It starts not with a bang, nor even a whimper, but with an unnerving, profound silence. That’s the image from Geoff Murphy’s The Quiet Earth (1985) that always sticks with me: Bruno Lawrence as Zac Hobson, waking to a world utterly devoid of people. No cars moving, no distant sirens, just the cold sunrise over an empty Auckland. It’s a chillingly effective opening, tapping into a primal fear of isolation far more potent than any monster or alien invasion flick clogging the rental shelves back in the day. Finding this gem, often tucked away in the less-trafficked aisles of the Sci-Fi section, felt like uncovering a secret – a thoughtful, unnerving piece of cinema that asked questions instead of just providing explosions.

Alone in the Playground

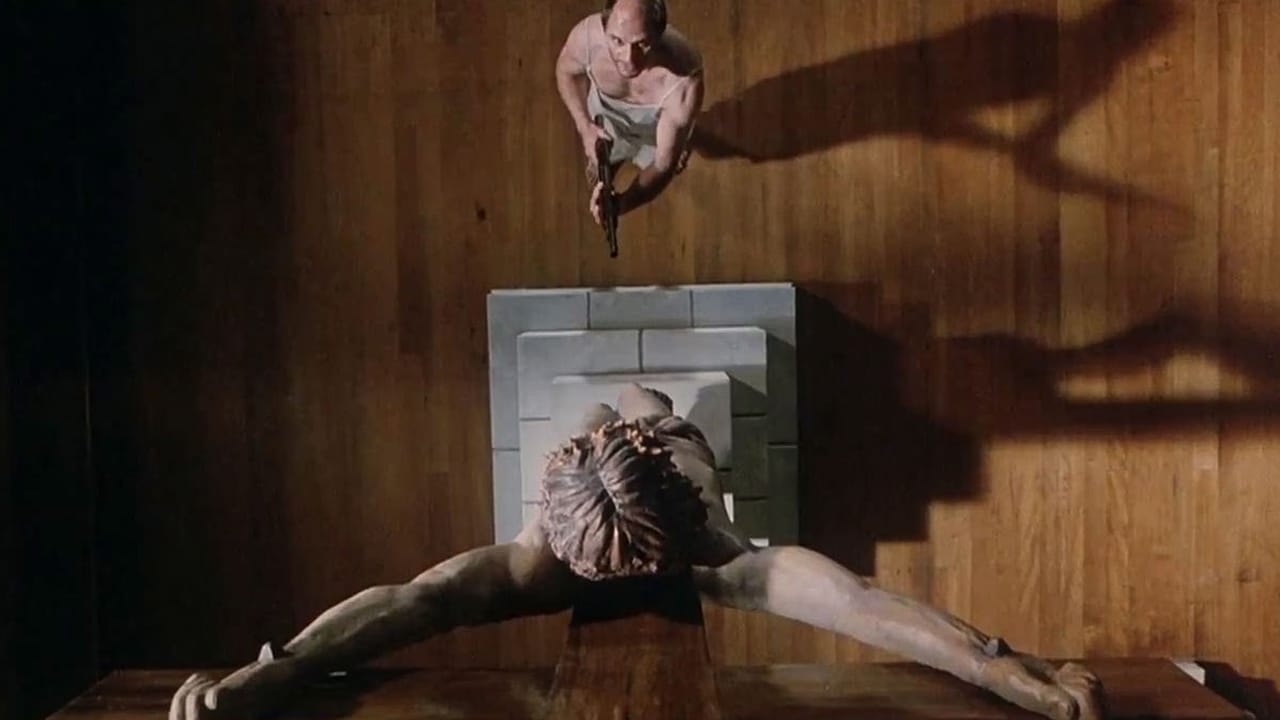

The film spends its first act immersed in Zac's solitude, and it's a masterclass in character study fueled by Bruno Lawrence’s astonishingly committed performance. Initially, there’s a manic energy – who wouldn’t indulge fantasies in an empty world? He moves into a mansion, addresses cardboard cutouts of historical figures, declares himself president of this "quiet Earth." It’s almost darkly funny, a desperate attempt to impose order on the inexplicable. But the facade cracks quickly. Lawrence brilliantly portrays Zac’s descent into despair, the loneliness gnawing at him until he’s teetering on the edge of sanity, culminating in a harrowing mock-suicide attempt with a shotgun in a deserted church. It’s raw, uncomfortable, and utterly believable. You’re right there with him, feeling the crushing weight of absolute silence. Was this what the end of the world truly felt like? Not fire and fury, but an endless, echoing void?

Echoes of Guilt and Hope

Of course, Zac isn't entirely alone forever. The arrival of Joanne (Alison Routledge) and later Api (Pete Smith) shifts the dynamic dramatically. The film transitions from pure survival horror into a complex, often uneasy, love triangle and a desperate search for answers. What was "The Effect"? Was Zac, a scientist involved in the very project that might have caused it, somehow responsible? The screenplay, adapted by Bill Baer, Sam Pillsbury, and original novelist Craig Harrison, doesn't spoon-feed easy answers. It delves into themes of guilt, responsibility, and the potential for redemption. Joanne represents a fragile hope for connection, while Api, a Maori man whose relationship with the land feels intrinsically different, brings a spiritual and grounded perspective. Their interactions are charged, layered, forcing Zac (and the audience) to confront the human flaws that might have led to this catastrophe in the first place.

Interestingly, the film was a product of the burgeoning New Zealand film industry finding its international voice, made for a relatively modest budget (around NZ$1 million). This constraint likely fueled its creativity. Director Geoff Murphy, who had already made waves with the Kiwi classic Goodbye Pork Pie (1981) and would later helm Hollywood fare like Young Guns II (1990) and Under Siege 2: Dark Territory (1995), uses the emptiness of real locations to stunning effect. Seeing familiar cityscapes utterly deserted holds an eerie power that expensive CGI often fails to replicate. There's a tangible sense of loss baked into the visuals.

Retro Fun Facts: Sounds of Silence and Cosmic Ripples

- Bruno's Score: Bruno Lawrence, already a respected musician (founder of the experimental group Blerta), actually co-composed parts of the film's unsettling electronic score, adding another layer of his personal investment to Zac's troubled psyche.

- Empty Streets Trick: Achieving those shots of deserted Auckland streets wasn't easy on a low budget. The crew often filmed very early on Sunday mornings, sometimes having to quickly block off streets for brief periods, relying on meticulous planning and perhaps a bit of luck.

- Novel Differences: While capturing the core dread, the film significantly alters the plot and ending of Craig Harrison's 1981 novel. The book is even bleaker and features different character dynamics.

- Kiwi Breakthrough: The Quiet Earth was a critical success in New Zealand, winning multiple awards, and helped put NZ cinema on the map internationally during the 80s film renaissance down under.

The Lingering Question

The performances are uniformly strong. Alison Routledge brings a necessary warmth and intelligence to Joanne, preventing her from becoming a mere plot device. Pete Smith as Api is quietly powerful, embodying a resilience and connection to the world that contrasts sharply with Zac's scientific detachment and guilt. But it's Bruno Lawrence's film. His portrayal of a man simultaneously brilliant, broken, arrogant, and desperate is captivating. It's a performance that stays with you, full of nuance and raw emotion.

And then there's the ending. (Minor Spoiler Warning!) That final, breathtaking shot – Zac alone on a beach, a bizarre Saturn-like planet hanging impossibly in the sky – is one of the great enigmatic endings in science fiction cinema. Is it another dimension? An afterlife? A symbol of cosmic consequence? The ambiguity is deliberate, leaving the viewer suspended in a state of wonder and unease. It doesn’t offer neat closure, instead prompting reflection long after the VCR clicked off. What responsibility do we bear for the tools we create? Can we ever truly escape ourselves?

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's powerful atmosphere, Bruno Lawrence's unforgettable central performance, its intelligent handling of profound themes, and its sheer uniqueness within the 80s sci-fi landscape. It overcomes its budget limitations through sheer ingenuity and emotional honesty. The pacing might feel deliberate compared to modern blockbusters, but its thoughtful exploration of isolation and consequence earns its place as a cult classic.

The Quiet Earth remains a haunting viewing experience, a quiet film that resonates loudly with questions about humanity's place in the universe and the echoes we leave behind. It’s a perfect example of the kind of thoughtful, character-driven science fiction that felt like a rare treasure discovered on the video store shelf.