Ah, the late 70s bleeding into the 80s on home video – a time when movie stars felt larger than life, and sometimes, they even wore lightbulbs. Flickering onto the screen from countless rental tapes came Sydney Pollack's 1979 offering, The Electric Horseman, a film that rode a unique line between contemporary western, romantic drama, and a surprisingly gentle critique of corporate America. It wasn't necessarily the flashiest tape on the shelf, maybe nestled between louder action flicks or sci-fi epics, but pulling this one felt like settling in for something substantial, something with genuine star power and a quiet heart beating beneath the neon glow.

Vegas Lights, Prairie Flights

The premise itself has that classic Hollywood shine: Norman "Sonny" Steele, played with world-weary charm by Robert Redford, is a five-time World Champion rodeo cowboy whose glory days are long gone. Now, he’s reduced to being the face of AMPCO, a giant conglomerate, trotting out in an embarrassing, light-up suit (more on that marvel later) to endorse Ranch Breakfast cereal at sterile corporate events. His co-star in these debasing spectacles is Rising Star, a multi-million dollar thoroughbred racehorse, similarly drugged and diminished for marketing purposes. One hazy Las Vegas night, Sonny decides he's had enough. In a moment of quiet rebellion fuelled by booze and conscience, he rides Rising Star off the casino stage and heads out into the desert, aiming to set the magnificent animal free. Enter Hallie Martin (Jane Fonda), a sharp television reporter who initially sees Sonny's stunt as just the kind of sensational story that could catapult her career.

A Different Kind of Ride

What unfolds isn't a high-octane chase, but something more measured and character-driven. Yes, Hallie tracks Sonny down, and yes, there's a pursuit by the authorities and AMPCO's less-than-scrupulous handlers. But the real core of The Electric Horseman lies in the evolving relationship between Sonny and Hallie, and their shared journey across the stunning landscapes of Utah. Pollack, who directed Redford in classics like Jeremiah Johnson and Three Days of the Condor, knew exactly how to frame his star against the rugged beauty of the American West. The contrast between the artificiality of Las Vegas and the wide-open freedom of the wilderness is a visual theme Pollack uses masterfully.

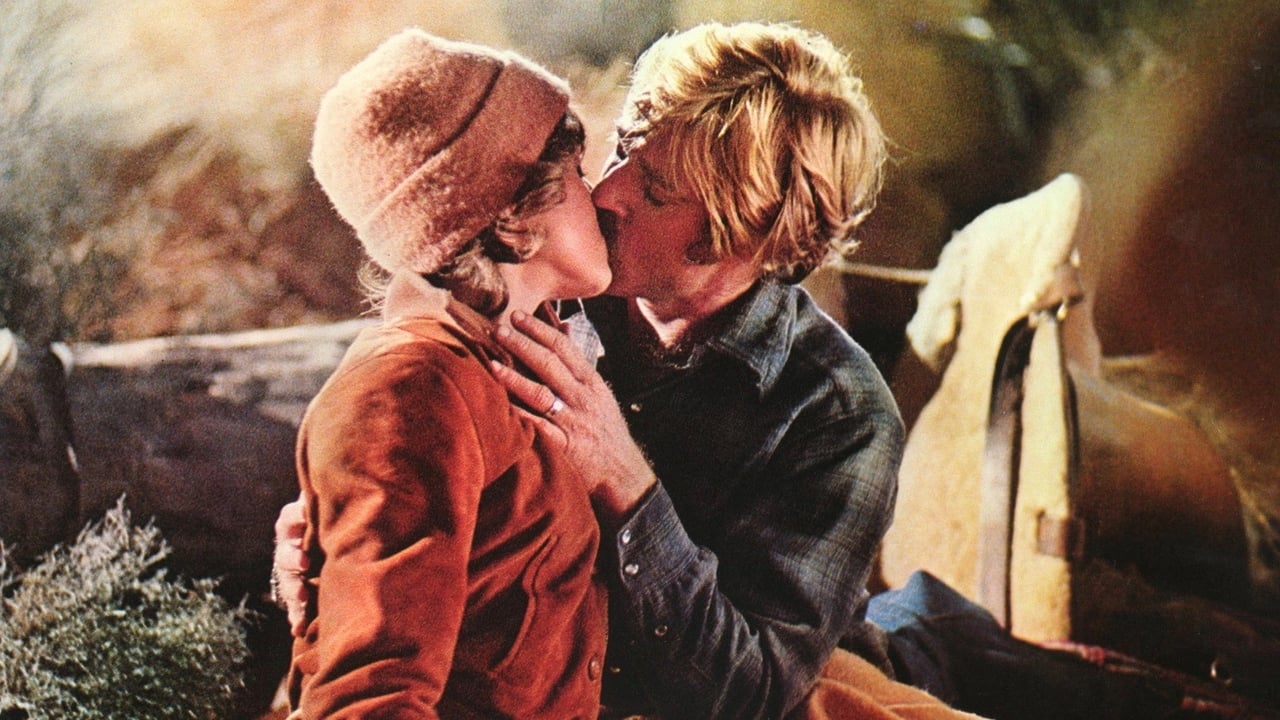

The chemistry between Redford and Fonda, reteaming years after their youthful energy in Barefoot in the Park (1967) and the heavier The Chase (1966), is undeniable. Here, it’s matured into something quieter, more nuanced. Sonny is broken but principled, a man rediscovering his soul far from the commercial glare. Hallie starts as cynical and career-driven, but the journey, and Sonny's quiet integrity (along with some shared campfire coffee), gradually melts her professional armor, revealing a woman capable of genuine empathy. Their banter feels natural, their growing connection earned rather than forced. We also get a memorable supporting turn from Valerie Perrine as Sonny's sympathetic ex-wife.

Retro Fun Facts: Suits, Steeds, and Songs

That electric suit! It’s impossible to discuss this film without picturing Redford blinking like a Christmas tree. Reportedly costing around $75,000 back in '79 (that's nearly $300k today!), the suit was apparently quite heavy – estimates range, but upwards of 40-50 pounds seems likely – and powered by a hefty battery pack. You can almost feel Redford’s discomfort, which perfectly mirrors Sonny’s own humiliation. It’s a brilliant, slightly absurd visual metaphor for how far the cowboy has fallen.

And Rising Star? The prized horse was primarily played by a five-year-old thoroughbred named Let's Merge, portraying the grace and spirit Sonny felt compelled to save. The film's gentle message about animal welfare, particularly regarding the drugging of the horse for compliance, feels surprisingly ahead of its time.

We also can’t forget the soundtrack, infused with the melancholic warmth of country music, most notably featuring Willie Nelson. His rendition of "Mammas Don't Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys" became inextricably linked with the film, perfectly capturing its elegiac tone about a fading way of life. Penned by Robert Garland (based on a story he conceived with Paul Gaer), the script found favour with audiences, helping the film gross over $61 million domestically on a $12.5 million budget – a solid hit that kept it circulating in video stores for years. Initial reviews were generally positive, too, reflected in its decent IMDb score (currently 6.4) and strong Rotten Tomatoes rating (81% fresh).

Why It Still Glows

Watching The Electric Horseman today feels like revisiting a gentler kind of Hollywood filmmaking. It takes its time, allowing moments of silence and scenic beauty to land. The critique of corporate homogenization feels perhaps even more relevant now, though the film delivers it without cynicism, opting instead for a hopeful belief in individual action. It’s the kind of movie that might have felt a little slow even back in the day if you were expecting non-stop action, but its charm lies in its sincerity and the magnetic presence of its leads. You believe in Sonny’s quest and Hallie’s transformation. Seeing those vast landscapes fill a fuzzy CRT screen might have even amplified the sense of escape Sonny was seeking – a brief respite from the everyday, right there in your living room. Remember arguing with your sibling about who got to rewind the tape carefully? This was one worth preserving.

The Verdict

The Electric Horseman isn't trying to be the most exciting film ever made, but it succeeds wonderfully at being exactly what it is: a thoughtful, beautifully shot, and superbly acted character piece with a gentle romance at its core. It captures a specific late-70s mood – a disillusionment with modern excess coupled with a yearning for authenticity. The star power is undeniable, the scenery breathtaking, and the central message about finding freedom, both for the horse and the man, resonates quietly but effectively. It might move at a canter rather than a gallop, but it’s a ride well worth taking again.

Rating: 7/10 - A warm, well-crafted film powered by iconic star chemistry and stunning visuals. Its pacing might feel leisurely to some, but its sincerity and gentle critique of commercialism give it an enduring charm that justifies its place as a beloved rental memory.

It’s a film that reminds us sometimes the brightest lights aren’t on a Vegas stage, but out under a vast, desert sky. And maybe, just maybe, you don't need a million-dollar horse to feel free.