It starts not with a bang, but with a chillingly plausible whisper of the future. Imagine a world largely cured of fatal disease, where death itself has become a rare, almost exotic spectacle. Now imagine television producers hungry for ratings deciding that the raw, unvarnished process of dying is the ultimate reality show. This isn't some far-flung dystopia; it’s the unnerving heart of Bertrand Tavernier's 1980 film Death Watch (La Mort en direct), a movie that feels less like science fiction now and more like a documentary filmed just slightly ahead of its time.

Seeing it again after all these years, tucked away perhaps between more bombastic sci-fi rentals on the video store shelf, its quiet power feels even more profound. It lacks the laser battles or gleaming chrome futures often associated with the genre in that era. Instead, Tavernier, a director deeply immersed in film history (he’d later give us the sublime 'Round Midnight (1986)), crafts something far more unsettling: a future that looks remarkably like our weary present, just with one horrifying technological twist.

A City as Character

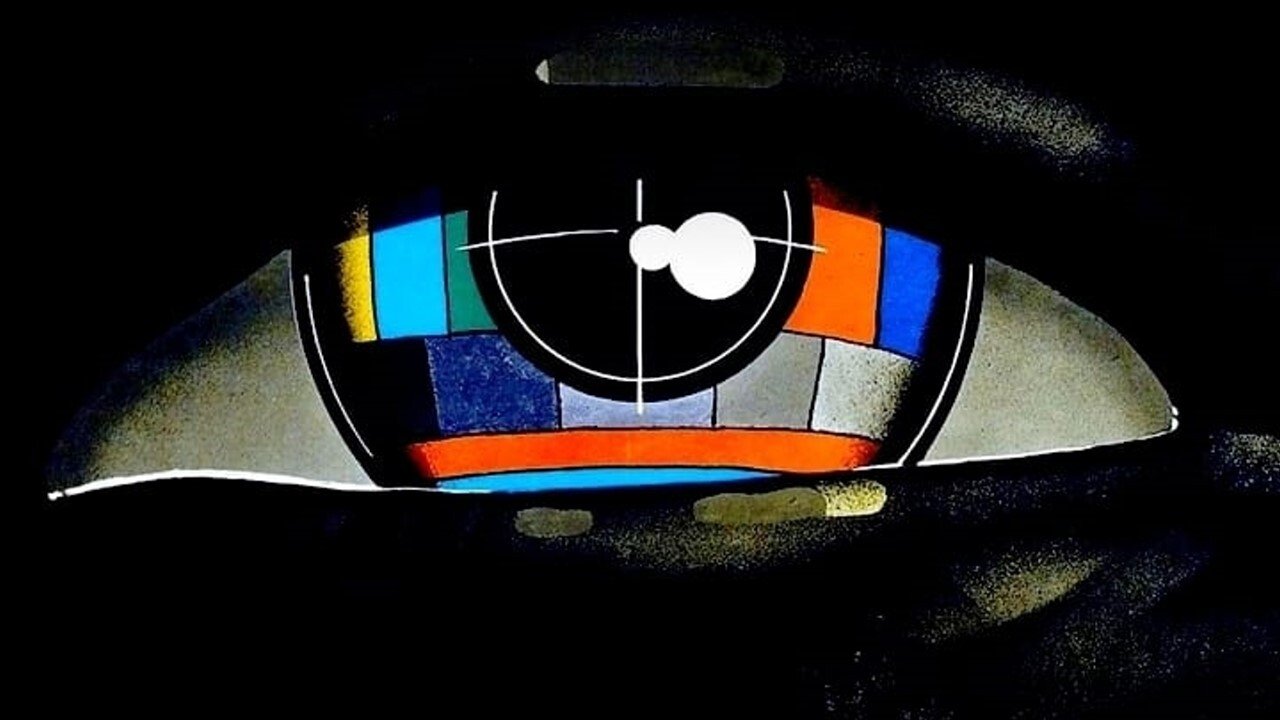

The film sets its stage not in some gleaming metropolis, but amidst the beautifully decaying industrial grandeur of Glasgow, Scotland. This choice, made deliberately by Tavernier to avoid sci-fi clichés and ground the story, is inspired. The crumbling architecture and overcast skies perfectly mirror the internal state of Katherine Mortenhoe (Romy Schneider), a woman who receives the devastating news that she has a rare, incurable disease and only weeks to live. Her plight immediately attracts the attention of Vincent Ferriman (Harry Dean Stanton), a cynical television executive who sees her impending death as the ultimate unmissable television event. Enter Roddy (Harvey Keitel), a cameraman who has undergone a radical procedure: miniaturized cameras have been implanted directly into his eyes. His mission? To befriend Katherine, shadow her every move, and broadcast her final moments to a morbidly fascinated public, all without her knowledge.

Watching Harvey Keitel, an actor always willing to plumb uncomfortable depths (think Bad Lieutenant (1992) a decade later), navigate this role is fascinating. He’s not just playing a character; he is the invasive lens. The strain is palpable – the need to keep his eyes open, the constant awareness of broadcasting, the dawning horror of his complicity. It’s a unique acting challenge, portraying a man whose very gaze is a betrayal, and Keitel conveys the internal conflict with minimalist, yet powerful, intensity. Apparently, the production had to sometimes manipulate lighting specifically to deal with the reflections that might give away the fact Keitel wasn't just looking, but recording.

The Unbearable Weight of Being Watched

At the film's core lies the devastating performance of Romy Schneider. As Katherine, she embodies a quiet dignity shattered by an unimaginable violation. She isn't just battling a disease; she's fighting for the last vestiges of her privacy and humanity against an unseen, omnipresent audience. Schneider, already a screen legend in Europe, brings a profound vulnerability and weariness to the role that is almost unbearable to watch, especially knowing the actress's own tragic personal circumstances that would follow just a couple of years later. Her scenes with Roddy are thick with dramatic irony – she seeks solace in the very person who represents her ultimate exploitation. Doesn't that dynamic raise uncomfortable questions about the nature of trust and connection in a mediated world?

Harry Dean Stanton, meanwhile, is perfectly cast as the embodiment of detached corporate cynicism. His Ferriman isn't a moustache-twirling villain; he’s worse – a pragmatist who genuinely believes he’s giving the public what they want, justifying the grotesque intrusion as some form of public service. It's a chillingly recognizable type, even more so now than perhaps in 1980. And a brief but crucial appearance by the legendary Max von Sydow adds another layer of gravitas.

Prophecy in Lo-Fi

What makes Death Watch resonate so strongly today is its startling prescience. Made years before the explosion of reality television, it perfectly predicted the ethical quagmire and audience appetite for "unfiltered" human experience, no matter the cost. Tavernier wasn't interested in flashy effects; the film’s budget was modest, and its power comes from the performances and the chillingly simple concept. The only real futuristic tech is Roddy's camera eyes – everything else feels grounded, almost depressingly familiar. Tavernier uses the Glasgow setting, the run-down pubs and windswept landscapes, to create an atmosphere of weary authenticity. This isn't the future as spectacle, but the future as a continuation of human folly, amplified by technology.

The film reportedly struggled to find a wide audience initially, perhaps its bleakness and intellectual rigor were out of step with the escapism often sought in early 80s sci-fi. Yet, its reputation has steadily grown, achieving a kind of cult status among cinephiles who recognize its uncomfortable truths. It forces us to confront our own complicity as viewers. When we watch reality TV, scroll through social media feeds documenting personal struggles, where do we draw the line? What is the ethical cost of our insatiable curiosity?

Rating & Final Reflection:

Death Watch isn't an easy watch. It’s a slow-burn, thoughtful, and deeply melancholic film that burrows under your skin. The pacing might test those looking for action, but the performances, particularly Schneider's heartbreaking turn, are unforgettable. Tavernier's direction is intelligent and restrained, allowing the horrifying implications of the premise to speak for themselves. The film’s foresight regarding media ethics and voyeurism is simply stunning. It’s a vital piece of 80s cinema that feels more relevant with each passing year.

Rating: 9/10

Justified by its powerful and tragically resonant lead performance from Romy Schneider, Harvey Keitel's unique portrayal of the 'camera man', its startlingly prescient themes that predicted the rise of intrusive reality media, and Bertrand Tavernier's intelligent, atmospheric direction that grounds the sci-fi concept in uncomfortable reality. The slightly deliberate pacing might be the only minor point preventing a perfect score for some viewers expecting faster genre fare.

It leaves you not with answers, but with lingering questions about empathy, exploitation, and the ghosts in the machine – both the literal cameras in Roddy’s eyes and the figurative ones we all carry in the age of constant observation. A haunting echo from the dawn of the VHS era, warning us about a future that arrived far too quickly.