He builds a new life with the methodical precision of someone assembling a model kit, piece by perfect piece. A charming smile, a stable job, a ready-made family. But look closer – peer into those unnervingly calm eyes – and you see the terrifying truth: the pieces don't quite fit, and the glue holding them together is starting to crack. This is the cold, creeping dread at the heart of 1987's The Stepfather, a film that burrowed under the skin far more effectively than many of its gorier contemporaries, leaving a chill that lingered long after the VCR clicked off.

Beneath the Suburban Veneer

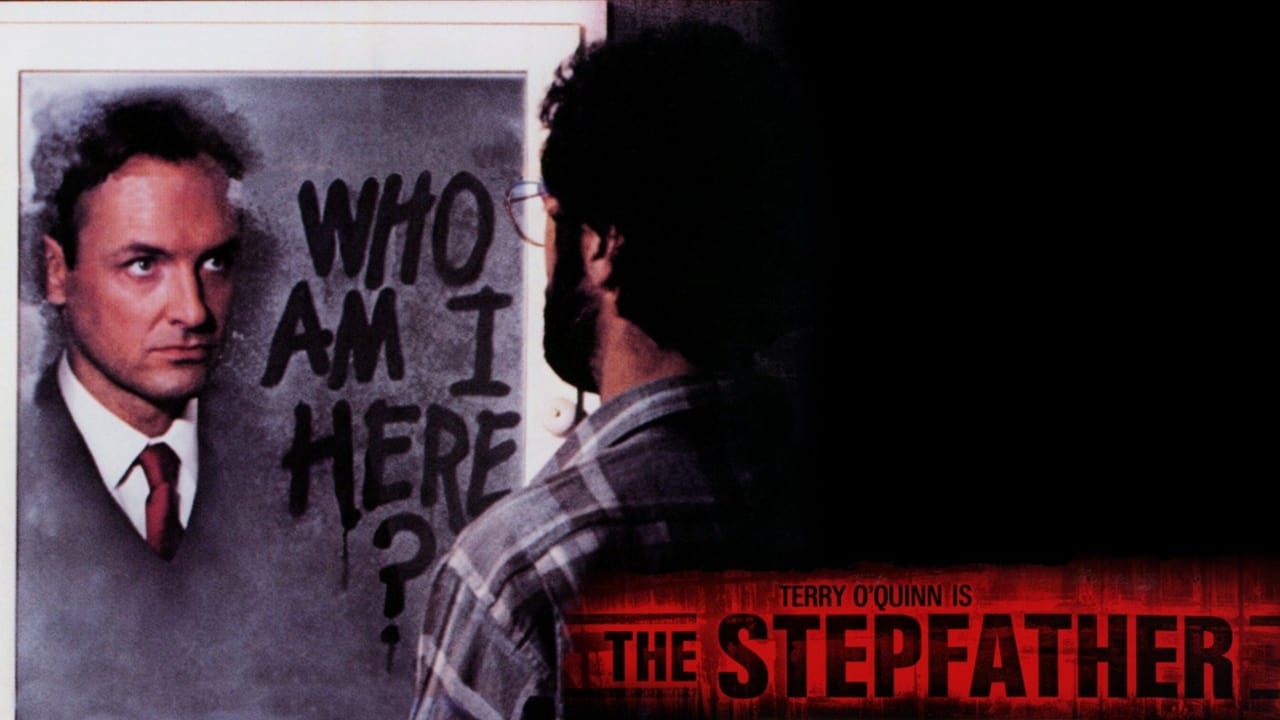

Forget masked slashers lurking in the woods. The monster here, Jerry Blake, lives right inside the house. Embodied with iconic, bone-chilling perfection by Terry O'Quinn (years before he’d find himself mysteriously stranded on an island in Lost), Jerry is the ultimate wolf in sheep's clothing. He craves the idyllic American family life with a desperate, pathological intensity. When reality inevitably falls short of his impossible Rockwellian fantasy – a messy room, a questioning stepdaughter, a hint of suspicion – his solution isn't compromise, it's erasure. Total, violent, and chillingly swift. O'Quinn’s performance is a masterclass in controlled menace; the way his cheerful facade can shatter in an instant, replaced by a terrifyingly blank rage, is the stuff of nightmares. Doesn't that sudden switch still feel disturbingly real?

The script, penned by renowned crime novelist Donald E. Westlake (based on a story he co-wrote), understood the power of suggestion and simmering tension. It had reportedly languished in development hell for years, a testament perhaps to how unsettling its core concept was. The story draws unsettling parallels to the real-life case of John List, a seemingly ordinary man who murdered his entire family in 1971 and started a new life elsewhere, evading capture for nearly two decades. This grounding in a potential reality elevates The Stepfather beyond simple exploitation; it taps into a primal fear about who we truly let into our lives. Westlake’s sharp dialogue and focus on character over cheap shocks give the film a disturbing plausibility.

Building the Unease

Director Joseph Ruben, who would later revisit domestic terror with 1991's Sleeping with the Enemy, crafts an atmosphere thick with suspicion. He uses the seemingly benign suburban setting – the neat houses, the green lawns – to amplify the horror. It’s the violation of this safe space that makes Jerry’s presence so profoundly disturbing. The tension builds not through jump scares, but through observation. We watch Stephanie (a strong performance by Jill Schoelen, a familiar face from 80s/90s genre fare like Popcorn and Cutting Class) gradually piece together the inconsistencies in her new stepfather’s story. Her dawning realization mirrors our own growing dread. We see the cracks widening, waiting for the inevitable explosion. Remember that basement scene? The way the careful control just evaporates? Pure, distilled tension.

The film benefited immensely from its eventual home on VHS and cable. While its initial theatrical run was modest (grossing around $2.5 million on a $4.5 million budget – that's about $6.8 million in today's money), it found its audience in late-night rentals and broadcasts. My own well-worn tape certainly got its share of plays. It became a word-of-mouth hit, precisely the kind of unsettling gem you’d discover tucked away on the thriller shelf at the local video store. Its success spawned sequels – the direct follow-up Stepfather II (1989) brought back O'Quinn, while Stepfather III (1992) was a TV movie affair with a different lead, and a glossy remake surfaced in 2009. None, however, quite captured the lightning-in-a-bottle chill of the original.

The Cracks Still Show

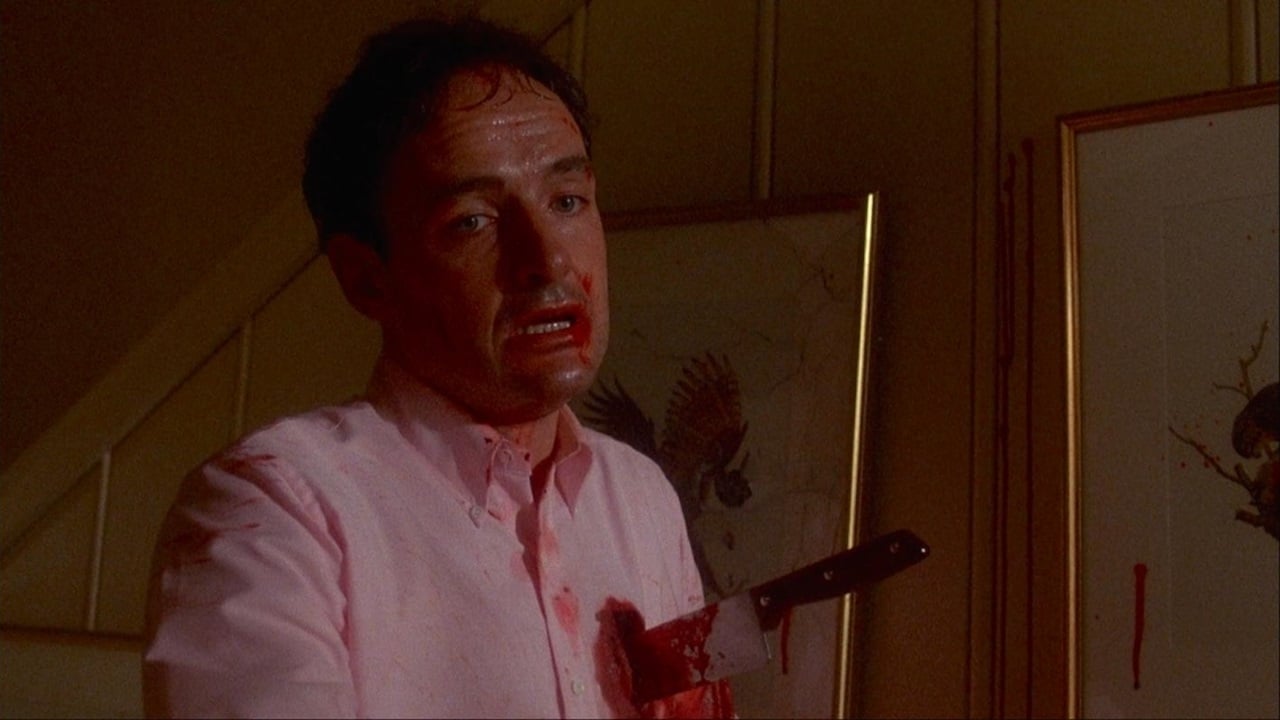

Watching The Stepfather today, it remains remarkably effective. O'Quinn’s commitment to the role was reportedly intense; stories circulated about him remaining deeply immersed in the character, aiming not for monstrousness but for the terrifying mindset of someone desperately pursuing a warped ideal, sometimes unsettling his co-stars in the process. This dedication bleeds through the screen. The practical effects, particularly in the more violent moments, have that visceral, pre-CGI impact that felt disturbingly tangible on those flickering CRT screens. The score by Patrick Moraz effectively underscores the shifting moods, from eerie calm to outright panic. Sure, some of the dialogue or fashion might scream 1987, but the core psychological horror feels timeless.

It’s a film that understands that the most terrifying monsters are often the ones who look just like us, hiding their darkness behind a practiced smile and a desire for everything to be just perfect.

VHS Heaven Rating: 9/10

This score is earned primarily through Terry O'Quinn's landmark performance, which remains one of the genre's most chillingly believable villains. The expertly crafted suspense, the unsettling atmosphere built by Joseph Ruben, and the sharp, psychologically astute script from Donald E. Westlake solidify its high standing. It loses a point perhaps only for some inevitable dating in minor elements, but its core power is undiminished.

The Stepfather isn't just a slasher film transposed to the suburbs; it's a deeply unnerving psychological thriller that perfectly captured a specific kind of Reagan-era anxiety lurking beneath the surface of the American Dream. It remains a potent reminder that sometimes, the most terrifying place isn't a dark forest or an abandoned asylum – it's home.