It hits you almost immediately – not like a nostalgic wave, but like a clenched fist. There’s a raw, unvarnished intensity to 1983’s Bad Boys that feels worlds away from the synth-pop sheen coating much of the early 80s cinematic landscape. I remember sliding this tape into the VCR, perhaps expecting something closer to The Outsiders (released the same year), but finding instead a film that pulls no punches and refuses easy answers. It’s a movie that stays with you, less for its plot mechanics and more for the feeling it leaves behind: a knot in the stomach, a sense of unease about the brutal pragmatism of survival.

Into the Crucible

The setup is stark: Mick O'Brien, a young Chicago hoodlum simmering with unfocused rage, commits a crime born of recklessness and rivalry that ends in tragedy. The consequence isn't just jail time; it's Rainford Juvenile Correctional Facility, a place stripped of sentimentality, ruled by its own brutal codes. Director Rick Rosenthal, who stepped in after Roman Polanski's departure due to his ongoing legal battles, crafts an environment that feels genuinely dangerous. Forget Hollywood gloss; Rainford feels cold, metallic, and echoing with the constant threat of violence. The film doesn't shy away from the ugliness of institutional life, forcing us to confront the grim realities faced by these young men. Rosenthal, known then perhaps for the effective chills of Halloween II (1981), proves adept here at building tension not through jump scares, but through simmering hostility and the suffocating lack of escape.

The Arrival of Sean Penn

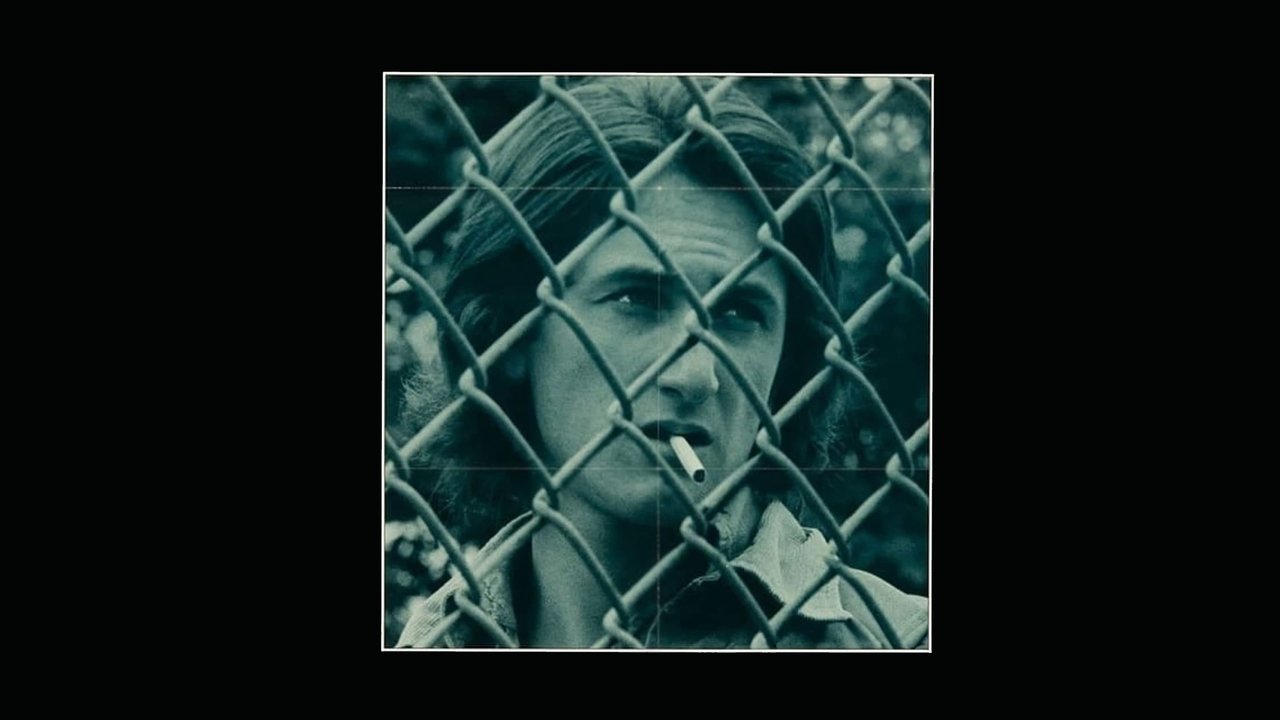

At the heart of this storm is a startlingly young Sean Penn as Mick. For many of us, Penn was Jeff Spicoli from Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982) – the perpetually stoned surfer dude. It's fascinating trivia that Bad Boys was actually filmed after Fast Times but released before it. Imagine the whiplash for audiences seeing this transformation! Penn doesn't just play Mick; he inhabits him with a ferocious energy that’s captivating and terrifying. There's a coiled danger in his eyes, a constant calculation behind the tough facade. Watch his body language – the wary posture, the sudden bursts of violence – it’s a performance devoid of vanity, focused entirely on the character's primal need to endure. He’s not asking for sympathy, merely understanding of the harsh choices his environment demands. It's a performance that announced the arrival of a major dramatic force, earning him considerable critical praise even then. How did he navigate the shift from Spicoli's laid-back haze to Mick's coiled intensity? It speaks volumes about his early range.

Faces in the Yard

The world of Rainford is populated by characters who feel disturbingly real, perhaps aided by the reported use of actual former young offenders as extras during filming at the St. Charles Youth Center near Chicago. Mick’s immediate nemesis within the facility is Horowitz (played with poignant vulnerability by Eric Gurry), his cellmate, whose perceived weakness makes him a target. Their complex relationship forms one of the film’s few fragile threads of humanity. But the shadow looming largest is Paco Moreno, played in a chillingly intense debut by Esai Morales. Paco, the vengeful brother of the boy Mick killed, lands in the same facility, bringing their street war inside the walls. Morales radiates a quiet, lethal menace; his presence raises the stakes exponentially. Their eventual confrontation is less a fight and more a primal explosion of hatred and desperation, staged with a brutal realism that feels earned, not gratuitous. That infamous scene involving a pillowcase and soda cans? It’s hard to shake, a visceral depiction of prison ingenuity turned deadly.

No Easy Lessons

What makes Bad Boys resonate, even decades later? It refuses to offer simple moral lessons or redemption arcs. Written by Richard Di Lello (perhaps better known for his insider account of The Beatles' Apple Corps, The Longest Cocktail Party), the script presents a cycle of violence where actions have devastating consequences, but survival often means perpetuating that cycle. Mick’s journey isn't about becoming "good"; it's about learning the brutal rules of the game and becoming strong enough, or perhaps hard enough, to play it. Even his connection to his girlfriend J.C. (an early role for Ally Sheedy) feels less like a lifeline to salvation and more like a reminder of a world rapidly receding from his grasp. The score by Bill Conti, famous for the soaring themes of Rocky (1976), here provides a grittier, more percussive pulse that underscores the tension rather than offering heroic uplift.

This wasn't a blockbuster – made for around $5 million, it pulled in roughly $9 million at the box office, respectable but not earth-shattering. Yet, its impact wasn't measured solely in dollars. It stood out as a raw, uncompromising look at youth incarceration, a stark contrast to more sanitized depictions. Does it hold up? Absolutely. The themes of systemic failure, the brutalizing effects of prison, and the desperate search for respect in hostile environments feel depressingly relevant.

Rating: 8/10

Bad Boys (1983) earns this score for its unflinching honesty, its claustrophobic atmosphere, and predominantly for Sean Penn's powerhouse central performance, a startlingly mature turn that burns itself into your memory. It's bolstered by strong support, particularly from Esai Morales in a terrifying debut. While undeniably bleak and violent, the film avoids exploitation, instead offering a potent, disturbing glimpse into a world many would prefer to ignore. It doesn't ask you to like its characters, only to witness their struggle.

What lingers most after the static hiss of the tape ends? For me, it’s the unsettling quiet after the violence, the chilling realization of what survival costs in a place like Rainford. It’s a tough watch, for sure, but a vital piece of 80s dramatic filmmaking that deserves its place on the shelf in VHS Heaven.