The glare off the asphalt could almost burn your eyes out. Not the neon-slicked noir of classic Hollywood, but the harsh, unforgiving sun of industrial Los Angeles. That's the first thing that hits you about City of Industry (1997) – its bleached-out, oppressive sense of place. This isn't a film noir shrouded in romantic shadow; it's a crime story stripped bare, baked under the California sky, leaving only sweat, desperation, and the metallic tang of impending violence. It’s the kind of movie that felt heavy in your hands even as a VHS tape, hinting at the brutal weight within.

Concrete Jungle Payday

The setup is classic hardboiled: a jewel heist planned with meticulous care by veteran thief Roy Egan (Harvey Keitel) and his impulsive younger brother, Lee (Timothy Hutton). They bring in hothead driver Skip Kovich (Stephen Dorff) and seasoned muscle Jorge Montana (Wade Dominguez). Predictably, greed curdles the score. Skip decides he wants the whole take, leading to a bloody betrayal that leaves Roy wounded, his brother dead, and a burning need for vengeance consuming him. What follows isn't a flashy action spectacle, but a slow, methodical hunt through the underbelly of L.A., fuelled by Roy’s cold, calculating fury.

Keitel's Quiet Fury

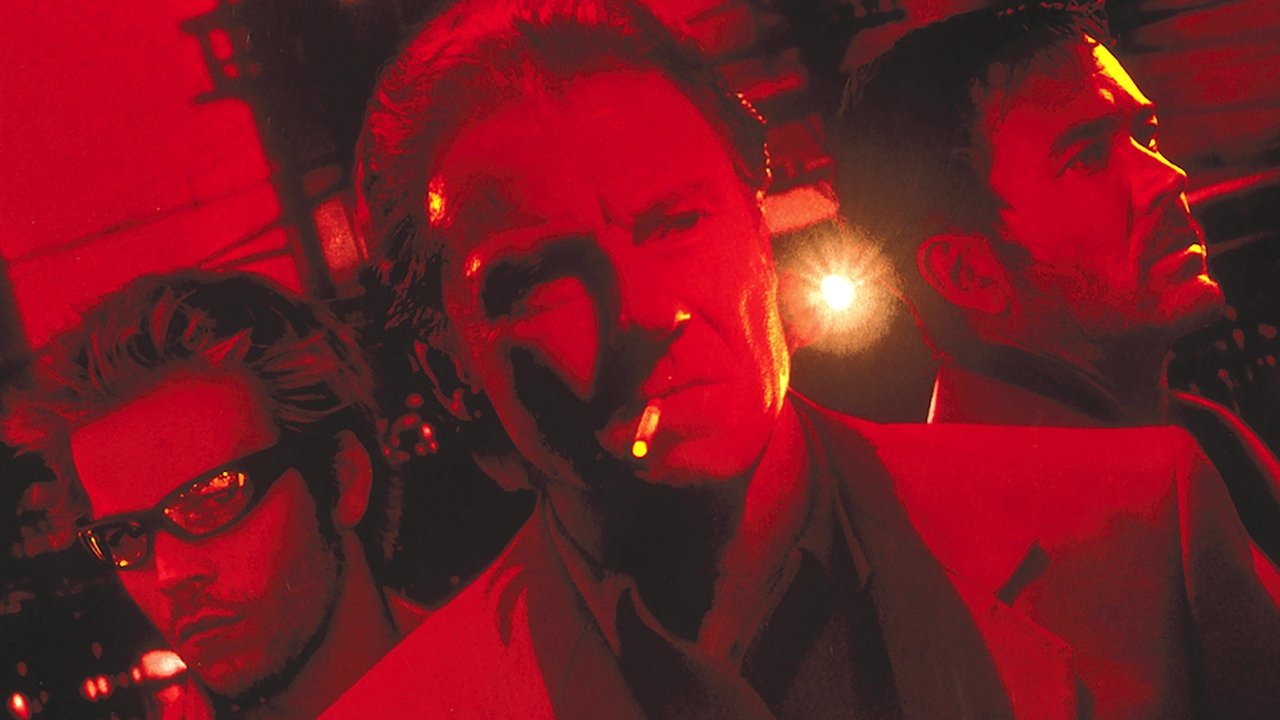

Let's be clear: Harvey Keitel is this movie. Already a legend for inhabiting complex, often dangerous men in films like Reservoir Dogs (1992) and Bad Lieutenant (1992), Keitel brings a profound weariness and coiled intensity to Roy. He's a professional in a world rapidly losing any sense of code. His movements are deliberate, his words sparse, but his eyes convey reservoirs of controlled rage. Watching him operate – casing Skip’s associates, gathering information, preparing for the inevitable confrontation – is a masterclass in understated menace. It's a performance that anchors the film's grim reality. Opposite him, Stephen Dorff, then a rising star on the cusp of hitting bigger with Blade (1998), perfectly embodies the reckless arrogance of Skip. His jittery energy and explosive temper make him a genuinely unsettling antagonist. The contrast between Keitel's quiet burn and Dorff's loud volatility creates sparks whenever they share the screen, or even when they're just hunting each other. Timothy Hutton, an Oscar winner for Ordinary People (1980), has less screen time but effectively portrays the hesitant vulnerability of Lee, making his fate hit harder.

Grinding Gears of Production

Directed by John Irvin, a filmmaker familiar with gritty realism from war films like Hamburger Hill (1987) and the slightly more pulpy action of Raw Deal (1986), City of Industry feels purposeful in its ugliness. Irvin uses the sprawling, impersonal landscape of warehouses, freeways, and cheap motels to create a sense of alienation and moral decay. There’s little beauty here, only function and grime. The lean, mean script by Ken Solarz (sadly, one of his few major credits before his untimely death) avoids unnecessary subplots, focusing squarely on Roy's quest. It’s refreshingly straightforward, recalling the brutal efficiency of classic crime paperbacks. The violence, when it erupts, is sudden, clumsy, and impactful – less choreographed ballet, more desperate struggle. This commitment to unvarnished reality reportedly came from Irvin's demanding style; he wanted the grit to feel earned, pushing for a realism that bleeds through the screen, making the relatively modest $8 million budget stretch effectively into a tense viewing experience.

A Sun-Bleached Noir Vibe

The film’s atmosphere is thick enough to choke on. Stephen Endelman's score pulses with a low, ominous thrum, rarely swelling into traditional melodrama, instead underscoring the constant, simmering tension. The cinematography emphasizes harsh light and deep shadows even in daylight, framing characters against indifferent industrial backdrops. It’s a specific flavour of 90s neo-noir – less concerned with existential dread than with the practical, brutal consequences of bad choices in a world devoid of easy outs. Remember picking this one up from the video store shelf? Maybe the cover art, with Keitel looking resolute, promised a straightforward revenge flick. What you got was something bleaker, more patient, and ultimately more chilling than expected. Doesn't that slow-burn pursuit still feel remarkably tense?

Lasting Impression

City of Industry isn't perfect. Some supporting characters feel underdeveloped, and the plot, while efficient, holds few genuine surprises. Yet, its strengths are considerable. It’s a remarkably focused and atmospheric piece of filmmaking, anchored by Keitel's magnetic central performance and Irvin's commitment to a stark, unglamorous vision of crime. It doesn't offer redemption or easy answers, just the grinding inevitability of violence and consequence. It never achieved massive success (grossing under $2 million domestically), making it a prime candidate for rediscovery by fans digging for potent 90s crime thrillers beyond the usual suspects.

VHS Heaven Rating: 7/10

Justification: While the narrative trajectory is somewhat predictable and character depth beyond the leads is limited, City of Industry excels in its oppressive atmosphere, gritty realism, and features a powerhouse performance from Harvey Keitel. Its commitment to a bleak, unvarnished tone makes it a standout example of mid-90s neo-noir, effective in its brutal simplicity.

Final Thought: In the landscape of 90s crime films, City of Industry might be less flashy than Pulp Fiction or less complex than Heat, but its stark, sun-baked brutality leaves a unique and unsettling residue – a dusty, blood-stained artifact from the shelves of VHS Heaven.