The faint hum of the VCR, the static bloom on the CRT screen… sometimes revisiting a sequel feels like trying to recapture a specific, fading echo. Three years after Tibor Takács unleashed pint-sized chaos in The Gate (1987), he coaxed us back to that hole in the ground with Gate II (released in some markets as Gate II: Trespassers, 1990). But the dark energy felt… different this time. Less pure, cosmic dread, more grubby, transactional horror born from teenage desires twisted into grotesque reality. It wasn't just about stopping demons; it was about the terrifying consequences of getting exactly what you wished for.

Return to the Abyss

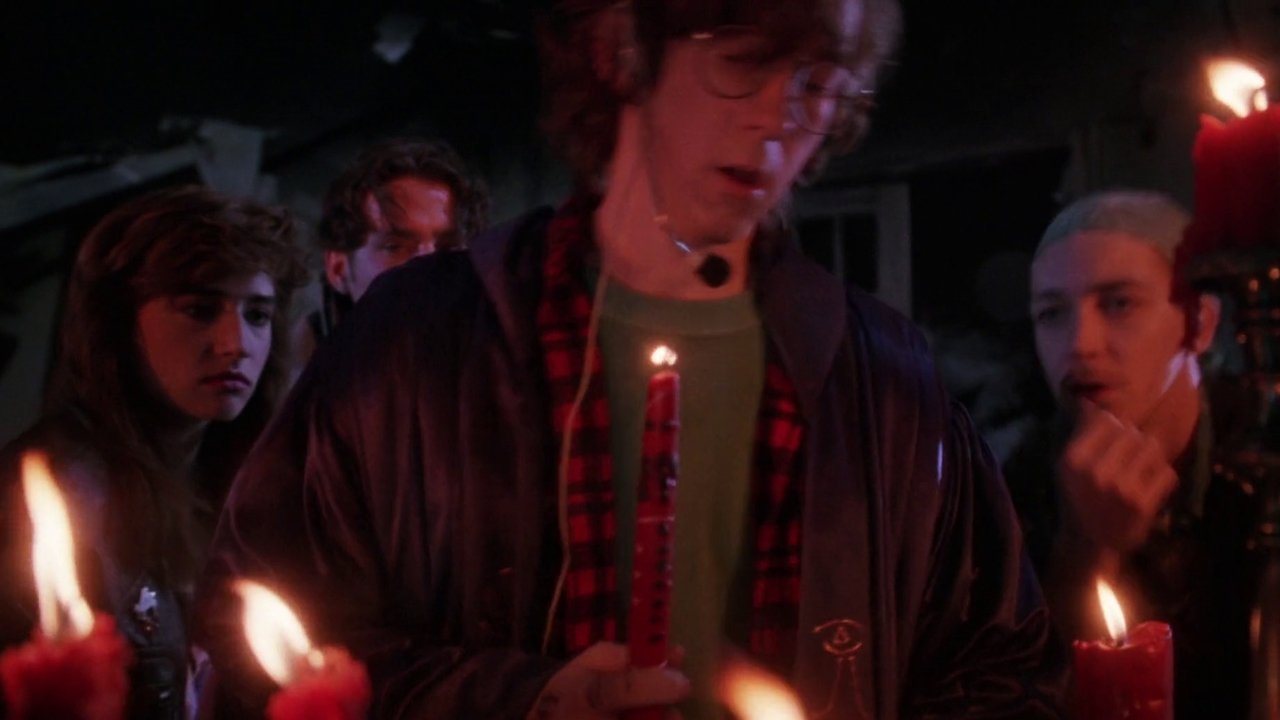

We find Louis Tripp reprising his role as Terry, the metal-loving kid who survived the first film's demonic onslaught. He's older now, still fascinated by the occult energies simmering beneath his suburban normality. The original house is empty, a silent monument to past terror, but Terry can't resist one last ritual, hoping perhaps to harness the gate's power rather than merely survive it. He's joined by two skeptical friends, the ambitious John (Simon Reynolds) and the pragmatic Liz (Pamela Adlon – yes, that Pamela Adlon, years before King of the Hill or Better Things!), who stumble into his dangerous hobby. This time, the invocation isn't just about opening a door; it’s about making deals, pulling forth something malleable, something that grants wishes… at a terrible price.

Minions Before Minions Were Cool (and Yellow)

Forget the towering demons and swarms of tiny terrors from the first film. Gate II's primary threat comes in the form of the 'Minions' – small, fleshy, vaguely humanoid creatures birthed from wishes. Think Play-Doh figures sculpted by H.R. Giger after a bad trip. While the ambition of the practical effects is commendable, especially on what was reportedly a tighter budget than its predecessor, they lack the visceral nightmare fuel of the original's creatures. There's a certain B-movie charm to their jerky movements and uncanny valley faces, achieved primarily through puppetry and some forced perspective shots, but they often feel more peculiar than petrifying. Did the design still manage to unnerve you back then, or did it feel like a step down even on a fuzzy VHS copy?

One infamous sequence involves a dog transforming, a moment of body horror that aimed for Cronenbergian shock but perhaps landed closer to rubbery weirdness. It’s a classic example of the kind of practical effect that felt wildly ambitious in the video store aisle, even if it doesn’t quite hold up under scrutiny today. Takács, returning to direct, seemed intent on exploring the creative potential of the gate's dark magic, rather than just its destructive force. It's an interesting idea, but the execution sometimes struggles to match the concept's inherent creepiness.

Wish Fulfillment Nightmares

Where The Gate excelled in claustrophobic siege horror, Gate II shifts its focus to the moral decay of its characters. John, in particular, sees the Minions as a shortcut to wealth and power, his wishes escalating from conjuring cash to far more sinister manipulations. Simon Reynolds plays this descent convincingly, capturing the seductive allure of power without consequence. Terry, meanwhile, seems more conflicted, caught between his fascination and the growing realization that this magic is inherently corrupting. Louis Tripp, who apparently needed some convincing to return to the role that defined his early career, brings a weary maturity to Terry, a kid who’s seen too much darkness already.

The atmosphere here is less outright terrifying and more subtly unsettling. The dread comes not from jump scares, but from watching characters willingly invite darkness into their lives, bartering pieces of themselves for fleeting gains. The film hints at a larger, darker universe connected to the gate, but keeps the focus tight on the trio and their wish-granting abominations. The score and sound design work to maintain a low hum of anxiety, even if the film lacks the relentless tension of the original. It feels like a story told under flickering fluorescent lights in a damp basement, rather than the primal darkness of the first film’s storm-lashed night.

Echoes in the Static

Gate II didn't make much noise at the box office, quickly finding its home on video store shelves where it likely confused or mildly disappointed fans expecting a straight repeat of the original's formula. It grossed a mere $2 million against its (admittedly lower) budget, fading faster than a poorly tracked tape. Yet, there's a strange persistence to it. It represents that common VHS-era phenomenon: the sequel that takes a weird left turn, trying something different but ultimately failing to recapture the lightning in a bottle.

There are stories of script changes focusing even more heavily on the relationship drama, and while Takács clearly had ideas he wanted to explore, the final product feels somewhat compromised, caught between being a creature feature and a darker character study. Does it work? Not entirely. Is it fascinating? In its own way, yes. It’s a curious artifact, a testament to a time when even lower-budget horror sequels could swing for the fences with bizarre concepts and gooey practical effects. I distinctly remember renting this one hoping for more of the same chaotic energy as the first, and feeling… well, different afterward. Not scared in the same way, but certainly pondering the ugliness of unchecked desire.

VHS Heaven Rating: 4/10

Let's be honest, Gate II is a significant step down from its predecessor. The shift in focus from pure horror to wish-fulfillment drama, coupled with less impressive creature effects and a palpable feeling of diminished resources, prevents it from reaching the cult classic status of the original. The performances are decent, and the core concept holds a certain dark allure, but the execution is uneven, often feeling more like a strange TV movie than a theatrical horror sequel. The 4 is earned by its ambition (however flawed), some memorably weird practical effects moments, and Louis Tripp’s committed return. It tried something different, which is commendable, but ultimately fumbled the dark magic.

Still, for the dedicated VHS archeologist, Gate II remains a fascinating specimen – a sequel that dared to deviate, offering a glimpse into a weirder, perhaps more mundane, kind of suburban hell. It’s less a terrifying portal to another dimension, and more a grimy mirror reflecting the darkness already lurking within.