Okay, pull up a chair, maybe pour yourself something strong. We’re digging into a tape that doesn’t offer easy comfort or escapism, one that likely sat on the higher shelves of the 'World Cinema' section, radiating a quiet intensity. We’re talking about Michael Haneke’s 1992 film, Benny’s Video, a piece of Austrian cinema that burrows under your skin and stays there long after the VCR clicks off. This isn’t your typical Friday night rental fodder; it’s something far more chilling, a stark examination of a world becoming dangerously mediated.

The Unblinking Eye

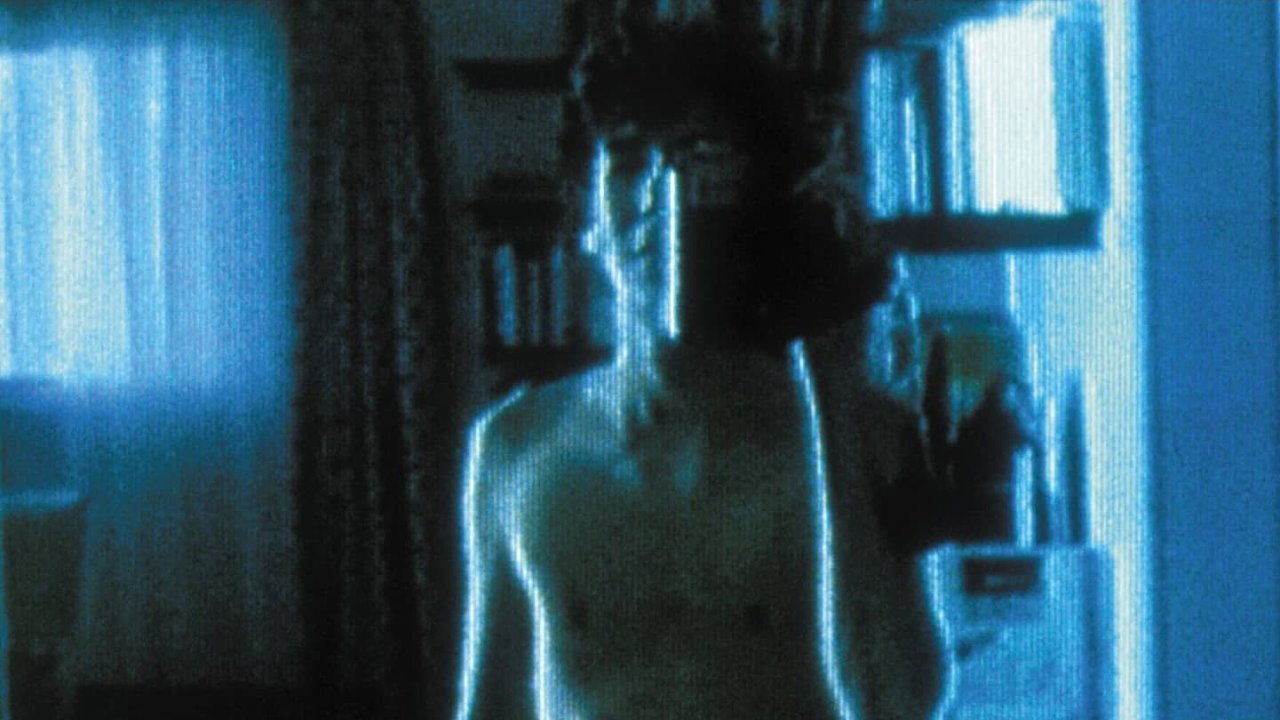

What strikes you first, and perhaps most unsettlingly, about Benny’s Video is its cold, almost clinical gaze. Haneke, who would later solidify his reputation for uncomfortable truths with films like Funny Games (1997) and The White Ribbon (2009), employs a deliberately detached style here. Long takes, often from a fixed perspective, mimic the impassive lens of the video camera Benny himself is obsessed with. We aren't guided emotionally; we are simply observers, forced to watch events unfold with a distance that mirrors the protagonist's own alarming lack of affect. The film opens not with a dramatic flourish, but with grainy home-video footage of a pig being dispatched with a captive bolt pistol – a recording Benny replays, rewinds, analyzes. It’s a brutal, unvarnished image, setting the stage for a narrative concerned with the normalization of violence through detached observation.

A Void Named Benny

At the heart of this cold landscape is Benny, portrayed with unnerving emptiness by Arno Frisch (who would later reunite with Haneke for the equally disturbing Funny Games). Benny is a teenager adrift in a comfortable, middle-class Viennese apartment, his primary relationship seemingly not with his often-absent parents, but with his video equipment. He lives vicariously through the screen, recording the world outside his window, consuming violent movies, and re-watching that unsettling pig footage. Frisch embodies this alienation perfectly; his Benny isn't overtly monstrous, but rather chillingly blank. There's a void where empathy or connection should be. When he commits a truly shocking act of violence – filmed, naturally – it’s presented with the same dispassion as everything else, an event seemingly devoid of emotional weight for him. Is this emptiness inherent, or a product of his mediated existence? Haneke leaves that uncomfortable question hanging.

The Architecture of Denial

Just as compelling, and perhaps even more tragically resonant, are the performances of Benny’s parents, played by the brilliant Angela Winkler and the late, great Ulrich Mühe (unforgettable years later in The Lives of Others, 2006). When confronted with the horrifying reality of their son's actions (discovered, inevitably, via videotape), their reaction is not immediate horror or grief, but a calculated, almost bureaucratic response focused on containment and self-preservation. Their dialogue becomes clipped, pragmatic, focused on logistics rather than morality. Mühe and Winkler portray this parental failure with devastating subtlety. We see flickers of panic beneath the surface, but their overriding instinct is to manage the situation, to erase the problem, embodying a bourgeois society more concerned with maintaining appearances than confronting ugly truths. Their complicity becomes almost as chilling as Benny’s initial act.

Fragments of a Cold World

Benny’s Video forms the second part of what Haneke termed his "Glaciation Trilogy," alongside The Seventh Continent (1989) and 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance (1994). These films share a thematic concern with emotional alienation and the breakdown of communication in modern society. Haneke wasn't interested in easy answers or psychological explanations. He famously resisted interpreting his own work, preferring to present the audience with uncomfortable scenarios and force them to grapple with the implications. The film garnered acclaim, including the FIPRESCI Prize at the 1992 Cannes Film Festival, but its starkness undoubtedly alienated some viewers expecting more conventional thrills or resolutions. Finding challenging works like this back in the VHS days often felt like an act of discovery – seeking out those unusual spine designs in the less-trafficked aisles of the rental store, hoping for something that pushed boundaries. Benny's Video certainly did that. The integration of the video footage itself within the film – often showing Benny watching his recordings on monitors within the frame – was a potent meta-commentary on spectatorship, even back in '92.

The Persistent Buzz

Decades later, the film feels disturbingly prescient. In an age saturated with screens, where shocking events can be captured, shared, and consumed with increasing detachment, Benny’s chilling relationship with his camcorder resonates profoundly. It forces us to question our own consumption of images, particularly violent ones. Does the barrier of the screen create distance? Does it numb us? Haneke offers no easy answers, only the unsettling portrait of a boy, his camera, and the void that separates them from genuine human feeling. It’s not a film you "enjoy" in the typical sense; it’s one you endure, absorb, and wrestle with. I remember renting this tape, likely drawn by some intriguing cover art or a cryptic synopsis, and feeling that distinct chill – the sense that cinema could be more than entertainment, that it could be a direct, uncomfortable confrontation.

Rating: 8/10

Benny's Video earns this score not for being pleasant, but for its artistic rigor, its uncompromising vision, and its lasting thematic power. Haneke's direction is masterful in its control and purpose, and the performances, particularly from Frisch, Winkler, and Mühe, are pitch-perfect in their portrayal of alienation and moral compromise. It's deliberately paced and emotionally cold, which can be challenging, but this detachment is precisely the point. It’s a vital, disturbing piece of 90s art cinema that remains relevant.

It leaves you with a lingering disquiet, the hum of the television screen echoing long after the credits roll, forcing you to consider the unblinking eyes – both Benny's and our own.