There's a certain kind of quiet shock that settles in when an icon decides to dismantle their own image right before your eyes. Pulling the White Hunter, Black Heart (1990) tape from its clamshell case back in the day often came with a specific expectation: another stoic, Eastwoodian adventure. What spooled out on the CRT, however, was something far more unsettling and fascinating – a portrait not of heroism, but of profound, consuming obsession. It wasn't the film many expected from Clint Eastwood, then still firmly rooted in the public consciousness as Dirty Harry or the Man With No Name, and perhaps that's precisely why it lingers.

A Different Kind of Safari

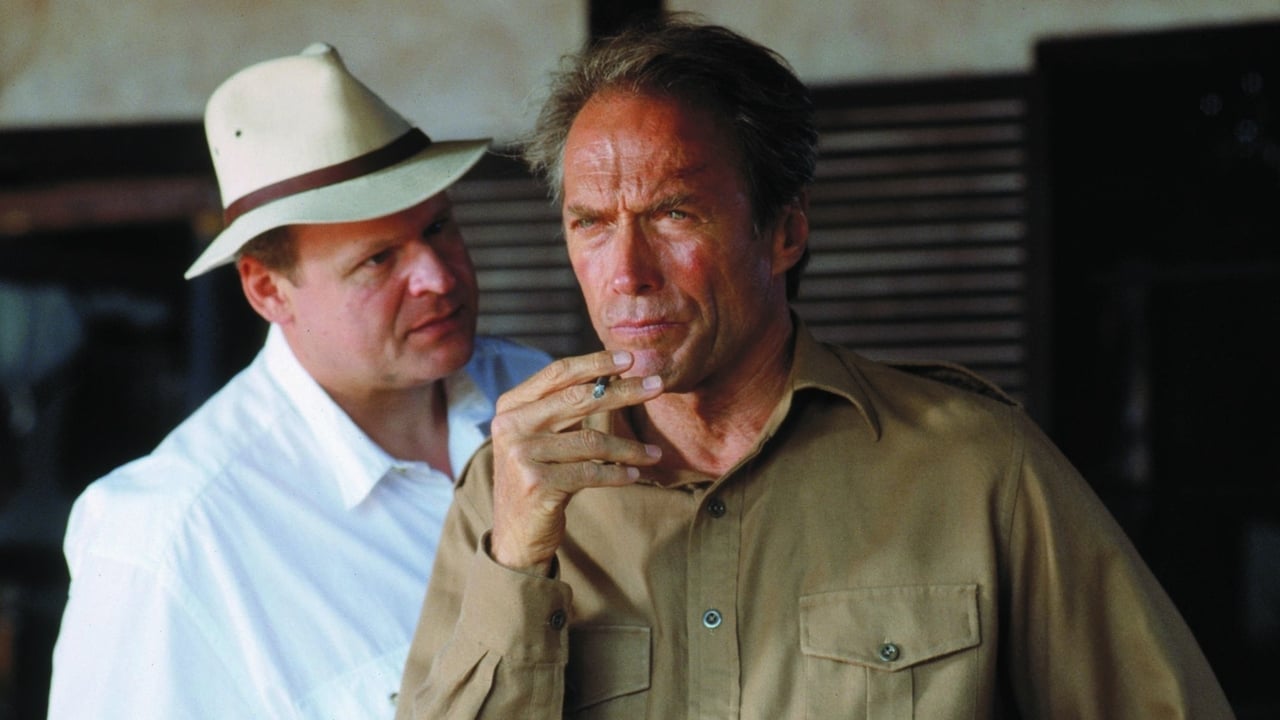

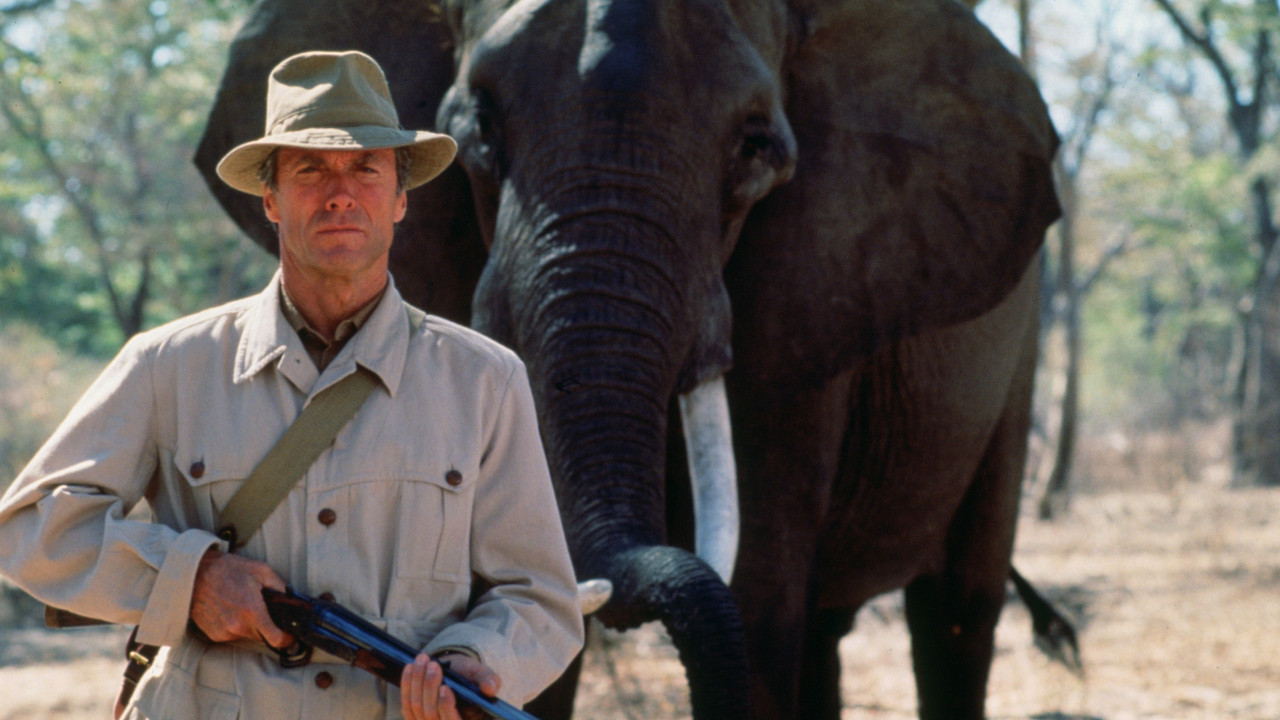

Based on Peter Viertel's thinly veiled roman à clef about the chaotic pre-production of The African Queen (1951), the film follows legendary (and legendarily difficult) director John Wilson (Clint Eastwood) as he heads to Africa, ostensibly to scout locations for his next big picture. Accompanying him is young writer Pete Verrill (Jeff Fahey, bringing a necessary grounding presence), who serves as both collaborator and increasingly concerned observer. Wilson, a thinly disguised John Huston, is charming, brilliant, infuriatingly charismatic, and dangerously fixated. His true quarry isn't cinematic gold, but the thrill of hunting a magnificent bull elephant, an obsession that threatens to derail the entire production and endanger everyone involved.

It’s a narrative that immediately sets itself apart. This isn't about taming the wilderness; it's about confronting the wilderness within a man. What drives someone to place a personal, primal urge above their art, their responsibilities, even the safety of their colleagues? The film doesn't offer easy answers, instead immersing us in Wilson's magnetic yet repellent orbit.

Eastwood Unbound

The absolute core of White Hunter, Black Heart is Eastwood's audacious performance. Shedding his familiar taciturn squint and gravelly murmur, he adopts the flamboyant mannerisms, the clipped, almost theatrical speech patterns, and the devil-may-care attitude of John Huston. I remember watching it for the first time, the sheer difference in his portrayal being almost jarring. It wasn't just an imitation; it felt like an inhabitation. Eastwood captures the intoxicating blend of genius and monstrous ego that defined Huston – a man who could charm birds from the trees one moment and casually risk lives the next. There’s a scene where Wilson callously provokes a confrontation over anti-Semitic remarks that is genuinely uncomfortable, showcasing the character's moral failings without flinching. It’s a performance that feels deeply considered, a deliberate effort by Eastwood, the director, to push Eastwood, the actor, into uncomfortable, revealing territory. Does his distinctive physicality sometimes peek through the Huston facade? Perhaps, but the commitment to the portrayal is undeniable and deeply compelling. It’s the kind of acting choice that felt risky then and remains fascinating now.

The Price of Obsession

Supporting Eastwood, Jeff Fahey does commendable work as Verrill, our surrogate. His growing disillusionment and quiet horror mirror our own as Wilson's quest escalates. George Dzundza also provides sturdy support as the pragmatic producer, Paul Landers, trying desperately to keep the runaway train of Wilson's ego on the tracks. But ultimately, this is Wilson's show, and the film orbits his increasingly erratic behaviour.

Director Eastwood uses the stunning Zimbabwean locations (standing in for 1950s Central Africa) not just as backdrop, but as a participant in the drama. The vast landscapes seem to amplify Wilson's internal turmoil, reflecting both the allure and the danger of his obsession. There's a raw, unvarnished quality to the filmmaking, fitting for a story about stripping away pretence.

Retro Fun Facts & Lingering Questions

It’s worth remembering that White Hunter, Black Heart was a passion project for Eastwood, one he’d wanted to make for years. He felt a kinship with Huston's maverick spirit, even while the film critiques his excesses. Author Peter Viertel was directly involved, co-writing the screenplay based on his own novel and experiences, lending an air of authenticity. The budget was around $24 million, but it only grossed a fraction of that ($2.3 million domestically), making it a commercial disappointment. Perhaps audiences in 1990 simply weren't ready for this kind of complex, deconstructive role from their action hero. Interestingly, the film carries a subtle but definite anti-hunting message, a layer of irony given the title and the protagonist's drive. It’s less about the thrill of the hunt and more about the hollowness of the need to dominate. What does it say about masculinity, particularly the kind often celebrated in cinema, when its ultimate expression becomes so destructive? Doesn't that question still echo today?

The film wasn't a box office smash, nor did it redefine Eastwood's career overnight – that would arguably come two years later with the masterful Unforgiven (1992). Yet, White Hunter, Black Heart occupies a unique and vital space in his filmography. It’s a bold swing, a challenging character study disguised as an adventure film. It asks uncomfortable questions about the nature of artistic drive, ego, and the darkness that can lie beneath a charismatic surface.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's ambition, Eastwood's daring and largely successful central performance, and its willingness to explore complex, uncomfortable themes. It's not a perfect film – the pacing occasionally lags, and Wilson's relentless self-absorption can be wearying – but its strengths far outweigh its flaws. It avoids easy moralizing, presenting a flawed man in full, forcing us to grapple with his contradictions.

White Hunter, Black Heart might not have been the Eastwood film audiences clamoured for on its release, but revisiting it now, it feels like a vital, even necessary, exploration of the very archetypes Eastwood himself often embodied. It's a reminder that sometimes the most dangerous beasts aren't found in the jungle, but within the human heart itself.