It arrives not like a film, but like a flood. Wave upon wave of image, text, and sound wash over the viewer, demanding surrender rather than simple observation. Peter Greenaway’s Prospero's Books (1991) isn't the sort of tape you'd casually grab for a Friday night pizza party; finding it nestled on the shelves of the local video store, perhaps in a slightly intimidating "Art House" section, felt like uncovering a forbidden text itself. This wasn't just Shakespeare's The Tempest; it was Shakespeare filtered through a radically inventive, sometimes overwhelming, visual imagination.

A Canvas, Not Just a Screen

To engage with Prospero's Books is to understand that Peter Greenaway, who also directed the similarly challenging The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (1989), approaches filmmaking not primarily as narrative storytelling, but as painting with light and motion. His background as a visual artist permeates every frame. The screen becomes a dense collage, often layering multiple images simultaneously – actors moving through baroque settings, anatomical drawings overlaid, calligraphic text scrolling across the action. It's a technique that owes much to early experiments with high-definition video technology (HDVS) and the Quantel Paintbox, a digital graphics workstation that was cutting-edge stuff back in the early 90s. Seeing this intricate layering compressed onto a VHS tape was an experience in itself – perhaps losing some razor clarity, but gaining a strange, almost softened, dreamlike quality. Did the inherent fuzziness of tape make Greenaway's dense compositions more palatable, or simply more mysterious?

Gielgud's Swan Song to the Bard

At the heart of this visual tempest stands Sir John Gielgud as Prospero. And not just as Prospero. In a move both audacious and inspired, Gielgud voices nearly every single character in the play. His iconic, mellifluous tones become the film's primary unifying force, weaving through the visual complexity. This wasn't just stunt casting; it was a profound statement. Gielgud had a lifelong relationship with The Tempest, first playing Prospero on stage in 1930 and revisiting the role multiple times over sixty years. Here, at 87, he embodies the exiled Duke not just physically, but vocally inhabits the entire world Shakespeare created. There's a fascinating behind-the-scenes detail: Gielgud reportedly recorded the entire voice track before principal photography began. The other actors, including Michael Clark as a wiry, punk-inflected Caliban and Isabelle Pasco as an ethereal Miranda, performed their physical roles reacting to his pre-recorded delivery, adding another layer of artifice and interpretation. It lends the film an extraordinary, almost godlike perspective, as if we are hearing the entire play recited from Prospero's own memory and imagination.

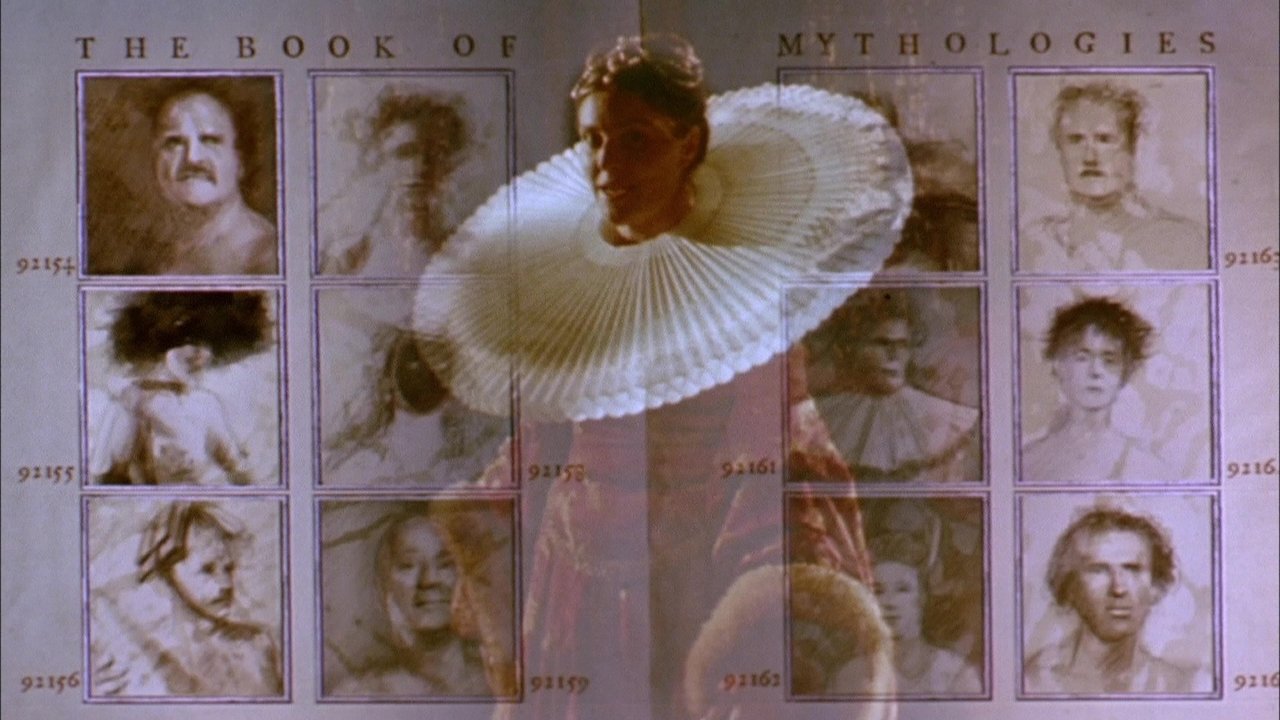

The Books Themselves

Central to Greenaway's concept are the 24 magical books Prospero salvaged from his library before his exile. Unlike Shakespeare's play, which merely alludes to them, the film visually catalogues each one. We get segments dedicated to A Book of Water, A Book of Mirrors, An Atlas of the Universal, The Book of Utopias, and so on. Each becomes an excuse for Greenaway to indulge his thematic and visual obsessions – mythology, anatomy, cartography, architecture, and the sheer power of knowledge and creation. These sequences are often stunning, filled with elaborate costumes, symbolic props, and a frankly staggering amount of choreographed nudity representing elemental spirits and mythological figures. It's a far cry from the Globe Theatre, and certainly pushed the boundaries of what audiences expected, even on the art house circuit. Gielgud himself, initially hesitant about the pervasive nudity, was apparently convinced by Greenaway that it was essential to capturing the primal, magical nature of the island.

Challenging the Narrative

Does it work? That's the question that likely echoed in dimly lit living rooms as the VHS tape whirred. For some, Greenaway's relentless visual invention is exhilarating, a bold attempt to translate the poetic richness of Shakespeare into a truly cinematic language. The sheer density of information – visual, textual, auditory – can be intoxicating. For others, it's undoubtedly overwhelming, even alienating. The narrative thrust of The Tempest, the clear lines of character and plot, often feel submerged beneath the stylistic deluge. Is it pretentious? Perhaps. Is it unforgettable? Absolutely. Finding this tape felt like a secret handshake amongst film buffs – a sign you were willing to venture beyond the mainstream, even if you weren't entirely sure what you'd just witnessed. It wasn't made for easy consumption; it demanded active participation, contemplation.

An Artifact of Ambition

Prospero's Books stands as a unique artifact from the cusp of the digital filmmaking revolution, using nascent technology to create something deeply personal and uncompromisingly artistic. It's a film about the power of language and image, embodied by Gielgud's monumental performance and Greenaway's radical vision. It asks us to consider how we interpret and re-imagine classic texts, and whether fidelity lies in literal adaptation or in capturing an essential spirit through entirely new means.

Rating: 8/10

The score reflects the film's undeniable artistic ambition, its groundbreaking visual techniques (for the time), and the towering, definitive performance by John Gielgud. It's a demanding, sometimes frustrating watch, and its narrative coherence occasionally drowns in the visual flood. However, its sheer uniqueness and audacious reimagining of a classic text make it a significant, if challenging, piece of cinema history. It's not a film you simply watch; it's one you experience, wrestle with, and ultimately, respect for its sheer, unwavering commitment to its singular vision.

It leaves you pondering not just Shakespeare's magic, but the potent, sometimes bewildering, magic of cinema itself when pushed to its limits. What other film feels quite like this one?