The darkness presses in. Not just the gloom of the grand opera house, but the suffocating dread that Dario Argento orchestrates with sadistic precision in his 1987 Giallo masterpiece, Opera. Forget jump scares; this is about sustained, almost unbearable tension, a feeling amplified by the memory of watching it on a flickering CRT screen late at night, the volume low enough not to wake anyone, the grainy VHS visuals somehow making the horror feel even more immediate, more invasively real. Opera isn't just watched; it's endured, in the most compelling way possible.

A Symphony of Terror

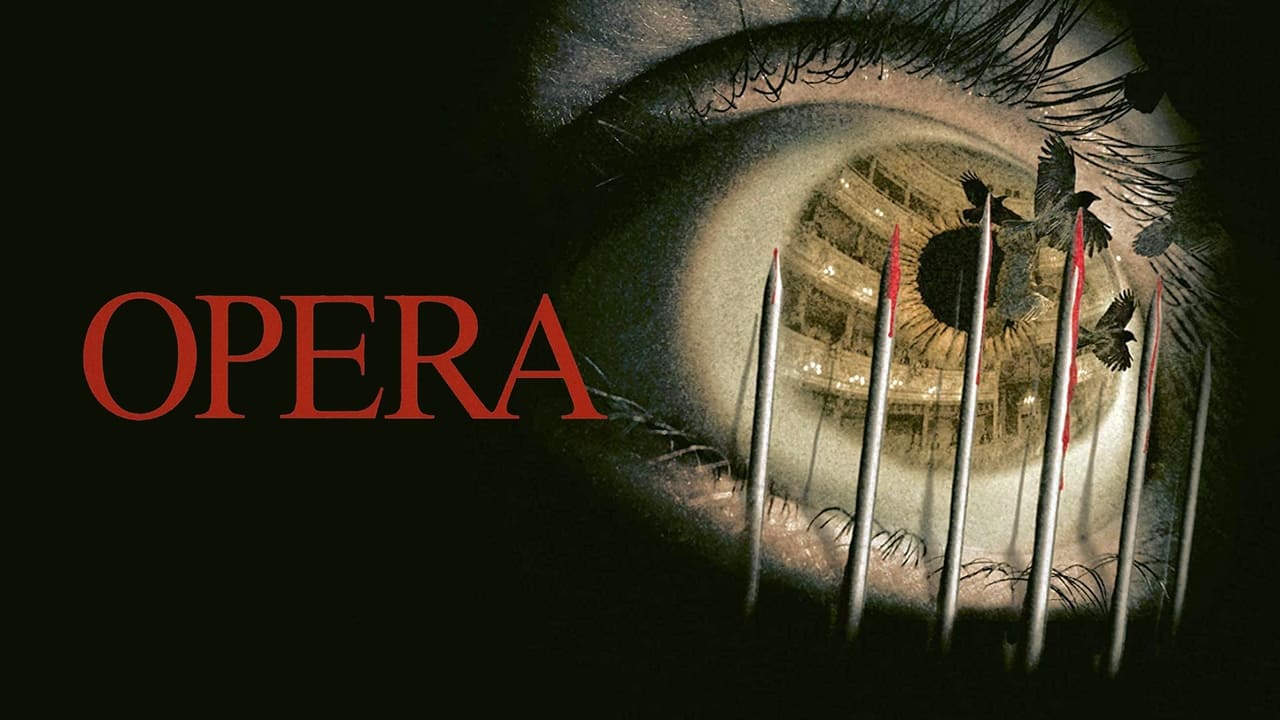

The premise is pure Giallo, yet elevated by Argento’s feverish style. Betty (Cristina Marsillach), a young understudy soprano, is thrust into the lead role of Verdi's Macbeth when the prima donna meets a suspicious accident. It’s the role of a lifetime, but it comes tethered to a nightmare. A black-gloved killer, obsessed with Betty, begins a spree of gruesome murders, forcing her to witness his atrocities by taping rows of needles beneath her eyelids, preventing her from closing them. Does that central, horrifying image still send a shiver down your spine? It’s a visceral hook that Argento uses to trap not just Betty, but the viewer, making us complicit observers in the unfolding carnage. The sheer audacity of that conceit remains stunning.

Argento Unleashed

By 1987, Dario Argento, the maestro behind Suspiria (1977) and Tenebrae (1982), was at the height of his stylistic powers, and Opera feels like a culmination. Reportedly his most expensive film at the time, every lira feels splashed across the screen. The cavernous opera house becomes a character itself – a labyrinth of opulent corridors, shadowy recesses, and dizzying heights. Argento’s camera rarely sits still; it prowls, glides, and swoops with predatory grace. The famous raven's-eye-view shots, achieved with complex Steadicam work navigating the vast theatre, weren't just technical showboating; they created a genuinely unsettling, almost supernatural perspective on the killings, adding to the film's dreamlike, disoriented quality. This wasn't just point-and-shoot; this was filmmaking as a kinetic assault.

Behind the Velvet Curtain

The production itself seemed steeped in the kind of dark legend that clings to Argento’s work. Dubbed "Terror at the Opera" during production, the film was notoriously plagued by misfortune, feeding into the idea of an "Argento curse." His own father passed away during filming, actor Ian Charleson (playing the intense director Marco, in one of his final, poignant roles before tragically succumbing to AIDS) faced his diagnosis shortly after, and original star Vanessa Redgrave reportedly dropped out. There were even persistent rumors of friction between Argento and his young lead, Cristina Marsillach, whose demanding role required her to convey sheer terror often while immobilized by the killer's horrific device. You can almost feel that tension bleeding onto the screen, adding another layer to Betty's palpable fear. These weren't just challenges; they became part of the film's grim tapestry.

The practical effects, while perhaps showing their seams today compared to CGI, retain a brutal, tactile power. Argento never shied away from graphic violence, and Opera features some genuinely stomach-churning sequences. That infamous needle device, reportedly achieved with lightweight materials carefully positioned, looks agonizingly real, forcing a sympathetic wince from anyone watching. It’s the kind of tangible horror that defined the best of 80s genre filmmaking – you felt it could happen.

Discordant Notes, Lasting Resonance

The soundtrack is another signature Argento element: a deliberately jarring mix of soaring Verdi arias and pounding heavy metal tracks from artists like Bill Wyman and Terry Taylor, alongside collaborator Claudio Simonetti's synthesizers. This clash might feel uneven to some, but it perfectly encapsulates the film's mood – high art violently interrupted by primal savagery. It keeps the audience perpetually off-balance, unsure whether to be awed or appalled.

While Cristina Marsillach carries the weight of the terror effectively, and Ian Charleson brings a simmering intensity, the film belongs to Argento's vision. It’s less about deep character arcs and more about sensory overload and meticulously crafted suspense sequences. The plot, like many Gialli, takes some logic-defying turns, particularly towards the climax, but the ride is so visually stunning and viscerally gripping that you forgive its narrative eccentricities. This is nightmare logic, rendered with operatic grandeur.

***

VHS HEAVEN RATING: 9/10

Opera stands as one of Dario Argento's most ambitious and technically dazzling works, arguably the last great flourish of his classic Giallo period. The sheer audacity of its central conceit, the breathtaking camerawork, the unsettling atmosphere, and the unflinching violence create an unforgettable experience. While the narrative can be uneven and the acting occasionally subordinate to the spectacle, the film's power to disturb and mesmerize remains undiminished. It justifies its near-perfect score through its masterful control of tension, its iconic imagery (those needles!), and its status as a high-water mark for stylish, brutal 80s horror. For fans of Argento, Giallo, or simply visually stunning, psychologically taxing horror, Opera is essential viewing – a performance you're forced to watch, long after the tape has stopped rolling.