### Streets Paved with Bad Intentions

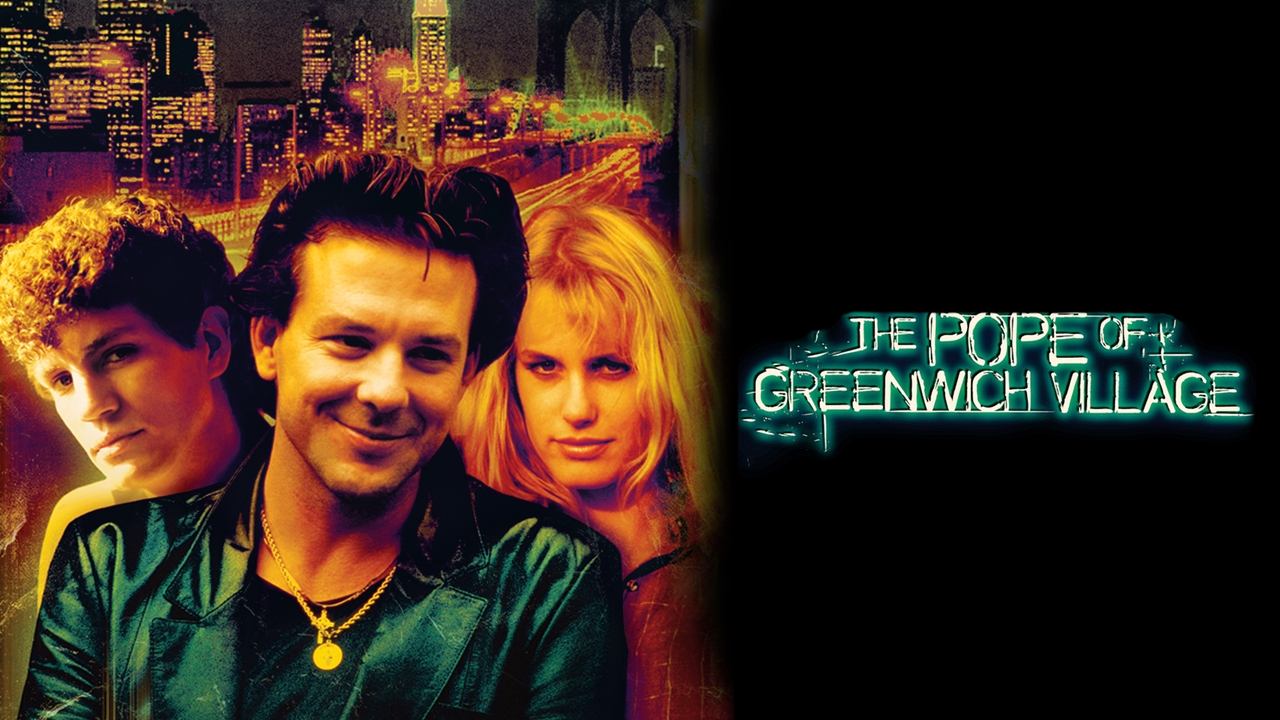

What exactly does it mean to be "The Pope of Greenwich Village"? The title hangs over Stuart Rosenberg's 1984 film like a question mark etched in cigar smoke against a grimy New York skyline. It suggests power, reverence, perhaps even a touch of the sacred. But spend ninety minutes with cousins Charlie Moran (Mickey Rourke) and Paulie (Eric Roberts), and you realize the title, much like Paulie's ambitions, is built on shaky foundations, a small-time crown worn in a kingdom of cracked pavement and desperate dreams. This isn't about grandeur; it's about the swagger and delusion needed to survive when you're perpetually chasing the next big score that never quite lands.

A Slice of Gritty New York Life

At its heart, The Pope of Greenwich Village isn't a complex heist movie, though a spectacularly ill-conceived robbery provides the catalyst. It's a character study, a dive into the symbiotic, often toxic relationship between two men bound by blood and bad choices. Charlie, played with a soulful weariness by Mickey Rourke (just before his meteoric rise with 9½ Weeks), is the relatively sensible one. He has a girlfriend, Diane (Daryl Hannah, radiating earnestness), aspirations of owning a restaurant, and a conscience that Paulie constantly tries to override. Paulie, embodied with explosive, manic energy by Eric Roberts, is the dreamer, the schemer, the guy whose reach always exceeds his grasp, usually pulling Charlie down with him. He’s the headwaiter who thinks he's a kingpin, convinced his ship is always just about to come in. Their dynamic crackles with an authenticity that feels less like acting and more like eavesdropping on years of shared history, arguments, and misguided loyalty.

Performance Powerhouse

The film truly belongs to Rourke and Roberts. Their chemistry is undeniable, fueled, according to some production tales, by a degree of real-life friction that translated into palpable on-screen tension. Rourke’s Charlie is all simmering frustration and reluctant affection; you see the internal battle in his eyes as he’s drawn into Paulie’s latest disaster. Roberts, conversely, is a force of nature – loud, pathetic, dangerously optimistic, and utterly convincing as a man blind to his own limitations. It's a performance that teeters on the edge of caricature but finds its grounding in genuine desperation. Watching them together is like watching a slow-motion car crash you can't look away from – you know it's doomed, but the interplay is mesmerizing.

It wasn't just the leads who shone. The supporting cast felt like they’d genuinely walked off the streets of Little Italy. Burt Young brings his usual world-weary menace as the local mob boss "Bed Bug" Eddie Grant. And then there’s Geraldine Page, who earned a well-deserved Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress as Mrs. Ritter, the grieving, vengeful mother of a bent cop caught up in the cousins' mess. Her scenes are brief but absolutely chilling, injecting a dose of harsh reality into the proceedings.

Behind the Neighbourhood Curtain

Getting The Pope of Greenwich Village made wasn't straightforward. Director Stuart Rosenberg, known for gritty classics like Cool Hand Luke (1967), stepped in after the original director, Michael Cimino, was reportedly removed. Given Cimino’s reputation following the infamous Heaven's Gate (1980), perhaps the studio wanted a steadier hand for this adaptation of Vincent Patrick's novel (Patrick also wrote the screenplay). The film, shot on location, breathes the authentic air of 1980s New York – the steam rising from grates, the cramped apartments, the bustling street life. It cost around $8 million to make but sadly didn't ignite the box office, grossing under $7 million domestically. Yet, like so many films we cherish from that era, it found its audience later, becoming a solid cult favorite on VHS – that well-worn tape was probably a fixture in many rental stores next to other NYC tales like Mean Streets or After Hours.

One unforgettable slice of gritty realism involves Paulie losing a thumb – a moment handled with stark, unglamorous finality that sticks with you. It’s a blunt reminder of the stakes, cutting through the sometimes-comedic absurdity of their situation. The dialogue, drawn heavily from Patrick's novel, crackles with authentic street slang and rhythm, adding immeasurably to the film's lived-in feel.

Loyalty, Delusion, and the Price of Friendship

What lingers long after the credits roll isn't necessarily the plot, but the exploration of loyalty and its limits. How far do you go for family, especially when that family is actively sabotaging your life? Charlie’s internal conflict – his desire for a better life clashing with his ingrained sense of obligation to the hopelessly flawed Paulie – feels deeply human. Does Paulie’s unwavering (if misguided) belief in himself make him a tragic figure or just a fool? The film doesn’t offer easy answers, letting the ambiguity hang in the air like the scent of marinara sauce and exhaust fumes. It captures that specific 80s blend of cynicism and aspiration, where the American Dream felt both tantalizingly close and impossibly rigged for guys like Charlie and Paulie.

Watching it again now, maybe on a flatscreen instead of the old CRT behemoth, there's a definite warmth despite the grit. It's the warmth of recognition – of flawed characters trying to get by, of a specific time and place captured with honesty, and of powerhouse actors absolutely owning their roles. My own tape got chewed up years ago, but the memory of their performances hasn't faded.

Rating: 8/10

The Pope of Greenwich Village earns its 8/10 through sheer force of character and atmosphere. While the plot follows familiar small-time crime beats, the central performances by Rourke and Roberts are electrifying, creating an unforgettable, volatile dynamic. Supported by a stellar cast and Rosenberg's assured, unflashy direction, the film offers an authentic, bittersweet taste of 80s New York street life that resonates long after the screen fades to black.