It arrives not with a bang, but with a cough. A creeping, inexplicable malaise that settles over Carol White like the pervasive smog of the San Fernando Valley she inhabits. Todd Haynes' 1995 masterpiece, Safe, isn't your typical slice of 90s cinema. Forget the grunge anthems or witty postmodern irony; this film offers something far more chilling, a quiet horror story unfolding under the bland California sun. Seeing its minimalist VHS box on the rental shelf back in the day, perhaps tucked between louder, more explosive fare, felt like finding a cryptic message. It promised something different, and boy, did it deliver – an experience that burrows under your skin and stays there long after the credits roll and the tape rewinds.

An Invisible Threat in a Sterile World

The film introduces us to Carol (Julianne Moore in a performance that remains utterly staggering), a woman adrift in the affluent emptiness of 1987 suburbia. Her life is a curated landscape of pastel tracksuits, impersonal modernist furniture, and polite, surface-level interactions with her husband Greg (Xander Berkeley). Haynes masterfully uses detached, often wide shots to emphasize Carol's isolation within these meticulously designed spaces. The camera observes her, almost clinically, as she navigates a world that feels both luxurious and suffocatingly sterile. There's a profound emptiness even before the illness takes hold, a sense that Carol is already allergic to her own life.

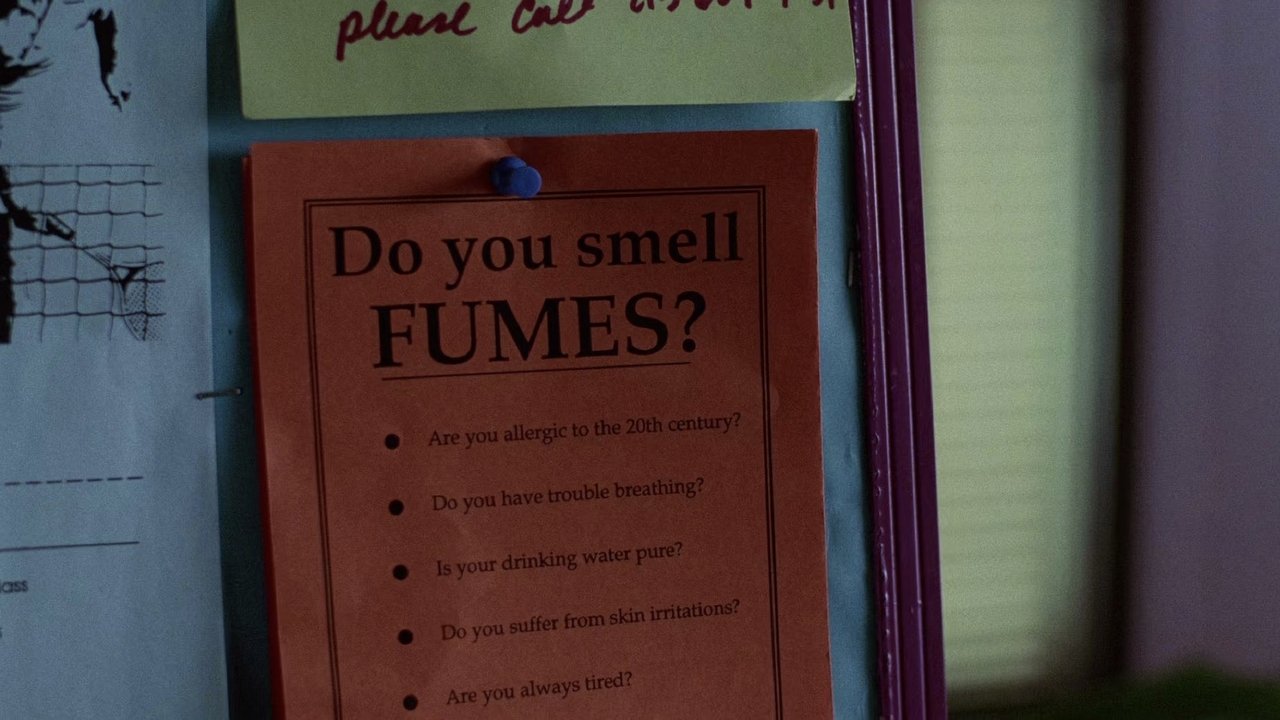

Then, the symptoms begin: nosebleeds, coughing fits, difficulty breathing, seizures. Doctors are baffled, offering vague diagnoses and platitudes. Is it stress? Is it psychosomatic? Or is it, as Carol comes to suspect, the environment itself – the fumes, the chemicals, the very fabric of modern existence – that is poisoning her? Haynes deliberately refrains from giving easy answers, plunging the viewer into the same uncertainty and mounting panic that grips Carol. The film becomes a slow-burn descent into a specific kind of existential dread, amplified by Ed Tomney's unnervingly sparse and discordant score.

The Disappearing Woman

What makes Safe so profoundly unsettling is Julianne Moore's central performance. This wasn't the fiery, Oscar-nominated star we know today; this was Moore announcing herself as a fearless, transformative talent. She doesn't just play Carol; she becomes her, physically diminishing as the illness progresses. Moore reportedly lost a significant amount of weight for the role, contributing to Carol's haunting fragility. Her voice becomes breathy, her movements tentative. She conveys oceans of fear, confusion, and a desperate yearning for relief with the barest of expressions. It's a portrayal devoid of melodrama, relying instead on unnerving subtlety. We watch a woman slowly fade, becoming almost translucent against the backdrop of her uncomprehending world. It's a performance that doesn't just ask for empathy; it quietly commands it through its raw vulnerability.

Interestingly, Haynes, who had previously directed the controversial Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story using Barbie dolls, drew inspiration for Safe from real-life accounts of what was then sometimes termed "20th-century disease" or environmental illness (now often discussed under Multiple Chemical Sensitivity). He wasn't necessarily making a direct statement about the illness itself, but using it as a potent metaphor for a deeper societal sickness – alienation, the hollowness of consumer culture, and the desperate search for meaning in a world that often feels toxic. The film's modest $1 million budget, far from being a limitation, arguably enhances its power, contributing to the stark, unsettling aesthetic.

Seeking Sanctuary, Finding...?

Carol's search for answers eventually leads her to Wrenwood, a desert retreat run by the charismatic but subtly manipulative Peter Dunning (Peter Friedman). It’s a community for people suffering from similar environmental sensitivities, promoting a philosophy of self-healing and positive thinking. Yet, Haynes films Wrenwood with the same ambiguous detachment he applied to Carol's suburban life. Is it a sanctuary, a place of genuine healing? Or is it merely another kind of sterile bubble, a cult-like environment demanding conformity and blaming the victim for their own suffering? The final scenes, particularly Carol's devastating self-affirmation in a mirror within her isolated porcelain igloo, offer no easy comfort. What does it mean to be "safe" if safety requires total isolation and self-negation?

The Lingering Chill

Safe wasn't a box office hit upon release. Its challenging themes and ambiguous narrative likely baffled mainstream audiences expecting clear resolutions. Yet, like so many significant films discovered on home video, its reputation grew steadily over the years. Critics revisited it, recognizing its artistry and prophetic insights. Now, it's widely regarded as one of the defining independent films of the 1990s, a chilling precursor to contemporary anxieties about wellness culture, environmental toxins, and the psychological toll of modern life. Haynes crafted a film that resists easy categorization – is it a horror film? A medical mystery? A social critique? It's all of those and none of them, existing in its own unique, unsettling space.

It’s a film that doesn’t provide answers but leaves you grappling with profound questions. What truly makes us sick? How much control do we have over our bodies and our environment? And in searching for safety and community, what might we inadvertently lose?

Rating: 9/10

Safe earns this high rating for its masterful direction, Julianne Moore's career-defining performance, its haunting atmosphere, and its enduring thematic resonance. It's a challenging, deeply unsettling film that uses its specific premise to explore universal anxieties with chilling precision. It might not have been the feel-good rental of the week back in '95, but its quiet power is undeniable and its questions linger, potent and unresolved, decades later. It remains a stark reminder that sometimes the most terrifying threats are the ones we can't easily see or name.