The boot hits the floor first. Not with a thud, but a sharp, sterile click. Then the bewildered face, the identical room stretching out in every direction, differentiated only by the cold hue of the light. There's no exposition, no establishing shot of a city skyline, no comforting voiceover. You, like the characters, are simply there, thrust into a geometric nightmare with no map and no memory of arrival. That sudden, disorienting plunge is the dark magic of Vincenzo Natali's 1997 sci-fi horror puzzle box, Cube. Forget elaborate monsters; the true terror here is the suffocating architecture of the unknown.

### Symmetry of Dread

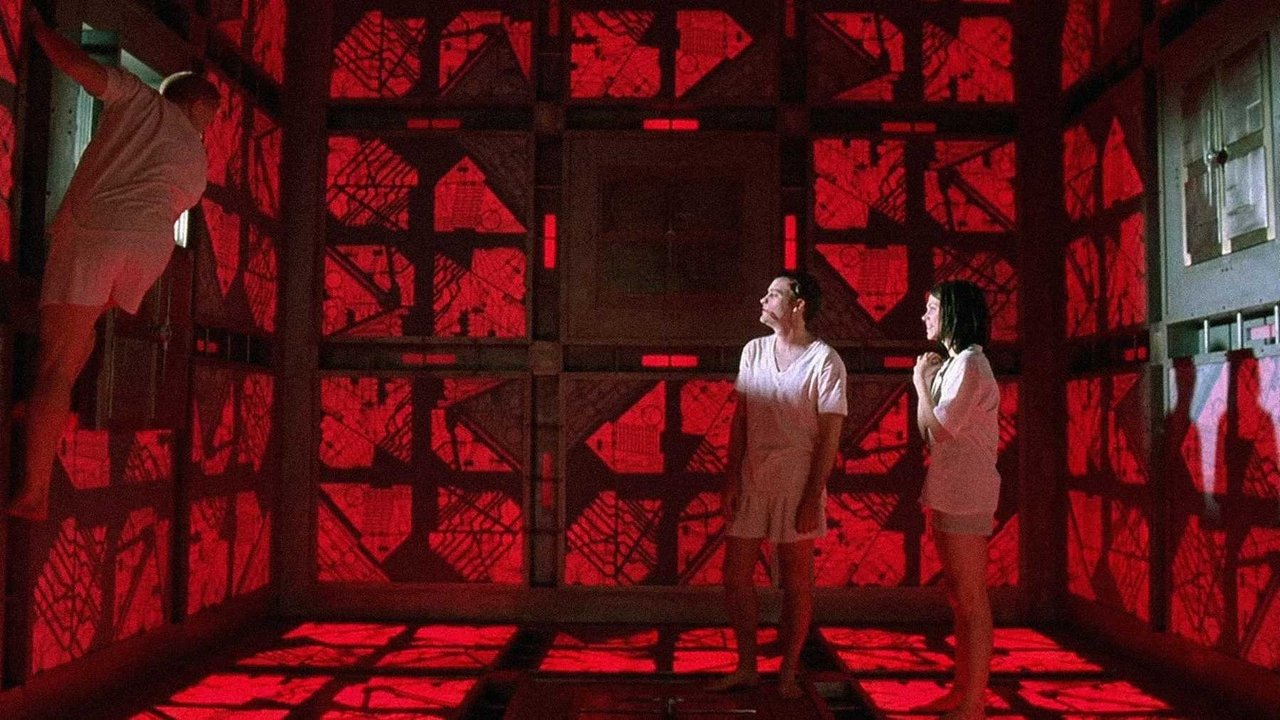

From the opening moments, Cube masterfully cultivates a palpable sense of claustrophobia and paranoia. The production design is deceptively simple yet profoundly effective. It's a masterclass in minimalist dread, a feeling amplified if you, like me, first encountered this film on a grainy VHS tape rented from a flickering corner store shelf. The identical, interconnected rooms, shifting in colour and occasionally containing lethal surprises, create a disorienting labyrinth that feels both infinite and crushingly confined. The stark industrial aesthetic, born partly from necessity due to its famously tight budget (around CAD $350,000 – a pittance even then), becomes one of its greatest strengths. You feel the cold metal, the humming machinery, the utter lack of organic comfort. Mark Korven's sparse, unnerving score doesn't try to orchestrate cheap jumps; it seeps under your skin, enhancing the grinding tension and the ever-present question: what lies through the next hatch?

### Faces in the Maze

Trapped within this existential Rubik's Cube are a handful of strangers, seemingly chosen at random, each embodying a familiar archetype yet slowly revealing deeper complexities under duress. There's Quentin (Nicky Guadagni), the tough cop whose authority quickly curdles into aggression; Holloway (Nicole de Boer, who would later navigate the final frontier in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine), the pragmatic doctor grappling with conspiracy; Worth (David Hewlett, in a role that showcased the nervous energy he'd later bring to Stargate Atlantis), the disillusioned architect who might hold a key, if only metaphorically; Leaven (Nicole de Boer), the young math whiz whose numerical talents become their only guide; Rennes (Wayne Robson), the seasoned escape artist known as 'The Wren'; and Kazan (Andrew Miller), the autistic savant whose unique perspective proves unexpectedly vital.

Their interactions are the film's raw, beating heart. As the initial shock wears off, alliances form and fracture with brutal speed. The true horror isn't just the ingeniously nasty traps lurking in certain rooms, but watching basic humanity erode under pressure. Vincenzo Natali, along with co-writers André Bijelic and Graeme Manson, doesn't shy away from the ugliness that emerges when survival instincts clash with paranoia and desperation. Did that rapid descent into mistrust feel chillingly believable even back then?

### The Devil in the Details

Part of Cube's enduring appeal lies in its puzzle-box nature. The Cartesian coordinates, the prime numbers – Leaven's frantic calculations provide fleeting moments of hope, a sense that logic might prevail over this brutalist nightmare. It’s a narrative engine that keeps you leaning forward, trying to crack the code alongside the characters. What many viewers didn't realize back in the day was the clever filmmaking trickery involved. Reportedly, the illusion of a vast, complex structure was achieved using primarily one 14x14x14 foot cube set, ingeniously redressed and re-lit, with different panel sections swapped out to create variety. Talk about making limitations work for you!

And those traps… while perhaps not boasting blockbuster SFX budgets, their impact was visceral, precisely because they felt so cruelly mechanical. The slicing wire grid, the sound-activated room, the acid spray – they were sudden, impersonal, and terrifyingly plausible within the film's logic. They tapped into that primal fear of unseen, automated death. It's also a darkly fitting detail that the characters' names – Quentin, Holloway, Worth, Leaven, Rennes, Kazan – are all names of real-world prisons. A grim piece of trivia that underscores the film's central theme of inescapable confinement. Natali himself cited influences like The Twilight Zone and the existential dread of Sartre, aiming for a Kafka-esque nightmare rather than a simple monster movie.

### Echoes in the Corridor

Cube wasn't a massive box office smash initially, but it found its audience – the late-night renters, the festival crowds (winning Best Canadian First Feature at TIFF '97), the word-of-mouth converts. It became a quintessential cult classic of the 90s, a film whose stark premise and chilling ambiguity resonated deeply. Its DNA can be seen in countless contained thrillers that followed, most notably the Saw franchise, though Cube trades torture-porn explicitness for a colder, more existential brand of horror. It spawned its own sequels (Cube 2: Hypercube, Cube Zero) and even a recent Japanese remake, proving the enduring power of its core concept.

The film wisely refuses to over-explain. Who built the Cube? Why these specific people? The lack of answers is precisely the point. Is it a government experiment gone rogue? An alien construct? A metaphorical hell? The ambiguity makes the horror personal, allowing viewers to project their own fears onto its sterile, deadly surfaces. It remains a testament to how much tension and terror can be wrung from a simple premise, sharp writing, committed performances, and resourceful direction.

---

Rating: 8.5/10

Cube earns its high score for being a triumph of minimalist filmmaking. It crafts unbearable tension and existential dread from a single, ingenious location, relying on sharp character dynamics and a chillingly ambiguous premise rather than excessive gore or complex effects. Its influence is undeniable, and its power to unsettle remains potent decades later. While the acting occasionally dips into the theatrical, the core concept and relentless atmosphere make it a standout piece of 90s sci-fi horror.

Final Thought: More than just a puzzle, Cube is a stark reminder that sometimes the most terrifying prisons are the ones we don't understand, built by forces unknown, forcing us to confront the darkness not just in the walls around us, but within ourselves. It's a film that, once seen, tends to lock itself inside your mind.