The spine cracks open, releasing the scent of old paper and dried ink. But sometimes, what spills out is far darker. Imagine the words refusing to stay put, the villain deciding the page is too small a prison. That’s the unsettling pact Tibor Takács’ I, Madman (1989) makes with its audience – a pact sealed not just with ink, but with something far more visceral. It suggests that the most terrifying monsters might not be lurking under the bed, but between the covers of that dog-eared paperback you can't put down.

Words Made Flesh

We follow Virginia (Jenny Wright, bringing that same haunted intensity she showcased in Near Dark), a secondhand bookstore employee in late-80s Los Angeles with a penchant for lurid pulp horror novels. She becomes utterly consumed by "I, Madman," a supposedly non-fiction account of the grotesque Dr. Alan Kessler, a mad surgeon obsessed with winning the love of an actress by… well, by surgically altering his own face using parts harvested from his victims, transforming himself into the monstrous Malcolm Brand. The prose is purple, the scenarios ghastly – perfect late-night reading material.

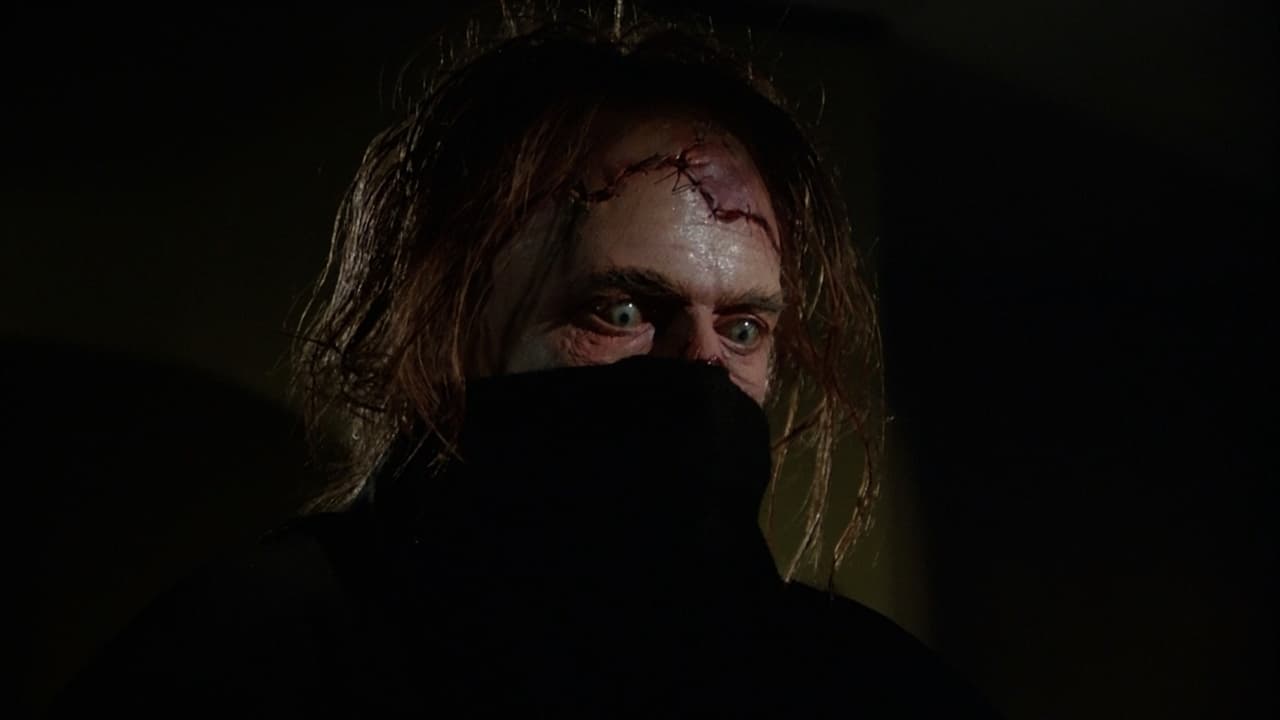

Except, the murders described in the book start happening in Virginia’s reality. And Malcolm Brand (Randall William Cook), with his crudely stitched, cadaverous visage, begins appearing to her, seemingly stepping directly from the novel's blood-soaked pages. Is Virginia losing her grip, projecting her literary obsession onto reality? Or has she truly unleashed a fictional nightmare upon the world? It’s a premise ripe with meta-textual dread, playing on the intimate, sometimes obsessive relationship readers form with fiction.

The Madman and His Maker

The film truly comes alive whenever Brand is on screen. Randall William Cook delivers a performance that’s both physically imposing and unnervingly restrained. His movements are deliberate, almost theatrical, fitting for a character born from prose. But the real kicker? Cook wasn't just the actor beneath the gruesome makeup; he was also a seasoned stop-motion animator and effects artist (who would later win Oscars for his work on The Lord of the Rings trilogy!). This unique dual role feels baked into the film's DNA. Cook reportedly relished playing the monster, directly informing the practical effects needed to bring Brand to life. You can almost feel his understanding of physical performance blending with his technical expertise.

Director Tibor Takács, fresh off the suburban demonic chaos of The Gate (1987), swaps miniature demons for a singular, literary boogeyman. He crafts a wonderfully gloomy atmosphere, contrasting the bright, almost sterile feel of Virginia's bookstore and apartment with the shadowy, fog-drenched appearances of Brand. The film often feels like a forgotten noir filtered through a pulp horror lens. There’s a tangible sense of unease, particularly in the sequences where reality seems to fray at the edges for Virginia. That nagging question – is he real? – is the engine driving the suspense.

Stop-Motion Nightmares and Pulp Charm

And then there’s that creature. Brand doesn't just rely on his scalpel; he unleashes a hideous, stop-motion demon resembling a skeletal jackal-muppet hybrid from hell. Pulled straight from the book’s climax, its jerky, unnatural movements possess a distinct kind of vintage creepiness. It’s pure Ray Harryhausen by way of 80s horror grit. Sure, by today’s standards it looks dated, but back on a flickering CRT screen rented from the local video store? That little beast felt like a tangible, skittering nightmare. It’s a testament to the power of practical effects, imbued with a personality that slick CGI often lacks. This sequence, coupled with Brand's own increasingly decayed appearance, represents the film's commitment to its pulpy, effects-driven horror roots.

While Jenny Wright carries the film admirably, portraying Virginia's mounting terror and crumbling sanity effectively, the supporting cast, including Clayton Rohner (April Fool's Day) as her skeptical detective boyfriend, fill their roles serviceably without stealing the spotlight. The focus remains squarely on Virginia's psychological battle and Brand's terrifying intrusions. It's worth noting the script comes from David Chaskin, who penned the fascinatingly subtext-laden A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy's Revenge. While I, Madman isn't as layered, the shared DNA of a monstrous figure crossing the threshold from an unreal space into the victim's world is certainly present.

A Cult Classic Between the Covers

I, Madman wasn't a box office smash – pulling in a mere $162,714, it quickly faded into the VHS racks, destined for cult status. It arrived perhaps a touch too late, at the tail end of the 80s slasher boom and just before the horror landscape shifted again. Yet, it remains a fascinating artifact. Its blend of psychological horror, creature feature, and meta-narrative feels distinctive. The central conceit is strong, Randall William Cook's dual contribution is remarkable, and the atmosphere genuinely unsettling at times. It captures that specific late-80s horror vibe – dark, a little grimy, reliant on practical gore and creature work, and possessing a sincerity often missing in slicker productions. Does the logic hold up under intense scrutiny? Perhaps not entirely. But does it deliver a unique and memorable slice of VHS-era dread? Absolutely.

VHS Heaven Rating: 7/10

Justification: I, Madman earns its score through its strong central concept, genuinely creepy villain design and performance (elevated by Cook's dual role), effective atmospheric direction by Takács, and memorable practical effects, particularly the stop-motion creature. It successfully evokes that late-night, page-turning dread. Points are slightly deducted for occasionally uneven pacing and supporting characters who don't quite match the intensity of the leads or the core premise. However, its unique blend of elements makes it a standout piece of late-80s horror.

Final Thought: I, Madman remains a potent reminder from the VHS era that sometimes, the stories we consume can consume us right back, leaving behind more than just papercuts.