Some nightmares don't end when you wake up. They bleed into the daylight, cold and sharp, leaving psychic shrapnel behind. 1982's The Sender doesn't just depict nightmares; it weaponizes them, crafting a chilling exploration of projected trauma that burrows under your skin long after the credits roll and the VCR clicks off. Forget jump scares; this is a film that builds its terror brick by insidious brick, leaving you questioning the very fabric of the reality presented on screen. It arrived quietly, without the fanfare of its slasher brethren, but its unsettling power feels uniquely potent, especially when revisited through the hazy glow of memory and magnetic tape.

Whispers from Ward 83

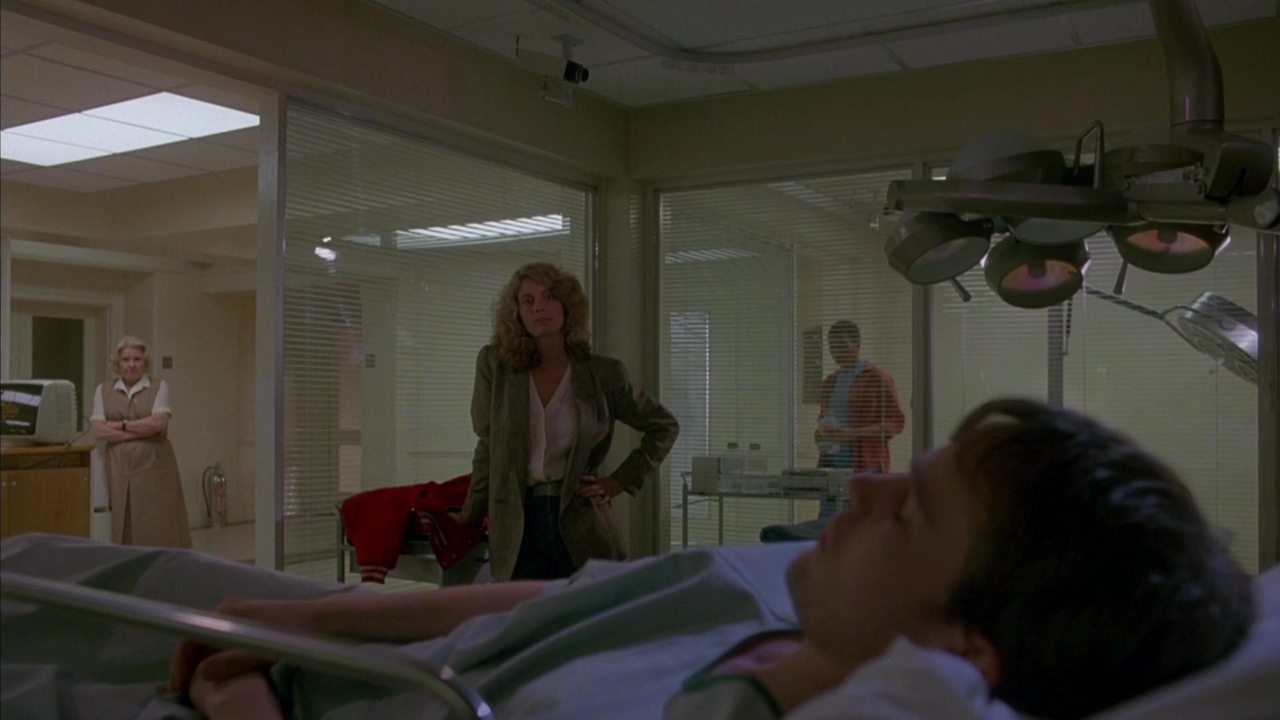

The film opens with deliberate ambiguity. A young man, hauntingly portrayed by a debuting Željko Ivanek, walks into a lake, a picture of serene self-destruction. Pulled out and admitted to a psychiatric hospital as John Doe #83, he initially seems catatonic, unresponsive. But soon, his assigned psychiatrist, Dr. Gail Farmer (Kathryn Harrold), begins experiencing vivid, terrifying hallucinations – his nightmares made real. Insects crawl from nowhere, mirrors bleed, rats swarm – the waking world becomes infected by his subconscious terrors. The Sender quickly establishes its unnerving premise: this isn't just about observing madness; it's about catching it.

Director Roger Christian, fresh off directing the visually stunning short Black Angel (1980) often paired with The Empire Strikes Back and having earned his stripes (and an Oscar) doing set decoration for Star Wars (1977) and working on Alien (1979), brings a distinct visual sensibility. The sterile, institutional setting of the hospital – parts of which were filmed at the genuinely imposing Graylingwell Hospital, a former psychiatric facility in England – becomes a character itself. It's a place of supposed healing that feels perpetually on the verge of collapse into unreality. Christian masterfully contrasts the clinical daytime environment with the visceral intrusions of the Sender's projected horrors.

Dreams Made Flesh

What truly sets The Sender apart, especially within the early 80s horror landscape, is its focus on psychological dread over graphic violence. The scares stem from the violation of Farmer's reality, the impossibility of what she's seeing. The practical effects used to bring these nightmares to life retain a disturbing tangibility. The scene with the bleeding bathroom mirror or the sudden infestation of insects feels viscerally wrong, tapping into primal phobias. There’s a story that the intense electroconvulsive therapy scene caused a stir with the ratings board, a testament to its raw, uncomfortable power even back then. These weren't CGI apparitions; they felt grounded, physical, making the psychic bleed-through all the more disturbing. Remember how those tangible effects felt so much more real on grainy VHS?

The film owes much of its unsettling atmosphere to Trevor Jones's score. Known for his evocative work on fantasies like Excalibur (1981) and The Dark Crystal (1982), Jones provides a soundtrack that is both melancholic and menacing, perfectly complementing the film’s exploration of fractured minds and emotional turmoil. It avoids cheap stingers, instead opting for a pervasive sense of unease that mirrors the creeping dread experienced by Dr. Farmer.

A Mind Divided

At its core, The Sender is a tragedy wrapped in a horror film. Željko Ivanek gives a remarkable debut performance, balancing the character's destructive power with a palpable vulnerability. He’s not a monster, but a deeply damaged individual whose uncontrolled abilities are born from trauma, specifically linked to his estranged, religiously zealous mother, chillingly played by Shirley Knight. Kathryn Harrold provides the empathetic anchor, her journey from skeptical professional to unwilling participant in his psychic turmoil drawing the audience into the nightmare. Their interactions form the emotional crux of the film, exploring themes of empathy, connection, and the devastating impact of unresolved pain.

It’s often noted, and feels distinctly plausible, that the film's central conceit – nightmares manifesting physically and affecting others – pre-dates and perhaps even influenced Wes Craven's A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984). While Freddy Krueger became the pop culture icon, The Sender offers a more introspective, somber take on dream manipulation, grounded in psychological realism rather than supernatural boogeymen. Even Stephen King reportedly sang its praises, recognizing its unique and unsettling vision.

Rediscovering a Lost Signal

The Sender wasn't a blockbuster. It arrived, flickered briefly in theaters, and then found its true home on video store shelves, becoming one of those cult discoveries passed between horror fans like a secret. I distinctly remember the stark, intriguing VHS cover catching my eye in the horror section, promising something different from the usual masked killers. It delivered. Rewatching it now, its deliberate pacing might test some viewers accustomed to faster cuts, but its mood and intelligence hold up remarkably well. It’s a film that trusts its audience, preferring to unsettle rather than simply startle.

It stands as a testament to a period where studios were still willing to take chances on atmospheric, character-driven horror that didn't necessarily fit the dominant slasher mold. It's a film that asks more questions than it answers, leaving a lingering chill that speaks to the fragility of the mind and the enduring power of nightmares.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's exceptional atmosphere, strong central performances, unsettling practical effects, and intelligent premise that sets it apart from much of its early 80s horror brethren. It successfully creates a pervasive sense of dread and psychological disturbance, bolstered by a haunting score and effective direction. While its pacing might be slower than some prefer, its thoughtful approach to horror and its lasting unsettling quality make it a genuine cult classic worthy of its 8 rating. The Sender remains a potent dose of psychological unease, a reminder that sometimes the most terrifying place isn't a haunted house, but the landscape of the human mind. Doesn't that central idea still feel disturbingly resonant?