The air hangs thick and damp, tasting of concrete dust and stale desperation. This isn't just a setting; it's the crushing weight of existence in Piotr Szulkin's 1985 masterpiece of despair, O-Bi, O-Ba: Koniec cywilizacji (or O-Bi, O-Ba: The End of Civilization). Forget sleek starships or laser battles; this is sci-fi stripped bare, plunged into the chilling depths of a subterranean bunker where humanity waits for a salvation that might only be a collective delusion. Watching this on a flickering CRT back in the day, likely from a worn-out VHS tape discovered in the dustier corners of the rental store, wasn't an experience easily shaken off. It burrowed under the skin, a bleakness that felt unnervingly real.

Echoes in the Concrete Tomb

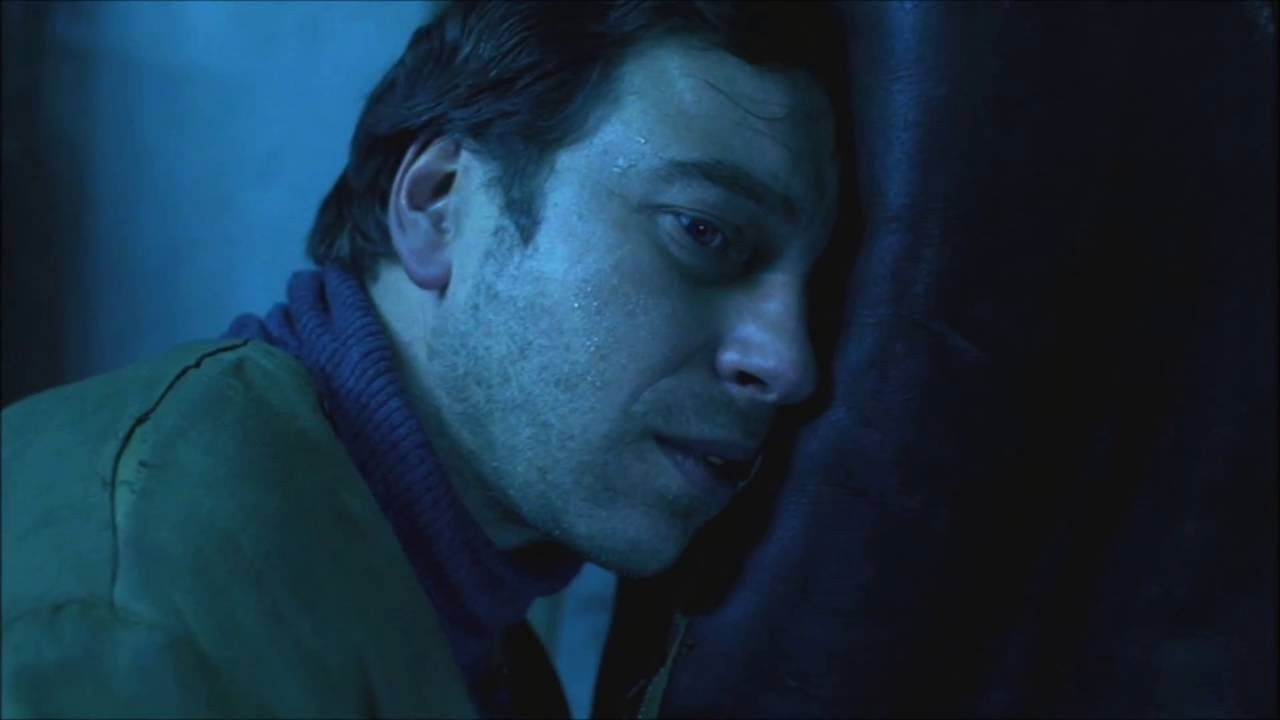

We're thrown into a dimly lit, decaying concrete hell somewhere in Poland, a year after a nuclear holocaust. The survivors huddle together, their lives governed by the pervasive, whispered promise of "The Ark" – a colossal vessel supposedly en route to rescue them. Keeping this fragile hope alive is Soft, played with soul-crushing weariness by the brilliant Jerzy Stuhr (a face familiar to many from Kieslowski’s Decalogue and Three Colors: White). Soft navigates the crumbling corridors, managing dwindling resources and reinforcing the myth, even as the very structure around them – and the belief system holding them together – seems ready to collapse. The genius of Szulkin's script and direction lies in its oppressive ambiguity. Is the Ark real? Does it even matter? The film suggests the lie might be the only thing keeping total anarchy at bay.

The Aesthetics of Decay

Forget glossy futures; O-Bi, O-Ba offers a masterclass in dystopian production design born from bleak necessity. The bunker isn't futuristic; it’s a crumbling, utilitarian nightmare. Water drips constantly, strange fungi bloom on damp walls, and the low, flickering light barely penetrates the oppressive shadows. This wasn't just an artistic choice; filming in Poland during the tense mid-80s, under the lingering shadow of martial law and with likely limited resources, Szulkin turned constraints into strengths. The decay feels authentic, lived-in, inescapable. It’s a chillingly effective visual metaphor for the erosion of spirit and truth. Watching it on VHS, the format’s inherent graininess and occasional tracking static somehow enhanced this feeling, making the image itself seem fragile, ready to dissolve like the hopes of the characters. Doesn't that specific kind of lo-fi dread feel unique to the era?

Hope as Opiate

The film is a stark allegory, a thinly veiled critique of the crumbling communist regime in Poland at the time. The Ark represents the hollow promises of ideology, a manufactured hope fed to the masses to ensure compliance and prevent total despair. Soft's role is that of the conflicted apparatchik, maintaining the system even as he grapples with its emptiness. Jerzy Stuhr embodies this conflict perfectly; his face a canvas of exhaustion, doubt, and the sheer effort of maintaining the facade. Opposite him, the ever-compelling Krystyna Janda (unforgettable in Andrzej Wajda's Man of Iron) as Gea adds a layer of desperate, searching humanity. The very title, O-Bi, O-Ba, sounds like meaningless babble, perhaps hinting at the emptiness of the slogans and myths propping up this subterranean society. It’s a political statement wrapped in the chilling cloak of post-apocalyptic sci-fi, smuggled past censors through metaphor and mood.

Szulkin's Dystopian Vision

O-Bi, O-Ba is the third film in Piotr Szulkin's loose tetralogy of dystopian visions, following Golem (1979) and Wojna światów – następne stulecie (The War of the Worlds: Next Century, 1981), and preceding Ga-ga: Chwała bohaterom (Ga-Ga: Glory to the Heroes, 1986). Each film explores themes of control, dehumanization, and societal breakdown with a uniquely bleak Eastern European sensibility. Szulkin wasn't interested in action; his focus was on the psychological and philosophical fallout of catastrophe and control. The tension here isn't derived from external monsters, but from the internal decay of hope and the oppressive weight of the environment. Finding a film like this on VHS felt like unearthing forbidden knowledge, a transmission from a world far removed from Hollywood gloss, yet disturbingly close in its exploration of human frailty.

The Lingering Chill

The film doesn’t offer easy answers or cathartic releases. Its power lies in its suffocating atmosphere and its refusal to compromise its bleak vision. The ending (no spoilers here, but brace yourself) is less a conclusion and more an echo of the film's central questions about truth, belief, and the human capacity for self-deception. It leaves you in the dark, literally and figuratively, pondering the fate of the bunker's inhabitants long after the tape clicked off. It’s a challenging watch, certainly not a Friday night popcorn flick, but its haunting imagery and potent allegory make it an unforgettable piece of 80s sci-fi, a testament to the power of filmmaking under pressure.

---

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects O-Bi, O-Ba's masterful creation of atmosphere, its powerful allegorical depth, Jerzy Stuhr's compelling lead performance, and its unforgettable, bleak production design. It's a near-perfect execution of its grim vision, docked only slightly because its challenging pace and unrelenting despair might not resonate with all viewers seeking conventional entertainment. However, as a piece of politically charged, atmospheric sci-fi, it's outstanding.

O-Bi, O-Ba: The End of Civilization remains a potent and chilling artifact of its time – a bleak broadcast from behind the Iron Curtain, wrapped in the guise of science fiction. It’s a film that truly captures the feeling of entrapment and the terrifying fragility of hope, a dark gem rediscovered from the depths of the VHS era.