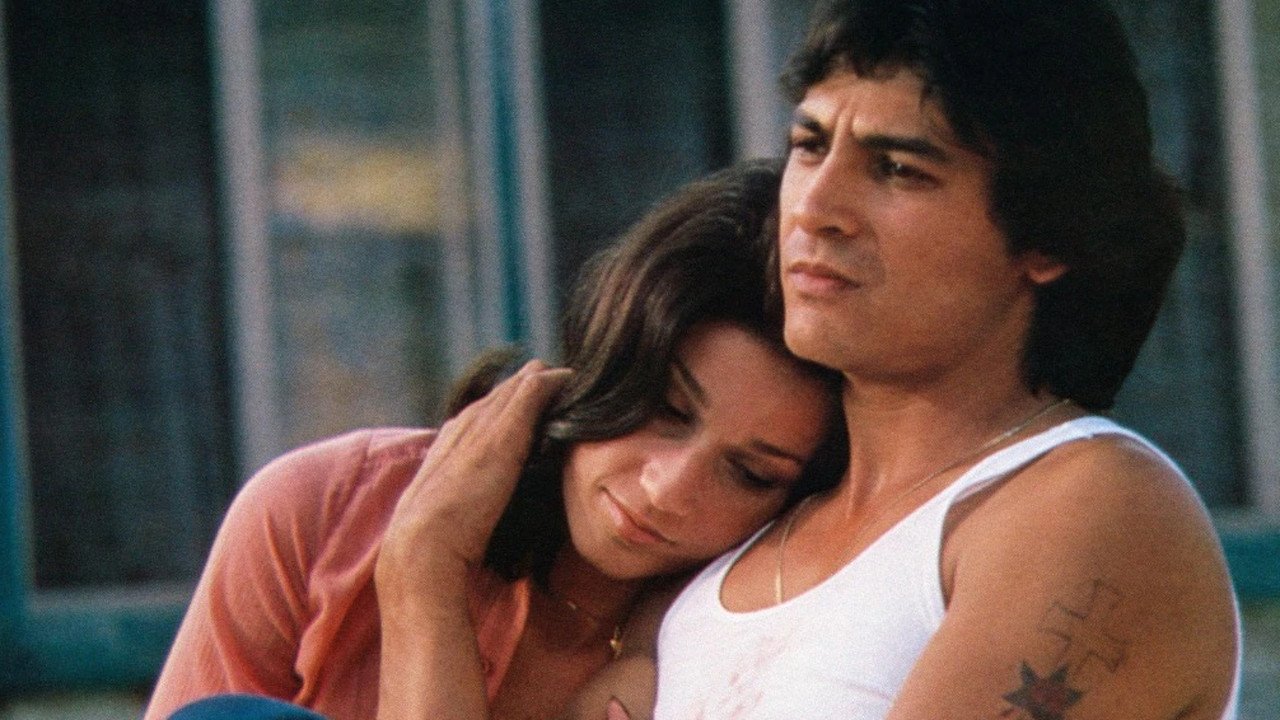

At its heart, Boulevard Nights is a story about two brothers, Raymond (a compelling Richard Yniguez) and Chuco (Danny De La Paz in a star-making, volatile performance). Raymond is trying to build a life – he has a steady job at an auto body shop, dreams of owning his own place, and is deeply in love with Shady (Marta DuBois). He represents the hope of moving forward, embracing responsibility while still honoring his roots, symbolized by his meticulously cared-for lowrider. Chuco, on the other hand, is adrift, inexorably pulled towards the gang life (the VGV, Varrio Grande Vista) and its promises of belonging and respect, however fleeting and dangerous. Their diverging paths form the film's central, heartbreaking conflict. What does loyalty mean when your blood is pulling you towards self-destruction?

Yniguez portrays Raymond with a quiet strength and weariness that feels utterly authentic. You see the weight of the world on his shoulders, the constant effort to keep his younger brother safe, the frustration warring with deep familial love. But it's De La Paz as Chuco who often steals the focus. He embodies the restless energy, the desperate need for validation, and the fatalistic bravado of a young man convinced the streets are his only option. It's a performance crackling with unprocessed pain and youthful defiance, making Chuco both infuriating and deeply sympathetic. His choices might be destructive, but the film makes us understand the forces pushing him towards them.

Authenticity Over Exploitation

Directed by Michael Pressman, who would later navigate very different tones with films like Doctor Detroit (1983), Boulevard Nights distinguishes itself through its commitment to realism. Unlike the stylized urban fantasies that sometimes populated the era (think The Warriors, also 1979, which is brilliant in its own way), this film feels grounded, almost documentary-like at times. Pressman insisted on filming entirely on location in East Los Angeles neighborhoods like Boyle Heights, capturing the specific visual language of the murals, the corner stores, the sun-baked streets.

This commitment extended to the casting of extras and advisors. Many were actual residents and members of local car clubs, lending an undeniable layer of authenticity to the cruising scenes and background interactions. Reportedly, this even led to some real-life tensions simmering between rival groups present on set, a stark reminder of the reality the film was depicting. The lowriders themselves, central symbols of pride and artistry within the culture, weren't Hollywood creations but lovingly maintained vehicles provided by the community. It’s this dedication to capturing a specific place and time, without resorting to easy stereotypes, that gives the film its enduring power. It wasn't necessarily a massive box office hit (made for around $2.5 million, grossing about $8 million – respectable, but not a blockbuster), and initial reviews were mixed, grappling with its raw portrayal, but its significance within Chicano cinema is undeniable.

The Weight of Atmosphere

The film's pacing is deliberate, mirroring the slow cruise of a lowrider down Whittier Boulevard. It allows the atmosphere to seep in – the warm nights, the camaraderie, the ever-present undercurrent of danger. The violence, when it erupts, feels clumsy, brutal, and devoid of glamour. It’s shocking because it feels real, not choreographed. This isn't about cool anti-heroes; it's about the devastating consequences of postcode rivalries and cycles of retaliation.

One fascinating detail often overlooked is the film's genesis. While E. Gary Stickney received screenplay credit, the initial story concept reportedly came from someone with direct ties to the community, aiming to tell a story from the inside out. While details are murky, this potential origin speaks to the film's desire to be more than just an outsider's perspective. It sought to capture the nuances – the importance of family, the code of the streets, the beauty found in the customized cars – alongside the tragedy.

Legacy on the Boulevard

Does Boulevard Nights feel dated? In some ways, inevitably. The fashion, the slang, the specific social dynamics are rooted firmly in the late 70s. Yet, the core themes – the struggle for identity, the destructive allure of gang life versus the pursuit of a different future, the unbreakable bonds and unbearable strains within families – remain painfully relevant. It stands as an important precursor to later films exploring similar territories, like Stand and Deliver (1988) or American Me (1992), offering a less sensationalized, more intimate look at the pressures facing young Chicanos in urban America. It asks profound questions about environment versus choice, and the weight of expectations, both internal and external. What truly defines loyalty when paths diverge so drastically?

Finding this on VHS back in the day, perhaps expecting a straightforward action flick, was always a bit jarring. Its quiet intensity and refusal to offer easy answers made it stand out. It wasn't always an easy watch, but it felt important, like a window into a world rarely depicted with such sincerity on screen.

Rating: 7.5/10

Boulevard Nights earns its score through its powerful, authentic performances, particularly from Danny De La Paz, its immersive atmosphere, and its unflinching, non-exploitative portrayal of a specific time, place, and culture. While its deliberate pacing might test some viewers accustomed to faster narratives, its commitment to realism and the emotional weight of its central sibling tragedy make it a significant and affecting piece of late 70s cinema. It avoids easy moralizing, instead presenting a complex situation with empathy and honesty.

It remains a poignant, often somber cruise through the heart of East LA, leaving you contemplating the dreams deferred and the lives altered on those unforgiving streets.