Okay, pull up a metaphorical beanbag chair and let’s talk about a little piece of animation history that might have flickered across your CRT screen late one night, or maybe nestled amongst other curiosities on a compilation tape. It’s a short film, barely four minutes long, yet it resonates with a quiet melancholy and showcases a burgeoning digital artistry that hinted at wonders to come. I’m talking about Pixar’s 1987 creation, Red's Dream.

Rain lashes against the glass of a lonely bicycle shop window, blurring the neon glow from outside. Inside, tucked away in the "Clearance Corner" amongst forgotten parts and dusty price tags, sits Red – a bright red unicycle. This opening image, rendered with a complexity that was genuinely startling for computer animation at the time, immediately sets a mood. It's late, it's quiet, and there's a palpable sense of longing hanging in the air. We weren’t quite in the Toy Story era of fully realized digital worlds yet, but the seeds were undeniably being sown here.

### More Than Just Pixels

Directed and written by John Lasseter, who had already charmed audiences with the playful Luxo Jr. (1986), Red's Dream represented a significant leap forward for the fledgling Pixar animation team. While Luxo Jr. focused on character and movement, Red's Dream aimed for something more ambitious: atmosphere, emotion, and a far more complex visual environment. They wanted to tell a story purely through visuals and mood, exploring the inner life of an inanimate object – a theme that would become a Pixar hallmark.

The technical hurdles were immense. Creating the rain-streaked window, the reflections on the wet floor, and the deep shadows of the bike shop pushed the limits of their bespoke Pixar Image Computer. Render times were astronomical, demanding patience and ingenuity. Lasseter and his team, including key figures like Eben Ostby (whose name graces the bike shop sign, a fun Easter egg) and William Reeves (who tackled the complex water effects), were essentially inventing techniques as they went. This wasn't just filmmaking; it was pioneering digital exploration, crafting emotional resonance from lines of code. The specific software rendering the complex shapes and surfaces, nicknamed 'Chapreyes', was instrumental in bringing Red and his world to life with a solidity that felt revolutionary.

### A Unicycle's Reverie

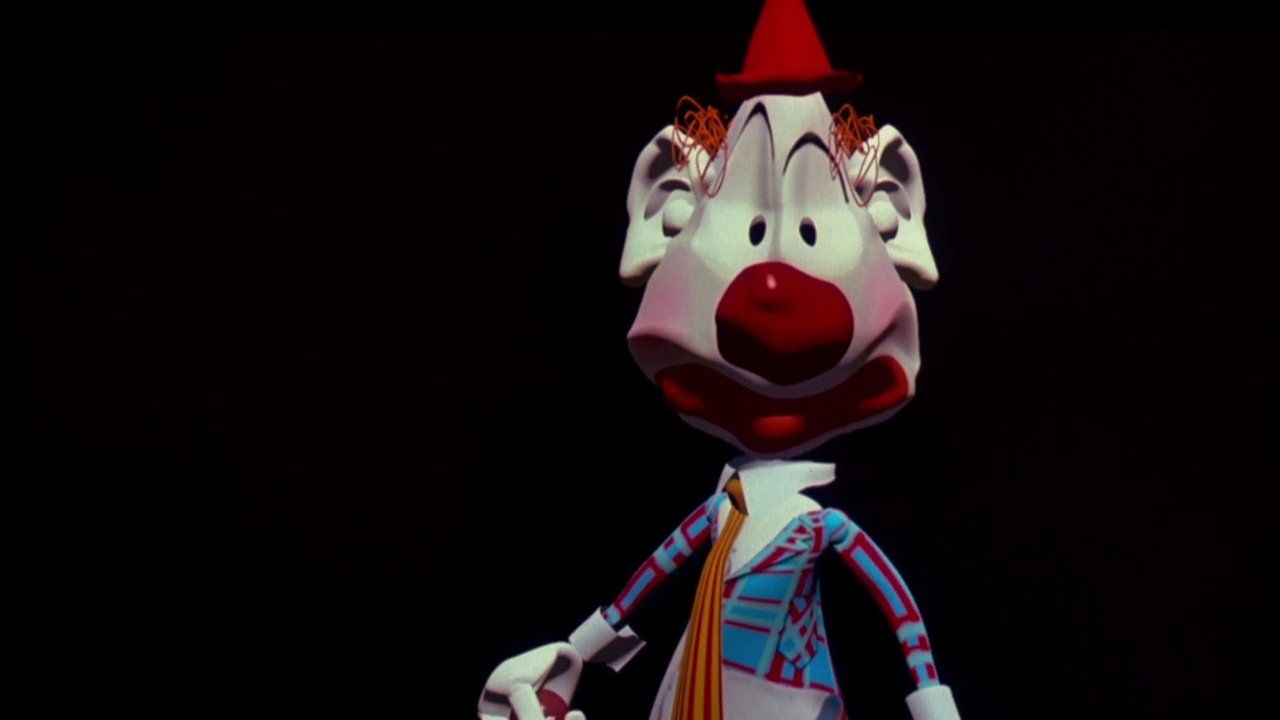

The core of the film lies in its title: Red’s dream. As the camera closes in, Red drifts off, and the drab reality of the shop dissolves into a vibrant, abstract circus stage. Suddenly, Red is the star, juggling brightly coloured balls under a spotlight, expertly maneuvered by a mostly unseen clown character (rendered intentionally simplistic, almost ethereal). It’s a moment of pure wish fulfillment, a brief escape from the dusty corner to a place of purpose and applause.

The animation in the dream sequence is fluid and expressive. Red bounces, balances, and interacts with the juggling balls with a personality all his own. You feel his temporary joy, the liberation from his static existence. But like many dreams, it's fleeting. The applause fades, the spotlight dims, and Red finds himself back in the silent shop, the rain still falling outside. The final shot, Red slumped slightly, seemingly dejected, is surprisingly poignant for a film about a unicycle. There's a genuine pathos there, a quiet understanding of dashed hopes and the longing for something more.

### A Glimpse of the Future

Red's Dream didn't achieve the instant iconic status of Luxo Jr. Its mood is perhaps too downbeat, its narrative too simple for widespread appeal at the time. Yet, its significance is undeniable. It demonstrated Pixar's growing ability to imbue digital characters with emotion and place them in richly detailed, atmospheric environments. The sophisticated lighting, the realistic textures (for 1987!), and the sheer ambition of the piece were signposts pointing directly towards the feature films that would eventually redefine animation. Watching it now feels like uncovering a vital piece of the puzzle, a crucial step on the journey to Andy's room and beyond. It didn't make millions (it wasn't intended to), but its value lay in pushing boundaries and proving capabilities, both internally at Pixar and to the wider industry.

This wasn't just a technical exercise; it was Lasseter and his team proving that computers could be used not just for flashy effects, but for genuine storytelling, capable of evoking feelings beyond simple amusement. The melancholy might seem unusual for what we now associate with Pixar, but it showcases their early willingness to explore different emotional registers.

***

VHS Heaven Rating: 7/10

Justification: Red's Dream earns a solid 7 primarily for its historical significance and technical ambition within the context of 1987 computer animation. It’s a beautifully moody piece that showcased Pixar's burgeoning talent for visual storytelling and emotional depth, particularly impressive given the technological limitations. The rain effects and lighting were groundbreaking. While its simple narrative and melancholic tone might not resonate as strongly as their later, more complex works, and its brevity limits its scope, it remains a crucial and poignant stepping stone in animation history. It successfully evokes empathy for an inanimate object, a remarkable feat.

Final Thought: A quiet, beautiful blue note in the Pixar symphony, Red's Dream reminds us that even in the earliest days of digital dreams, there was room for heartfelt melancholy and the quiet wish for a place in the spotlight. A must-see for animation history buffs and anyone curious about the dawn of CGI storytelling.