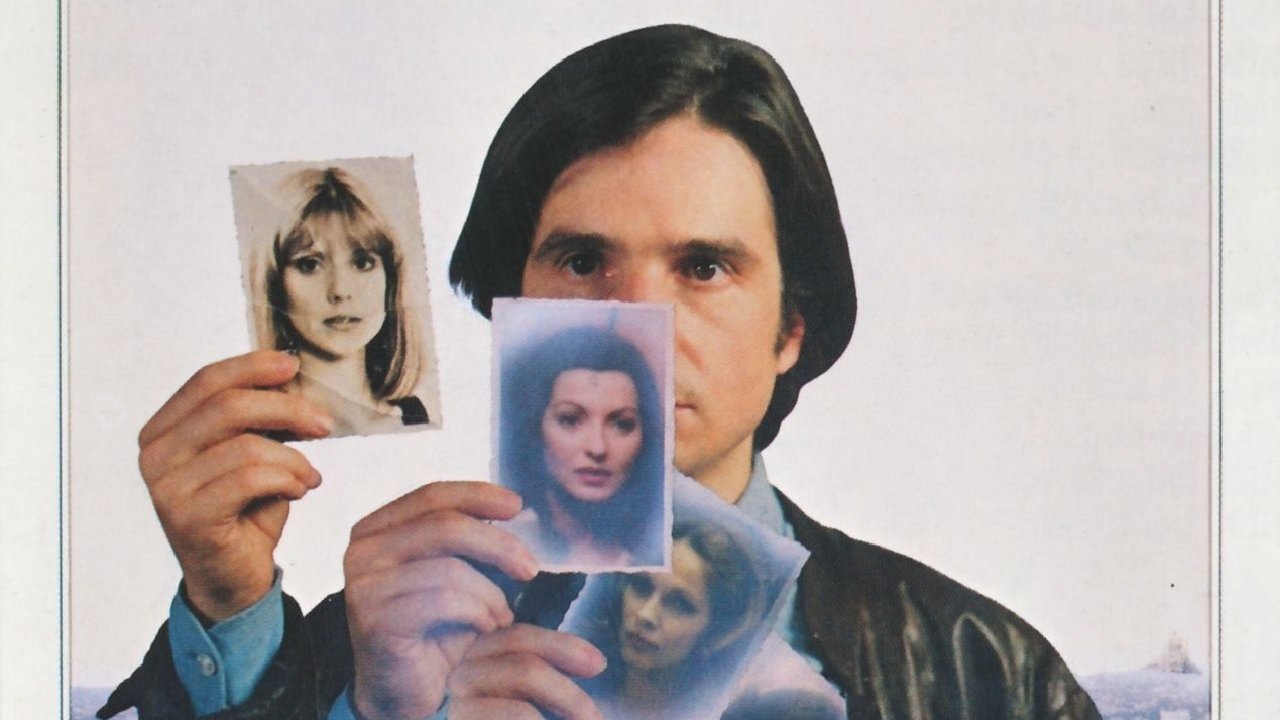

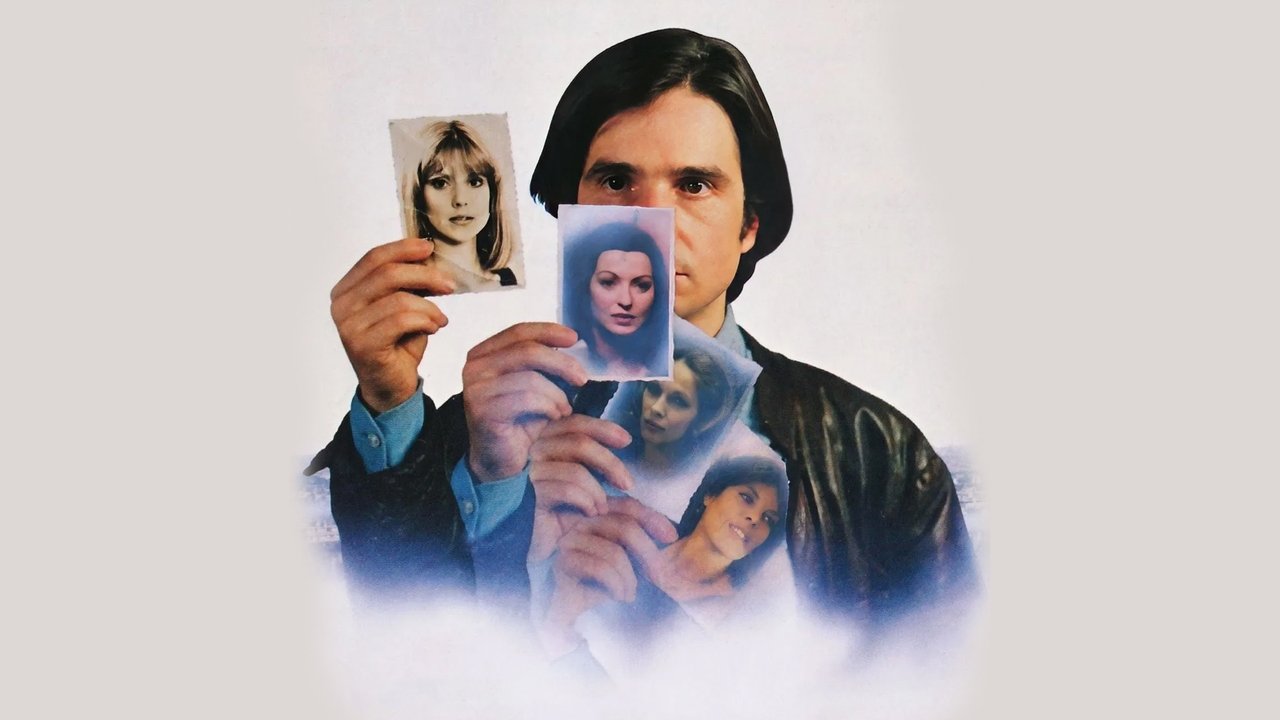

Okay, settle in and grab a drink. We're diving into something a bit different today, a film that feels less like a single movie and more like revisiting pages scattered from a well-worn diary. I'm talking about François Truffaut's Love on the Run (L'amour en fuite), released in 1979. Finding this one on a dusty VHS shelf, perhaps tucked away in the 'Foreign Language' section that always felt a little intimidating but promised hidden gems, was like uncovering the final chapter of a story you didn't even realize you'd been following.

### A Farewell to Antoine

What strikes you immediately about Love on the Run isn't necessarily a bombastic opening, but a sense of summation. It's the fifth and final installment in Truffaut's chronicle of Antoine Doinel, a character who grew up on screen alongside his audience. We first met him as a troubled adolescent in the groundbreaking The 400 Blows (1959), and here we find him navigating his early thirties, facing divorce from Christine (Claude Jade) and embarking on a new relationship with Sabine (Dorothée). But this isn't just a new chapter; it’s a conscious look back, an attempt to piece together the fragments of a life lived through love, loss, and impulsive decisions.

The film catches Antoine at a moment of transition, literally on a train where he encounters Colette (Marie-France Pisier), a significant figure from his romantic past (Antoine and Colette, Stolen Kisses). Their conversation becomes a catalyst for reflection, weaving together Antoine's present with vivid flashbacks drawn directly from the previous four films.

### Cinema as Memory Box

This is where Love on the Run truly distinguishes itself, and perhaps where its charm—and for some, its frustration—lies. Truffaut doesn't just reference the past; he incorporates significant chunks of footage from the earlier Doinel films. Seeing a younger Jean-Pierre Léaud as the hopeful, awkward, or heartbroken Antoine of years gone by, juxtaposed with the slightly wearier, perhaps only marginally wiser, man he has become, is uniquely poignant. It’s a technique that turns the film itself into an act of memory.

Did it always work seamlessly? Perhaps not. Critics at the time, and viewers since, have sometimes found it leans heavily on nostalgia, feeling occasionally like a 'greatest hits' compilation rather than a wholly original narrative. Yet, there's an undeniable power to it. Watching those black and white moments from The 400 Blows flicker within this colour film from '79… it forces a confrontation with time itself. How many characters do we get to see age so authentically on screen, portrayed by the same actor across two decades? It’s a rare, affecting cinematic experience. I remember watching this years ago, likely on a slightly fuzzy CRT, and feeling that pull of time—not just Antoine's, but my own.

Interestingly, Marie-France Pisier, who plays Colette, also co-wrote the screenplay with Truffaut and Jean Aurel. This adds another layer of meta-commentary, with the actress who embodied one of Antoine's formative relationships actively shaping his final narrative reflection. It lends a particular weight to Colette's observations about Antoine's patterns and enduring character traits.

### The Enduring Enigma of Doinel

Jean-Pierre Léaud is Antoine Doinel. It's impossible to separate actor and character. In Love on the Run, Léaud carries the weight of that history effortlessly. There's still the restless energy, the romantic idealism often colliding with self-absorption, but it's tempered now with a hint of melancholy. He's still chasing something, but is he any closer to understanding what? Does Antoine ever truly grow up, or does he just learn to articulate his charming evasions more eloquently? These are the questions the film leaves lingering.

The return of Claude Jade as Christine provides a necessary anchor. Her perspective on their marriage and separation feels grounded and mature, often serving as a counterpoint to Antoine's more flighty nature. Their interactions carry the bittersweet weight of shared history, affection mixed with exasperation.

### Not Quite a Blockbuster, But Something More

Let's be honest, Love on the Run wasn't the kind of tape you'd grab for a Friday night pizza party like, say, Die Hard or Ghostbusters. This was something quieter, more thoughtful. It didn't smash box office records (its French box office was respectable but not huge compared to earlier entries) and its reception was more mixed than the rapturous welcomes afforded to The 400 Blows or Stolen Kisses. Some found its reliance on past glories a sign of Truffaut perhaps running out of steam with the character.

Yet, viewed now, especially through the lens of time and perhaps our own accumulated life experiences, the film resonates differently. It’s a meditation on how we construct narratives about our own lives, how memory shapes our understanding of love, and how the people we were continue to echo in the people we become. Isn't that something we all grapple with as the years stack up? What does looking back truly teach us?

The film doesn't offer easy answers. Antoine remains charmingly, frustratingly himself. His future with Sabine feels uncertain, another potential repetition of past patterns. But maybe that's the point. Truffaut leaves Antoine, and us, not with a neat conclusion, but with the ongoing, messy business of living and loving.

***

Rating: 7/10

Justification: Love on the Run earns a 7 for its unique, if sometimes flawed, structure and its poignant culmination of one of cinema's most enduring character studies. While it relies heavily on recycled footage and may lack the standalone punch of earlier Doinel films, its reflective tone, Léaud's career-defining portrayal, and its brave confrontation with time and memory make it a significant and moving farewell. It's not perfect, but its ambition and emotional resonance linger.

Final Thought: It’s a film that feels like rereading old letters – filled with fondness, perhaps a touch of regret, and the undeniable sense that the person writing them is still, somehow, wonderfully and maddeningly, the same. A fittingly complex adieu to Antoine Doinel.