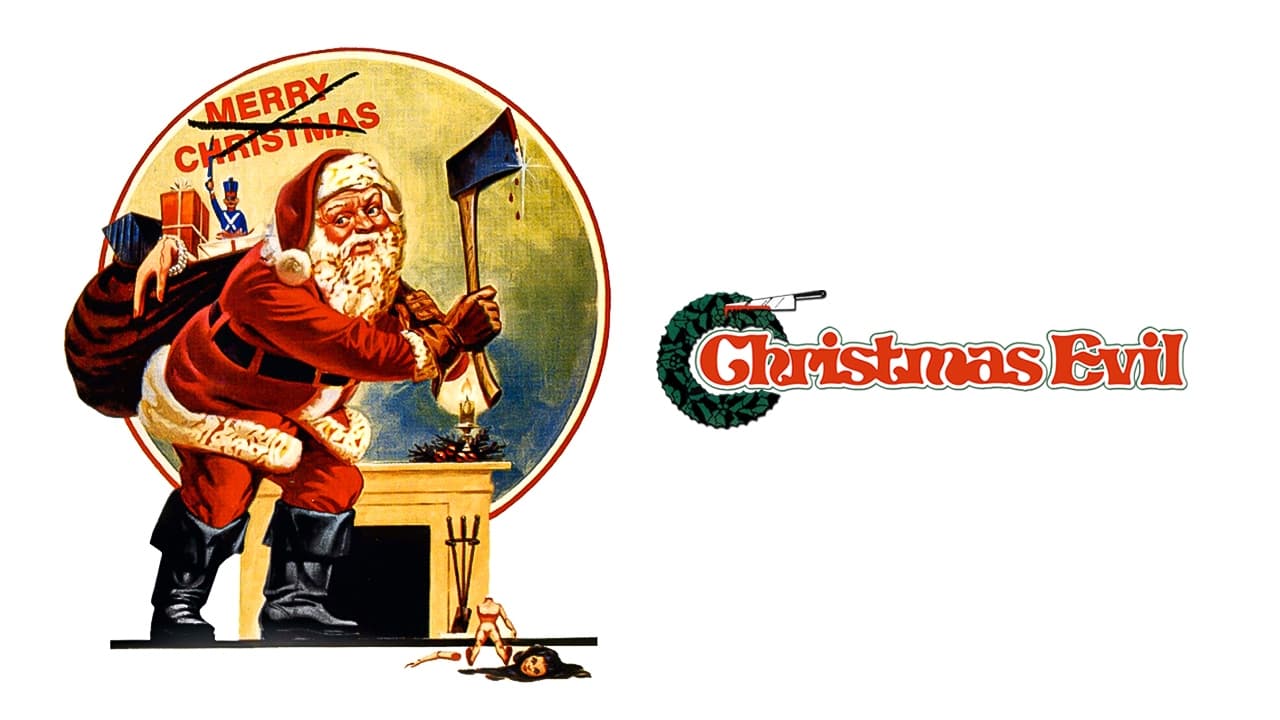

Forget the twinkling lights and saccharine carols for a moment. Cast your mind back to the flickering glow of a rented tape, perhaps one with a slightly menacing Santa on the cover, hinting that not all is merry and bright. Christmas Evil (or You Better Watch Out, as some faded VHS boxes proclaimed) isn't your typical holiday fare. It doesn't offer comfort or joy, but rather plunges us into the fractured psyche of a man consumed by the very spirit he cherishes, twisting festive cheer into something deeply unsettling. This isn't just a slasher flick with a Santa suit; it's a grimy, disturbing character study that lingers long after the fake snow settles.

When Cheer Curdles

The film introduces us to Harry Stadling, a toy factory worker obsessed with Christmas. This isn't just enthusiasm; it's a profound, almost pathological devotion rooted in a traumatic childhood glimpse of "Santa" behaving badly. As an adult, Harry meticulously monitors the neighborhood children, keeping detailed ledgers of who's naughty and nice. He lives and breathes Christmas, his apartment a shrine to the season, his life dedicated to upholding its purest ideals. But when the disillusionment of the adult world – corporate greed at the toy factory, cynicism from colleagues, the general lack of true Christmas spirit – becomes too much, Harry snaps. Donning a bespoke Santa suit, he embarks on a Yuletide journey that blurs the line between gift-giver and punisher, saint and psychopath.

A Portrait of Crumbling Santity

What makes Christmas Evil burrow under your skin isn't gore or jump scares, but the central performance by Brandon Maggart. He delivers something truly remarkable as Harry. There's a childlike vulnerability, a genuine belief in the magic of Christmas that makes his initial obsession almost pitiable. You see the hurt in his eyes when his dedication is mocked, the quiet desperation as he tries to embody the perfect Santa Claus. Yet, as his mental state deteriorates, Maggart seamlessly transitions into menace. It's not the cackling evil of a typical movie villain, but the chillingly calm, righteous fury of a true believer whose faith has been warped. His transformation feels disturbingly plausible, making the unfolding events all the more unnerving. Supporting players like Jeffrey DeMunn (later recognizable from The Shawshank Redemption and The Walking Dead) as Harry's concerned brother Phillip add a layer of grounded reality that contrasts sharply with Harry's increasingly bizarre behaviour.

Director Lewis Jackson, who also penned the script, crafts a film steeped in a peculiar kind of dread. The atmosphere isn't one of outright terror, but of pervasive wrongness. Cheerful Christmas decorations clash with the grim realities of late 70s/early 80s New York suburbia. The toy factory sequences feel genuinely soul-crushing, highlighting the commercialization Harry despises. Jackson uses slow pacing not to bore, but to build Harry's isolation and simmering resentment. The score often opts for distorted carols or unsettling silence, amplifying the psychological tension rather than telegraphing shocks. It’s this commitment to character and mood over cheap thrills that elevates Christmas Evil beyond its lurid premise.

The Cult of Christmas Past

Finding this tape back in the day felt like uncovering forbidden knowledge. It wasn't a mainstream hit; Christmas Evil famously flopped on its initial release, likely confusing audiences expecting a straightforward Santa slasher like Silent Night, Deadly Night which would arrive a few years later. Its journey to cult classic status was a slow burn, fueled by late-night TV airings and word-of-mouth among genre fans who recognized its unique, unsettling charm. Perhaps the most famous endorsement came from none other than John Waters, the Pope of Trash himself, who declared it the greatest Christmas film ever made. That tells you something about the specific brand of transgressive weirdness this film taps into. It's a Christmas movie for people who find the forced cheer of the season inherently suspicious.

The practical elements, like Harry’s meticulously crafted Santa suit and the almost documentary-style feel of some scenes, lend it a gritty realism that holds up surprisingly well. There’s an authenticity to its portrayal of mundane life juxtaposed with Harry’s fantasy world that feels very much of its time – a snapshot of disillusionment lurking beneath the suburban surface. Doesn't that slow descent into madness, fueled by societal hypocrisy, still feel disturbingly relevant?

Rating & Final Reflection

Christmas Evil isn't perfect. Its pacing can feel deliberately slow, and those expecting a high body count might be disappointed. It occupies a strange space between character drama, psychological thriller, and holiday horror. But its power lies in its unsettling ambiguity and Brandon Maggart's unforgettable performance. It dares to suggest that the pressure to be perpetually merry can itself create monsters.

Rating: 7.5/10

Justification: This score reflects the film's undeniable effectiveness as a creepy, character-driven piece and its well-deserved cult status. Brandon Maggart's central performance is exceptional, and the film creates a unique, lingering sense of unease. It loses points for pacing issues that might deter some viewers and for not fully satisfying expectations of a conventional horror film, but its psychological depth and atmospheric grit make it a standout oddity from the era.

For those seeking a different kind of chill this holiday season, or anyone fascinated by the darker corners of 80s cinema, digging up Christmas Evil is well worth the effort. It’s a bizarre, strangely poignant, and genuinely disturbing piece of misfit cinema that proves Santa Claus isn't always coming to town for the reasons you think. It remains a potent reminder that sometimes the most frightening monsters are the ones convinced they're doing the right thing.