The rain lashes against the windshield, wipers struggling to clear a path through the deluge on a lonely stretch of West Texas highway. Inside, young Jim Halsey (C. Thomas Howell) is fighting sleep, delivering a car from Chicago to San Diego. Then, a figure emerges from the downpour, thumb outstretched. A moment's hesitation, a decision made in the weary solitude of the road, and the nightmare begins. This isn't just a ride gone wrong; this is The Hitcher (1986), and it plunges you into a maelstrom of senseless, terrifying pursuit that feels disturbingly real, even decades later.

The Phantom of the Highway

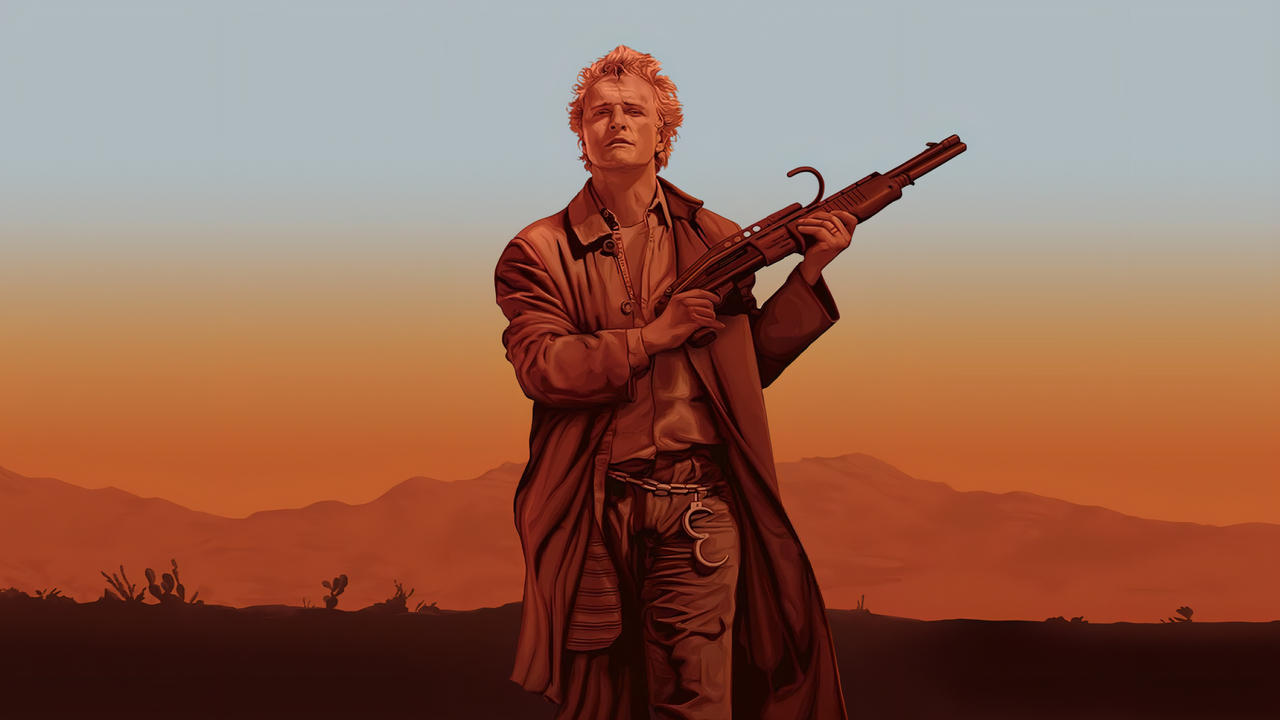

Forget jump scares. The Hitcher's power lies in its suffocating atmosphere and the chilling enigma of its antagonist. John Ryder, brought to life with unnerving intensity by the late, great Rutger Hauer, isn't just a killer; he's an almost supernatural force of malevolence, a void staring back from the passenger seat. Hauer, fresh off his iconic role as Roy Batty in Blade Runner (1982), reportedly approached Ryder with a terrifying commitment, sometimes staying in character between takes, genuinely unsettling his co-star Howell. His initial lines, delivered with a calm detachment that belies the horror to come, still send shivers down the spine:

> "I want you to stop me."

It’s a plea wrapped in a threat, setting the stage for a relentless cat-and-mouse game across desolate landscapes. Director Robert Harmon, making his feature debut, masterfully uses the vast, empty spaces of the desert not as freedom, but as an inescapable prison. The sun-bleached gas stations and dusty diners offer no refuge, only temporary stages for Ryder's escalating torment of Halsey.

A Descent into Chaos

What makes The Hitcher burrow under your skin is how it implicates Halsey, twisting him from innocent victim to hunted fugitive. Ryder doesn't just want to kill Jim; he wants to break him, to frame him, to perhaps even pass on his mantle of nihilistic destruction. C. Thomas Howell, known then for lighter fare like The Outsiders (1983), delivers a compelling performance, charting Halsey's desperate spiral from naive kid to a hardened survivor pushed to the absolute edge. You feel his panic, his disbelief, his dawning horror as Ryder reappears with impossible frequency, always one step ahead, leaving carnage in his wake. The script, penned by Eric Red (who would later write and direct Cohen and Tate (1988) and write Near Dark (1987)), was famously inspired by The Doors' "Riders on the Storm" and was initially even more graphic, pared down slightly but losing none of its visceral punch. Red envisioned a story where the highway itself felt like a malevolent entity.

Stunts, Tension, and That Scene

The film boasts some genuinely impressive practical stunt work for its era, particularly the sequences involving trucks and cars. The sense of weight and impact feels terrifyingly authentic – metal shreds, glass shatters, and vehicles become instruments of destruction. Harmon orchestrates these moments with brutal efficiency, amplifying the tension rather than merely providing spectacle. Reportedly, some of the close calls during filming were genuinely nerve-wracking for the crew, adding another layer to the film's palpable sense of danger.

And then there’s that scene. Spoiler Alert! The sequence involving Nash (Jennifer Jason Leigh, who brought a welcome spark of defiance and warmth) and the two trucks remains one of the most shocking and debated moments in 80s thriller cinema. It’s audacious, cruel, and utterly unforgettable, pushing the boundaries of mainstream horror at the time. It's a moment that seals the film's bleak worldview, cementing Ryder's status as an avatar of pure, motiveless evil. Leigh’s character provides a brief, crucial glimmer of hope and connection for Halsey, making its extinguishment all the more devastating.

Echoes in the Dark

The Hitcher wasn't a massive box office smash upon release (grossing around $6 million on a $5.8 million budget), and critical reception was somewhat divided, with some finding its nihilism off-putting. Yet, its influence lingered. It tapped into a primal fear – the vulnerability of the open road, the stranger in our midst – and amplified it into an existential horror show. Its DNA can be seen in countless road thrillers that followed. It’s a film that feels leaner, meaner, and more psychologically unsettling than many of its contemporaries. The desolate cinematography by John Seale and the haunting score by Mark Isham are inseparable from its power, creating a soundscape of dread that perfectly complements the visuals. Hauer’s performance remains legendary; he famously refused to reveal Ryder’s backstory, believing the character was more terrifying as an unknown quantity, a force of nature rather than a man with a motive.

VHS Heaven Rating: 9/10

This score reflects The Hitcher's masterful execution of suspense, its suffocating atmosphere, and Rutger Hauer's truly iconic performance. It’s relentless, unnerving, and brilliantly crafted, leveraging its desolate setting and practical effects to maximum impact. While its bleakness and brutal violence might not be for everyone, and some plot logistics might stretch credulity if examined too closely, its power as a pure exercise in terror is undeniable. It loses a single point perhaps only for the sheer nihilism that might leave some viewers cold rather than thrilled, but its craft is impeccable.

The Hitcher is more than just an effective thriller; it’s a primal scream echoing from the heart of the 80s, a stark reminder that sometimes, the most terrifying monsters are the ones we willingly let into our cars. It’s the kind of film that, once seen, makes you think twice about ever picking up a stranger on a lonely highway again. Doesn't that chill still linger?