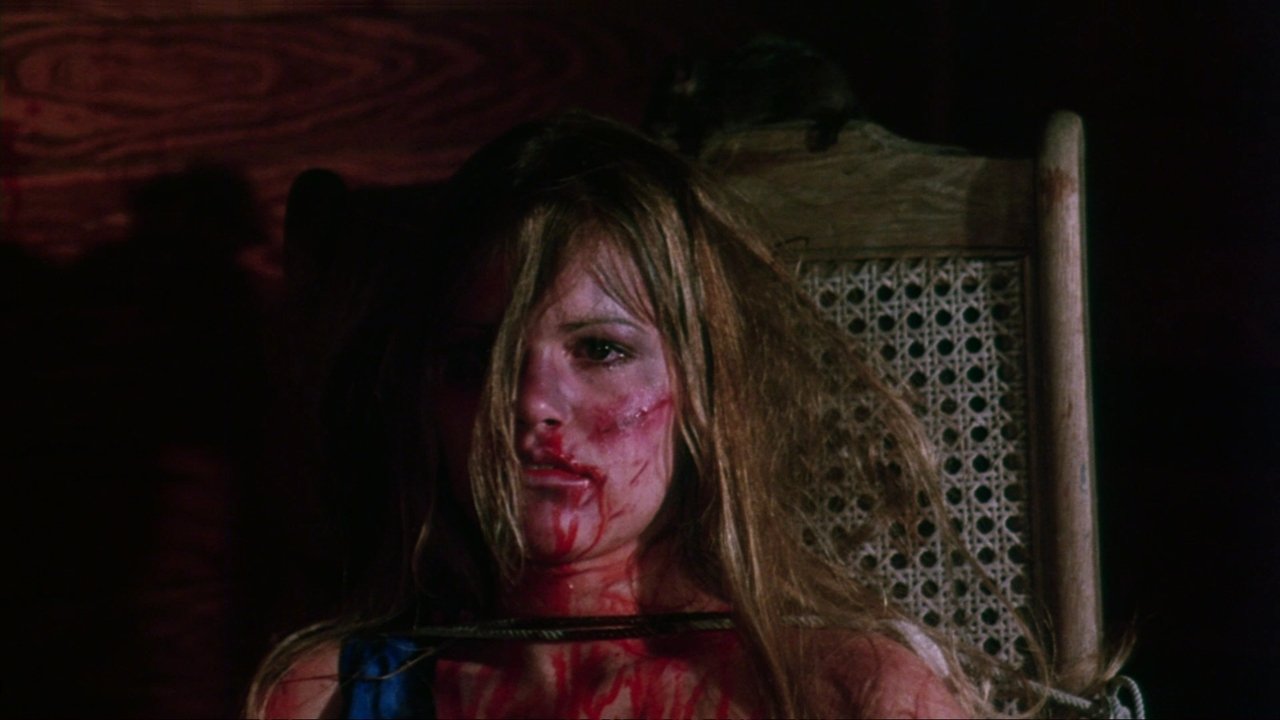

The flickering static clears, the tracking lines wobble for a second, and then… that face. Twisted in a rictus of primal terror, reflected in the glint of something sharp. Some films arrive quietly, others detonate on impact. Romano Scavolini’s 1981 descent into psychosis, Nightmare (or, perhaps more aptly, Nightmares in a Damaged Brain), belongs firmly in the latter category. This wasn't just another slasher cluttering the shelves of the local video den; this felt dangerous, forbidden fruit plucked from the darkest corner of the horror section. Watching it felt like an act of transgression.

A Mind Unraveling in the Florida Sun

Forget carefully constructed suspense. Nightmare plunges you headfirst into the fractured consciousness of George Tatum (Baird Stafford), a man recently discharged from institutional care where his experimental therapy involved being force-fed his most traumatic childhood memories. Released back into the simmering heat of Florida, Tatum is less a man cured and more a psychological time bomb with a rapidly shortening fuse. Stafford’s performance is key here; wide-eyed, sweating, perpetually on the verge of snapping, he embodies a raw, uncomfortable portrait of mental disintegration that goes beyond typical slasher villainy. It’s not a subtle portrayal, but it’s undeniably potent, anchoring the film’s descent into brutality. Scavolini, who also penned the script, seems less interested in why Tatum snaps and more fascinated by the visceral how. The narrative follows Tatum as he stalks a family – a mother and her kids – seemingly chosen at random, intercutting his increasingly violent actions with flashbacks to the primal scene trauma that haunts him. It’s a grim, relentless structure that offers little respite.

The Legend of the Gore

Let’s be blunt: the reason Nightmare became infamous, the reason it earned a coveted spot on the UK's notorious "video nasty" list and faced censorship battles worldwide, is its unflinching, stomach-churning gore. The practical effects, often the subject of behind-the-scenes legend and controversy, are shockingly explicit, even by today's standards. Remember seeing that axe connect with flesh, the arterial spray painting the walls? It felt disturbingly real on those fuzzy CRT screens. The effects were credited pseudonymously to C.J. Cooke, but the name whispered in connection was none other than gore maestro Tom Savini (Dawn of the Dead (1978), Friday the 13th (1980)). Savini's actual involvement remains murky; he's alternately claimed mere consultancy, partial work, or distanced himself entirely, while the producers undeniably used his reputation as a major selling point. This very ambiguity became part of the film's dark allure – was this really Savini's work, pushed to an extreme he later regretted? Regardless of the exact hand guiding the latex and Karo syrup, the impact was undeniable. These weren't jump scares; they were lingering moments of visceral violation designed to make you squirm, to genuinely revolt you. The infamous decapitation, the axe-in-the-pillow – these scenes burned themselves into the minds of anyone brave (or foolish) enough to rent the tape, often housed in those oversized clamshell cases that promised something truly illicit.

Beyond the Bloodshed: Atmosphere and Notoriety

While the splatter takes center stage, Scavolini does manage to conjure a genuinely sleazy, oppressive atmosphere. The Florida locations feel sweaty and decaying, mirroring Tatum's internal state. The low budget ($650,000, translating to roughly $2.2 million today) contributes to a raw, unpolished feel that somehow enhances the griminess. There’s a nihilistic streak running through Nightmare that sets it apart from some of its slicker contemporaries. It doesn’t wink at the audience; it stares, unblinking, into the abyss. This commitment to unpleasantness is arguably its defining characteristic, the source of both its condemnation and its enduring cult fascination. Stories circulated about Scavolini himself facing legal troubles, even arrest in New York, supposedly tied to the film's extreme content, further cementing its hazardous reputation. Whether entirely true or embellished legend, it fed the narrative: this was a film someone tried to stop you from seeing.

A Relic of Raw Horror

Is Nightmare a conventionally "good" film? Probably not. Its pacing can drag between the set pieces, the supporting characters are thinly sketched, and its exploration of mental illness is purely exploitative. Yet, its power as a piece of raw, confrontational horror cinema is undeniable. It represents a specific moment in time – the pre-cert video boom, where films this extreme could bypass traditional gatekeepers and land directly in viewers' homes, sparking moral panic and censorship crackdowns. It pushed boundaries, deliberately and unapologetically, and its legend was built as much on the reaction it provoked as on the film itself. Doesn't that central performance from Stafford still feel genuinely unnerving, even now?

VHS Heaven Rating: 6/10

Justification: Nightmare earns its points for sheer audacity, its landmark status in the "video nasty" saga, Baird Stafford's committedly unhinged performance, and practical gore effects that remain shockingly effective (and controversial). It successfully creates a palpably grimy and disturbing atmosphere. However, it loses points for its often sluggish pacing between the shocks, underdeveloped supporting characters, and its purely exploitative handling of sensitive themes. It's a raw, brutal, and historically significant piece of grindhouse horror, but far from a polished masterpiece.

Final Thought: A grimy, unforgettable relic from the wild west of home video, Nightmare is less a film you enjoy and more one you endure and survive. It’s a potent reminder of a time when horror felt genuinely dangerous, capable of shocking not just with blood, but with its bleak, nihilistic view of a mind utterly, terrifyingly broken.