Sometimes, a film settles over you not like a comforting blanket, but like the humid, inescapable heat of a summer afternoon where something bad feels destined to happen. That's the lingering sensation of Steven Soderbergh's 1995 neo-noir, The Underneath. It wasn't a tape that flew off the rental shelves, perhaps overshadowed by splashier fare, but finding it nestled amongst the thrillers always felt like unearthing something... different. It carries the distinct weight of a filmmaker wrestling with expectation and perhaps his own ambivalence, creating a mood piece that sticks with you, even if it doesn’t entirely embrace you.

A Past You Can't Outrun

The setup feels classic noir: Michael Chambers (Peter Gallagher) drifts back into his hometown of Austin, Texas, ostensibly for his mother's wedding. But like any good noir protagonist, he's trailing a cloud of past mistakes. He skipped town years ago, leaving behind debts, a broken marriage to Rachel (Alison Elliott), and the wreckage caused by his gambling addiction. His return isn't just about seeing family; it's an unavoidable collision course with the life he abandoned. Rachel is now entangled with the menacing local hoodlum Tommy Dundee (William Fichtner), and Michael, inevitably, finds himself drawn back into her orbit, setting the stage for a heist doomed from the start. It’s a premise borrowed directly from Don Tracy's novel Criss Cross, famously adapted by Robert Siodmak in 1949, and you can feel Soderbergh grappling with the shadow of that classic.

Filtered Reality, Fractured Time

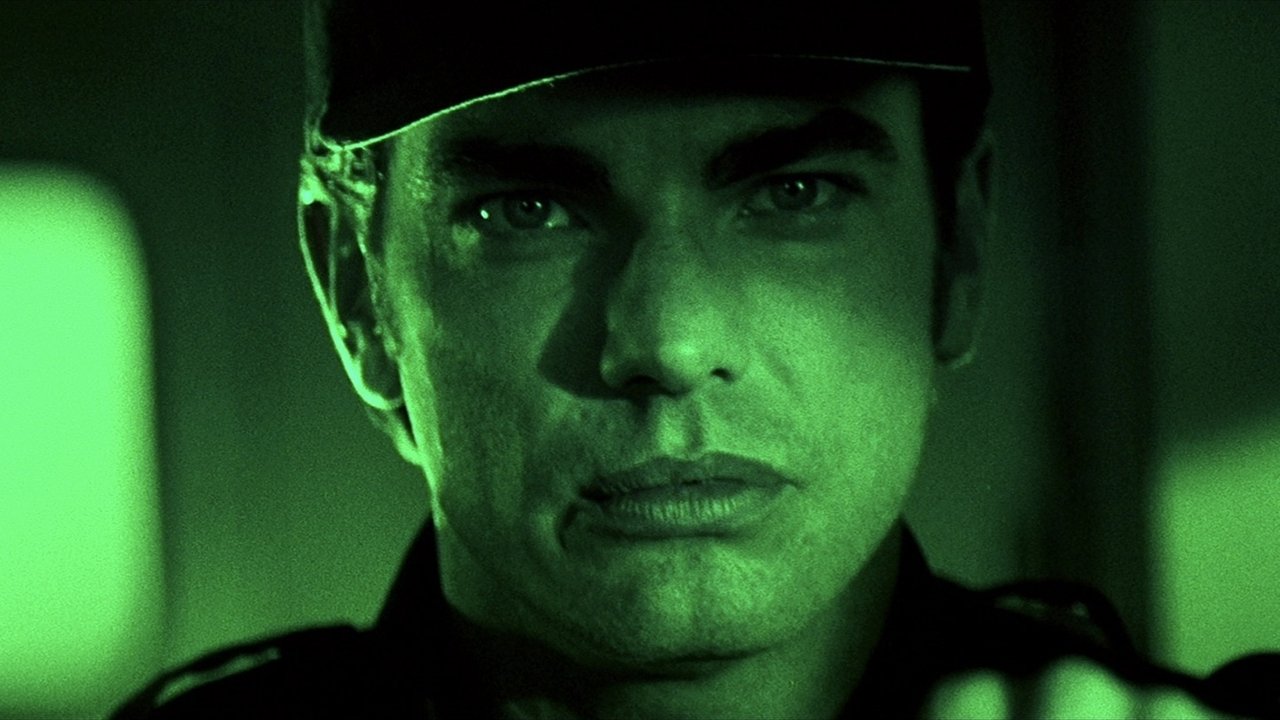

What immediately sets The Underneath apart is its visual language. Working with cinematographer Elliot Davis, Soderbergh drenches Austin in stylized, often unnatural colours – deep blues, sickly greens, intense oranges – reflecting Michael's distorted perception and the morally ambiguous world he navigates. The film eschews a straightforward narrative, instead adopting a fragmented, non-linear structure, heavily influenced by filmmakers like Nicolas Roeg (Don't Look Now). We jump between Michael's present predicament, his memories of happier times with Rachel before his fall from grace, and flash-forwards hinting at the inevitable violent outcome. This fractured timeline isn't just a stylistic flourish; it mirrors Michael's own fractured psyche and the sense that past, present, and future are tragically intertwined and inescapable. It forces the viewer to piece things together, enhancing the feeling of disorientation and impending doom. Does this deliberate distancing always serve the emotional core? That’s debatable, and perhaps contributes to the coolness some critics noted at the time.

Faces in the Glare

Peter Gallagher, an actor always capable of conveying charm laced with weakness, embodies Michael's self-destructive nature well. He's not entirely unsympathetic, but Soderbergh doesn't let him off the hook easily. We see the appeal he holds for Rachel, but also the inherent selfishness that led him down this path. Alison Elliott, then a relative newcomer, brings a captivating ambiguity to Rachel. Is she a victim trapped by circumstance, or does she possess a shrewder, more calculating side? The film leaves her motivations deliberately opaque, making her a true femme fatale for the 90s – less overtly manipulative, perhaps, but no less dangerous to Michael's precarious existence.

But let's be honest, the performance that often electrifies discussions about The Underneath belongs to William Fichtner. As Tommy Dundee, he’s not just a stock villain; he radiates a coiled, unpredictable menace. Fichtner, who would go on to become one of cinema's most reliable character actors (think Heat (1995) or Armageddon (1998)), imbues Tommy with a chilling charisma and an undercurrent of violence that feels utterly real. Every scene he's in crackles with tension. It's a star-making turn in a film that otherwise keeps its emotions at arm's length.

A Director's Detour

It’s impossible to discuss The Underneath without acknowledging Steven Soderbergh's own documented feelings about it. Coming off the seismic success of Sex, Lies, and Videotape (1989), the pressure was immense. He took on this project, a studio assignment, partly out of a desire to work again but has since described it as a formative, if difficult, experience. He's openly called the film "cold" and admitted feeling constrained by the remake structure. Knowing this adds a fascinating layer – are we seeing the film's detached tone as a deliberate artistic choice, or as a reflection of the director's own disengagement? Maybe it's a bit of both.

This context perhaps explains its muted reception. With a budget around $6.5 million, it barely made a dent at the box office, grossing just over half a million dollars domestically. It screened in the Un Certain Regard section at Cannes but generated little buzz. For many, it became a curious footnote between his indie breakthrough and his later resurgence with films like Out of Sight (1998). Yet, watching it now, especially with Cliff Martinez's typically moody and effective score pulsing underneath, it feels like a vital, albeit flawed, step in his journey, experimenting with style and narrative in ways that would inform his later, more acclaimed work. The challenges were real; Soderbergh even re-edited the film slightly after its festival debut, trying to find its elusive rhythm.

Lingering Shadows

The Underneath isn't a film that provides easy answers or cathartic release. It's a mood piece, thick with atmosphere and a sense of predetermined failure. It captures that specific 90s indie sensibility – stylish, introspective, and a little chilly. It might not be the hidden gem you champion to everyone, but for fans of neo-noir, Soderbergh completists, or those who appreciate a film that prioritizes mood over plot mechanics, it holds a certain melancholic allure. It’s a reminder that sometimes the most interesting journeys are the detours.

Rating: 6/10

Justification: The film boasts a compelling atmosphere, striking visuals, and a standout performance from William Fichtner. Soderbergh's stylistic experimentation is evident and intriguing. However, its deliberate coldness and non-linear structure can sometimes feel distancing, preventing deeper emotional engagement, a point the director himself seems to concede. It’s a technically proficient and atmospheric film, but one that feels more like an interesting exercise than a fully realized emotional journey.