There’s a certain kind of quiet that settles over you after watching Jim Jarmusch's Dead Man. It’s not the silence of an empty room, but the echoing resonance of a struck chord – low, electric, and lingering. Released in 1995, amidst a decade often defined by explosive action and quippy comedies, this film arrived like a ghost transmission from another frequency entirely. It wasn't shouting for attention; it was whispering profound, unsettling truths about life, death, and the brutal poetry of the American frontier, all filtered through Jarmusch's uniquely laconic, darkly humorous lens.

Into the Black and White West

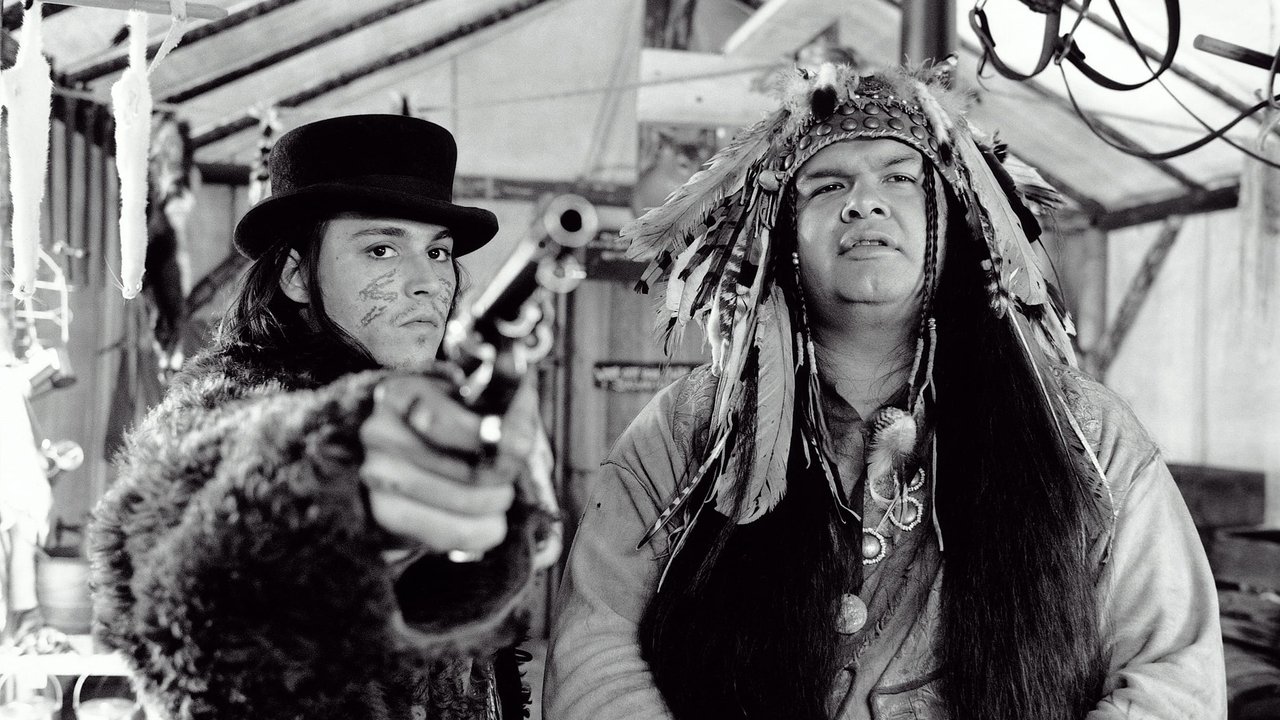

The film opens with a journey, a recurring motif in Jarmusch’s work, like Down by Law (1986) or Mystery Train (1989). We meet William Blake (Johnny Depp), a mild-mannered accountant from Cleveland, traveling west by train to the godforsaken company town of Machine. The sequence itself is hypnotic, punctuated by the stark, almost industrial warnings of a soot-covered train fireman (Crispin Glover in a typically unsettling cameo) about the hellish destination. This isn't the romanticized West of John Ford; it’s a grimy, indifferent landscape rendered in glorious, high-contrast black and white by the legendary cinematographer Robby Müller, who had previously lensed existential journeys like Paris, Texas (1984). Müller’s work here isn't just beautiful; it’s essential, stripping the world down to stark textures of wood grain, smoke, mud, and later, vast, empty wilderness. It feels less like a period piece and more like an unearthed daguerreotype pulsing with strange life.

A Poet Misunderstood

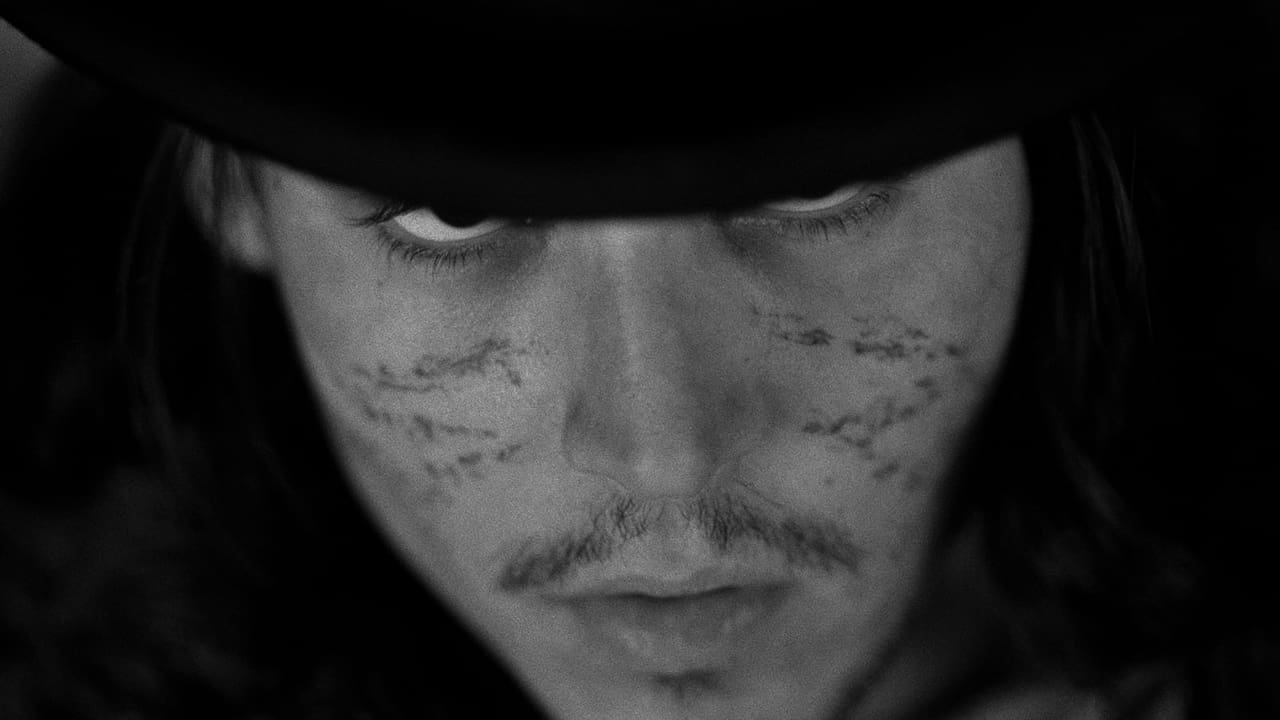

Blake’s arrival in Machine is swift and disastrous. A misunderstanding involving a former lover (Mili Avital) and her enraged ex (Gabriel Byrne) leaves Blake grievously wounded and branded a killer, with a bullet lodged near his heart. Fleeing into the wilderness, he encounters a large, philosophical Native American named Nobody (Gary Farmer). Nobody, exiled from his own people for having been educated by whites and then returned, mistakes the accountant for the English visionary poet William Blake. This case of mistaken identity becomes the film’s spiritual engine. Farmer’s performance is magnificent – commanding, wry, deeply soulful. He sees not a dying accountant, but the resurrected spirit of a poet destined for the spirit world, and resolves to guide him there. Depp, known then for more overtly expressive roles, delivers a masterclass in quiet transformation. His Blake starts as a bewildered innocent, gradually shedding his identity, his fear, and eventually, his very sense of self as the journey progresses and the inevitability of death looms. There’s a profound truthfulness in his portrayal of fading awareness mixed with moments of startling clarity or violence.

Encounters on the Edge of Oblivion

The journey itself is less a plot-driven narrative and more a series of hallucinatory encounters. Blake and Nobody drift through forests and ramshackle settlements, pursued by three distinctively absurd bounty hunters (a verbose Lance Henriksen, a cannibalistic Michael Wincott, and a perpetually napping Eugene Byrd). Along the way, they cross paths with other indelible characters: grubby, bible-quoting frontiersmen played by Iggy Pop and Billy Bob Thornton, and, in a truly poignant moment, the industrialist Dickinson, the very man Blake came west to work for, played by screen legend Robert Mitchum in his final film role. Mitchum’s brief scene, filled with weary menace, serves as a powerful link to the classic Hollywood Westerns Jarmusch is simultaneously honoring and dismantling. These encounters feel less like plot points and more like fragmented verses in the film's strange, epic poem.

The Sound of the Soul's Decay

You simply cannot talk about Dead Man without discussing Neil Young's score. It's not background music; it's the film's pulse, its nervous system. Jarmusch reportedly showed Young a rough cut and asked him to improvise. Armed with his electric guitar, "Old Black," an acoustic guitar, piano, and organ, Young watched the film multiple times, essentially playing to it. The result is astonishing – raw, feedback-drenched chords, lonely acoustic melodies, and dissonant bursts that perfectly mirror Blake's physical and spiritual dissolution. The score feels organic, unpredictable, emerging directly from the stark visuals and existential dread. It’s one of the most unique and effective film scores of the 90s, perhaps ever, existing entirely outside conventional scoring techniques. It’s a sound I distinctly remember feeling deep in my bones when I first rented this on VHS, likely tucked away in the "Independent" section, a world away from the multiplex hits.

A Different Kind of Journey

Dead Man wasn't a box office sensation ($1 million gross on an estimated $9 million budget). Its deliberate pacing, philosophical musings, and rejection of genre conventions polarized critics and audiences initially. Yet, like many films discovered on those humming shelves of the video store, its reputation grew steadily, cementing its status as a definitive cult classic, often labelled an "acid Western" or "psychedelic Western." It feels utterly singular. Jarmusch uses the Western framework not for heroics, but to explore themes of cultural collision, violence, the power of naming, and the journey towards death as a passage, not an endpoint. Nobody's line, "That weapon will replace your tongue... You will learn to speak through it. And your poetry will now be written with blood," resonates long after the credits roll.

Does the film ask more questions than it answers? Absolutely. What does it truly mean to be "dead"? Is Blake's journey literal, metaphorical, or both? These ambiguities are not flaws; they are the source of the film's enduring power.

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's masterful artistry, its unforgettable atmosphere, the haunting power of its performances (especially Farmer and Depp), and its audacious, singular vision. The cinematography and score alone are worth the price of admission (or rental!). It might not be for everyone – its pace is meditative, its humor dark, its meaning elusive – but for those willing to take the journey, Dead Man offers a cinematic experience unlike any other from the era. It’s a film that truly gets under your skin and stays there, a haunting poem written in monochrome and electric guitar feedback. It leaves you contemplating the thin veil between worlds, long after the tape has clicked off.