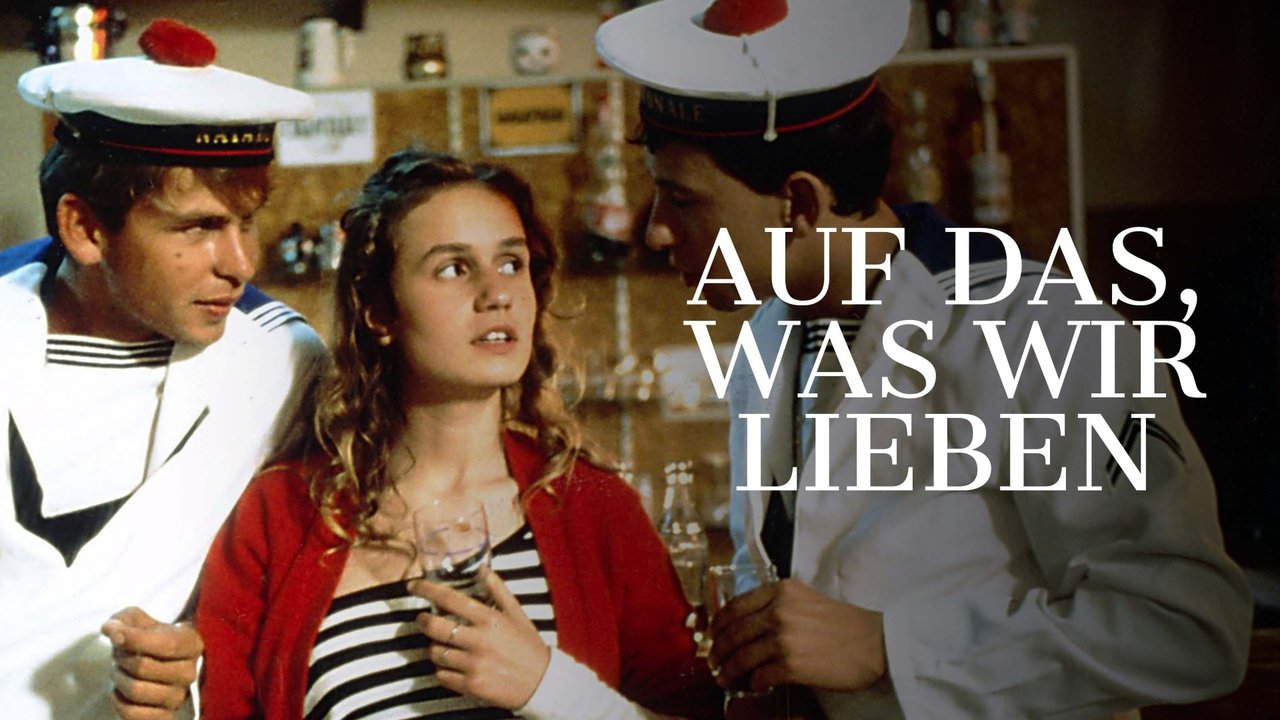

What lingers most profoundly after the credits roll on Maurice Pialat's À Nos Amours (1983) isn't a tidy plot resolution or a comforting message, but the raw, bruised feeling of having witnessed something intensely, uncomfortably real. It’s the cinematic equivalent of accidentally overhearing a furious family argument through a thin apartment wall, catching glimpses of vulnerability and rage that feel almost too private to observe. This wasn't the kind of film typically grabbing attention next to the action blockbusters on the video store shelves back in the day, but finding it felt like unearthing a hidden, sometimes difficult, truth about the turbulence of growing up and the chaotic nature of love, both familial and romantic.

An Unvarnished Portrait

At its heart, À Nos Amours follows Suzanne (Sandrine Bonnaire), a 15-year-old girl navigating the confusing landscape of burgeoning sexuality and suffocating family dynamics in suburban Paris. She drifts from one fleeting, often dispassionate sexual encounter to another, seeking connection or perhaps just sensation, while her home life simmers with resentment and unspoken tensions. Her volatile father (Maurice Pialat himself) and tightly wound mother (Evelyne Ker) preside over a household where affection is intertwined with aggression, and moments of tenderness can erupt into violence without warning. Pialat, working with co-writer Arlette Langmann, strips away cinematic artifice, presenting scenes with a documentary-like immediacy that can be both riveting and deeply unsettling.

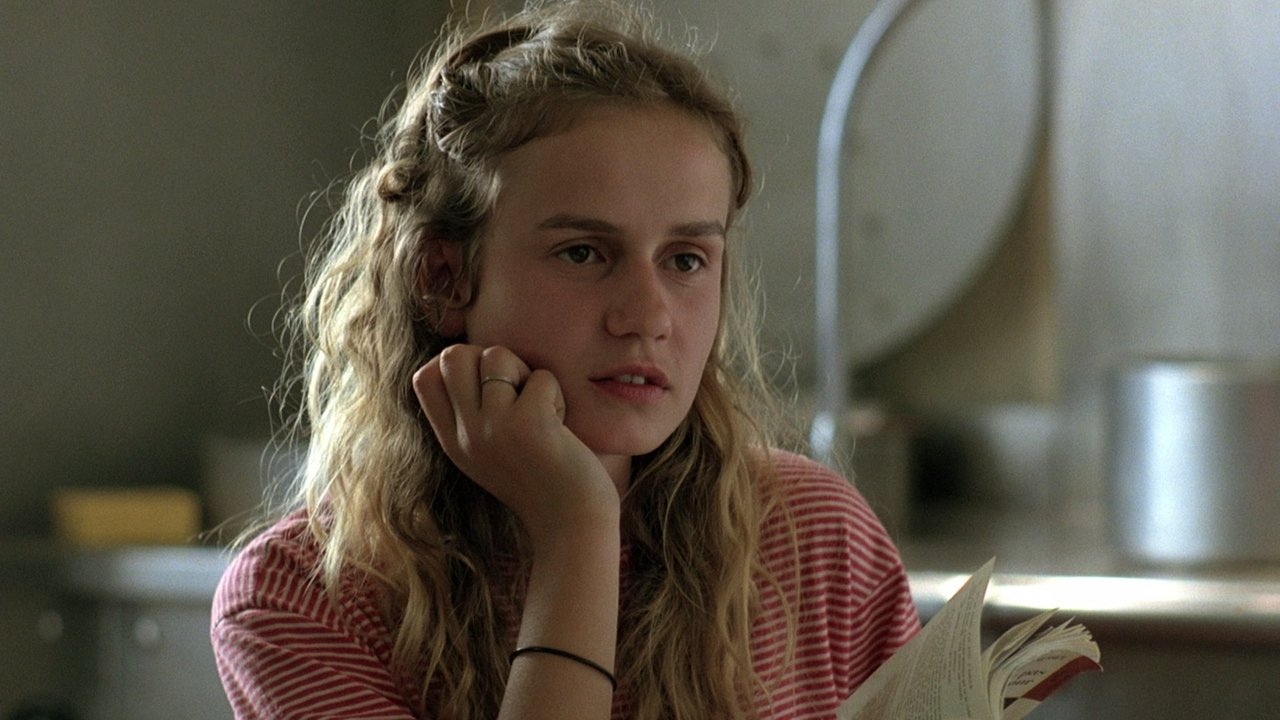

The Revelation of Sandrine Bonnaire

The film is utterly inseparable from the astonishing debut performance of Sandrine Bonnaire. Reportedly discovered through a casting call and just sixteen at the time of filming, Bonnaire embodies Suzanne with a naturalism that is simply breathtaking. There's no trace of practiced technique, only raw presence. She conveys Suzanne's mix of defiance, confusion, vulnerability, and emerging self-awareness often through subtle shifts in expression or posture rather than overt emoting. Watching her is like watching life unfold, unscripted. It’s a performance devoid of vanity, capturing the awkwardness and the sudden, startling moments of grace in adolescence. The fact that this wasn't a seasoned actress but a young woman thrust into this demanding role under Pialat’s notoriously challenging direction makes her achievement even more remarkable. It's no surprise she won the César Award for Most Promising Actress; it felt less like an award and more like a statement of fact.

Pialat: Provocateur and Patriarch

Maurice Pialat's decision to cast himself as the explosive, deeply troubled father adds another layer of fascinating, uncomfortable complexity. Pialat, known for his demanding methods and penchant for improvisation – pushing actors to find raw, authentic moments – doesn't shy away from portraying the father's flaws. He is magnetic, capable of warmth, but also terrifyingly unpredictable. His presence blurs the line between character and creator, making the family conflicts feel almost dangerously real. Was this Pialat the director pushing his actors, or Pialat the actor embodying a flawed man, or somehow, unsettlingly, both at once? This ambiguity fuels the film's power. He wasn't aiming for likability; he was aiming for truth, however jagged. This approach famously culminated in the legendary dinner party scene near the film's end – a sequence largely improvised, crackling with genuine tension and emotional fireworks, where Pialat unleashes a torrent of patriarchal frustration that feels utterly spontaneous and devastating. It’s a masterclass in controlled chaos.

Life Through a Fractured Lens

The film doesn't offer easy answers or clear motivations for Suzanne's behavior or her family's dysfunction. It presents moments, fragments of life, letting the viewer piece together the emotional landscape. The title, À Nos Amours ("To Our Loves"), feels almost ironic given the pain and difficulty surrounding relationships in the film, yet perhaps it speaks to the desperate, flawed attempts at connection, however brief or misguided. Pialat isn't interested in judging Suzanne's choices but in observing the often messy process of seeking intimacy and identity. The handheld camerawork and long takes contribute to this feeling of immediacy, of being trapped in these moments alongside the characters. It might lack the slick pacing of mainstream 80s fare, but its emotional honesty resonates far longer.

A Different Kind of VHS Discovery

Finding À Nos Amours on a dusty VHS tape, perhaps nestled in the "Foreign Language" section often overlooked by younger me hunting for the latest sci-fi epic, would have been a startling experience. It’s a film that demands patience and attention, rewarding the viewer not with escapism, but with a profound, sometimes bruising, reflection on the human condition. It stands as a cornerstone of 80s French cinema, a testament to Pialat’s uncompromising vision and the unforgettable arrival of Sandrine Bonnaire, who would go on to become one of France's most respected actresses, working with directors like Agnès Varda and Claude Chabrol. It’s a challenging film, yes, but its power lies precisely in its refusal to smooth over life's rough edges.

Rating: 8/10

This rating reflects the film's undeniable power, driven by Sandrine Bonnaire's landmark debut and Maurice Pialat's raw, confrontational style. Its unflinching honesty and documentary-like realism make it a challenging but deeply rewarding watch. It might not be a comfortable viewing experience, and its deliberate pacing and emotional intensity won't appeal to everyone seeking lighter fare from the era, keeping it from a higher score for general "VHS Heaven" enjoyment perhaps, but its artistic integrity and unforgettable performances make it a significant piece of 80s cinema.

À Nos Amours doesn't just depict troubled lives; it makes you feel the turbulent air in the room, the unspoken histories, the desperate search for love in its most complicated forms. It’s a film that gets under your skin and stays there, a potent reminder found on those magnetic tapes of cinema's power to confront, not just entertain.