There's a certain kind of chill that settles in the air when obsession takes root, a quiet intensity that tightens around you like fine wire. It's this feeling that permeates Bob Rafelson's stylish 1987 thriller, Black Widow. Not the noisy desperation of a frantic chase, but the focused, almost intimate pursuit between two women locked in a psychological dance – one hunting, the other evading, both perhaps recognizing something unsettlingly familiar in the other. Forget your typical 80s action heroes; this was a different, altogether more subtle game.

The Moth and the Flame

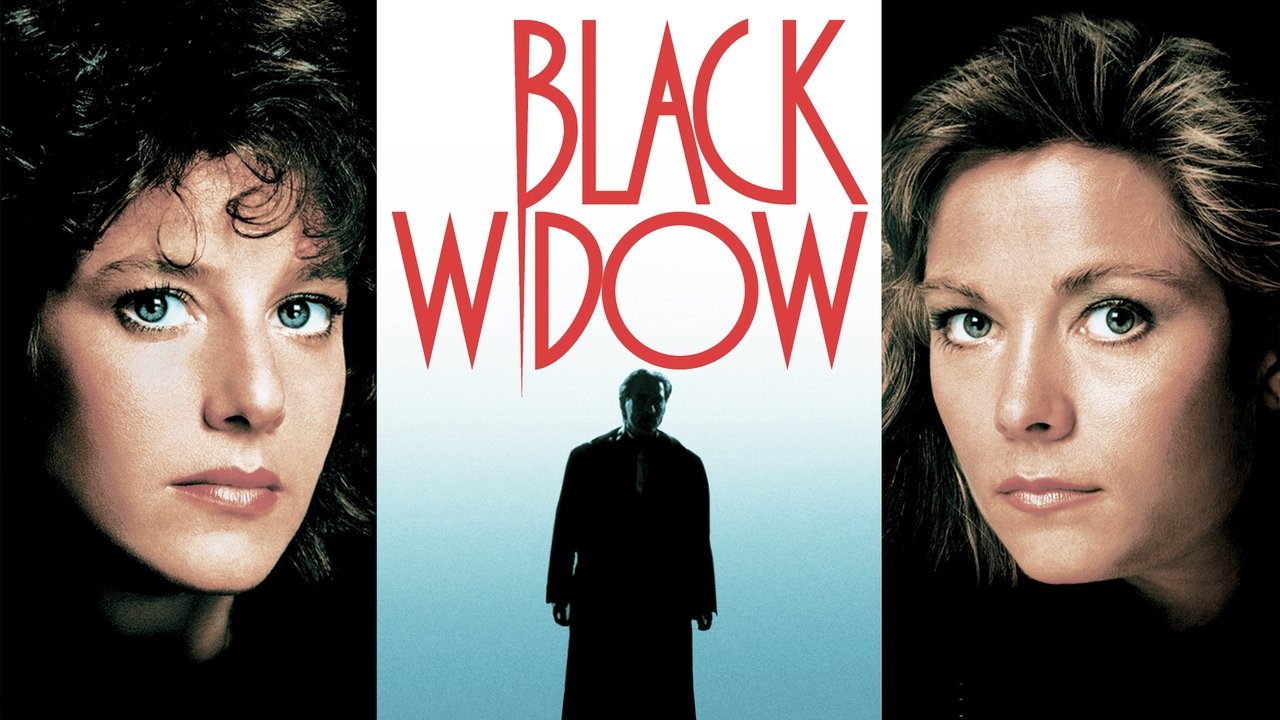

At its heart, Black Widow presents a compelling cat-and-mouse scenario. Alexandra "Alex" Barnes (Debra Winger) is a federal agent working a desk job in Washington D.C., intelligent but unassuming, almost blending into the background noise of bureaucracy. She begins to connect the dots between the deaths of several extremely wealthy, older men across the country. The common thread? Each was recently married to a beautiful, enigmatic younger woman who vanishes after inheriting a fortune, changing her identity like shedding skin. This chameleon is Catherine Petersen (Theresa Russell), a woman who operates with chilling precision and an allure that seems almost supernatural. What begins as a procedural investigation for Alex quickly spirals into something deeply personal, an obsession that pulls her out from behind the desk and into Catherine's glittering, dangerous world.

A Dance of Opposites

The film hinges entirely on the dynamic between its two leads, and thankfully, both Winger and Russell are mesmerizing. Winger, fresh off acclaimed roles in films like An Officer and a Gentleman (1982) and Terms of Endearment (1983), brings a fascinating blend of dogged determination and underlying vulnerability to Alex. You see the sharp mind working behind her often weary eyes, the frustration of being underestimated, and later, the magnetic pull Catherine exerts on her. There's a scene where Alex, trying to mimic Catherine's sophisticated style, looks almost painfully awkward – a small moment, but perfectly capturing her character's grounded reality clashing with the killer's effortless glamour. It’s a performance built on nuance, a quiet forcefulness that feels utterly authentic.

Opposite her, Theresa Russell is captivating as Catherine. Having worked extensively with then-husband Nicolas Roeg on complex films like Bad Timing (1980), Russell possessed an inherent mystique that serves the character perfectly. Catherine isn't just a killer; she's a void shaped into whatever her target desires. Russell shifts personas – the demure intellectual, the playful heiress, the sensual companion – with unnerving ease. Yet, beneath the charm, there's a coldness, a predatory stillness that suggests the immense control required to live such a life. Is she purely evil, or is there a loneliness driving her? The film wisely leaves much of this ambiguous, allowing Russell's enigmatic performance to hold our gaze. It was crucial to find the right actress to embody this seductive cipher opposite Winger, and Russell feels like pitch-perfect casting.

Style and Substance

Director Bob Rafelson, a filmmaker perhaps best known for character studies like Five Easy Pieces (1970) and The King of Marvin Gardens (1972) – and somewhat amusingly, the co-creator of The Monkees TV show – brings a cool, observational detachment to the proceedings. This isn't a film filled with frantic set pieces. Instead, Rafelson focuses on mood, atmosphere, and the intricate psychological interplay. He's aided immensely by the legendary cinematographer Conrad L. Hall (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969)), whose work lends the film a sleek, polished look. The contrast between Alex's drab D.C. offices and Catherine's luxurious haunts – sun-drenched Hawaii (filmed partly at the Mauna Kea Beach Hotel), sophisticated Seattle, the elegance of Capri – visually underscores the chasm between their lives, and the allure of the world Alex finds herself drawn into. Michael Small's score complements this perfectly, adding layers of suspense without overwhelming the character drama.

Retro Fun Facts: Behind the Silk Web

- The screenplay by Ronald Bass, who would later win an Oscar for Rain Man (1988), reportedly languished in development for years before finally getting made. Its success helped solidify Bass as a go-to writer for smart, adult-oriented Hollywood fare.

- The film’s budget was around $10 million, and it grossed a respectable $24 million worldwide – a solid return for a character-focused thriller in an era increasingly dominated by high-octane action. Adjusted for inflation, that $24 million box office is closer to $65 million today.

- The evocative tagline used in some marketing, "She mates for life. Hers," perfectly captured the film's deadly premise and noirish wit.

- While Winger and Russell dominate, the supporting cast includes reliable faces like Dennis Hopper and Diane Ladd in brief but memorable roles, adding texture to the world Alex navigates. And Sami Frey as Paul, Catherine's final, perhaps more complicated target, brings a continental charm that makes Alex's protective instincts feel earned.

Lingering Questions

Does Black Widow fully satisfy as a thriller? Perhaps the plot mechanics become slightly less compelling once Alex closes in on Catherine in Hawaii. The real fascination isn't if Catherine will be caught, but what drives these two women. What does Alex truly want? Justice? Or does she envy Catherine's freedom, her audacity, her rejection of societal constraints? What does Catherine see in Alex – a worthy adversary, a kindred spirit trapped in a dull life, or simply the inevitable end to her game? The film poses these questions more effectively than it answers them, leaving a residue of ambiguity that lingers long after the credits roll.

I remember renting this one on VHS, drawn in by the promise of a sophisticated, female-driven mystery. It felt different from the usual fare, less about explosions and more about the quiet tension building between two complex characters. Watching it again now, it holds up remarkably well, primarily due to the strength of its lead performances and its confident, atmospheric direction. It’s a snapshot of a certain kind of glossy, intelligent 80s filmmaking that seemed aimed squarely at adults.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's success in creating a palpable atmosphere of suspense and psychological intrigue, anchored by two truly outstanding performances from Debra Winger and Theresa Russell. The stylish direction, sharp script (for the most part), and memorable locations make it a standout neo-noir thriller from the era. While the third act might not fully maintain the brilliance of the setup, the core relationship between hunter and hunted remains utterly compelling.

Black Widow endures not just as a clever thriller, but as a fascinating study of obsession and mirrored identities, leaving you to ponder the complex, often unseen connections that can form between even the most disparate lives. What darkness, or perhaps what freedom, did Alex ultimately find when she stared into the eyes of the spider?