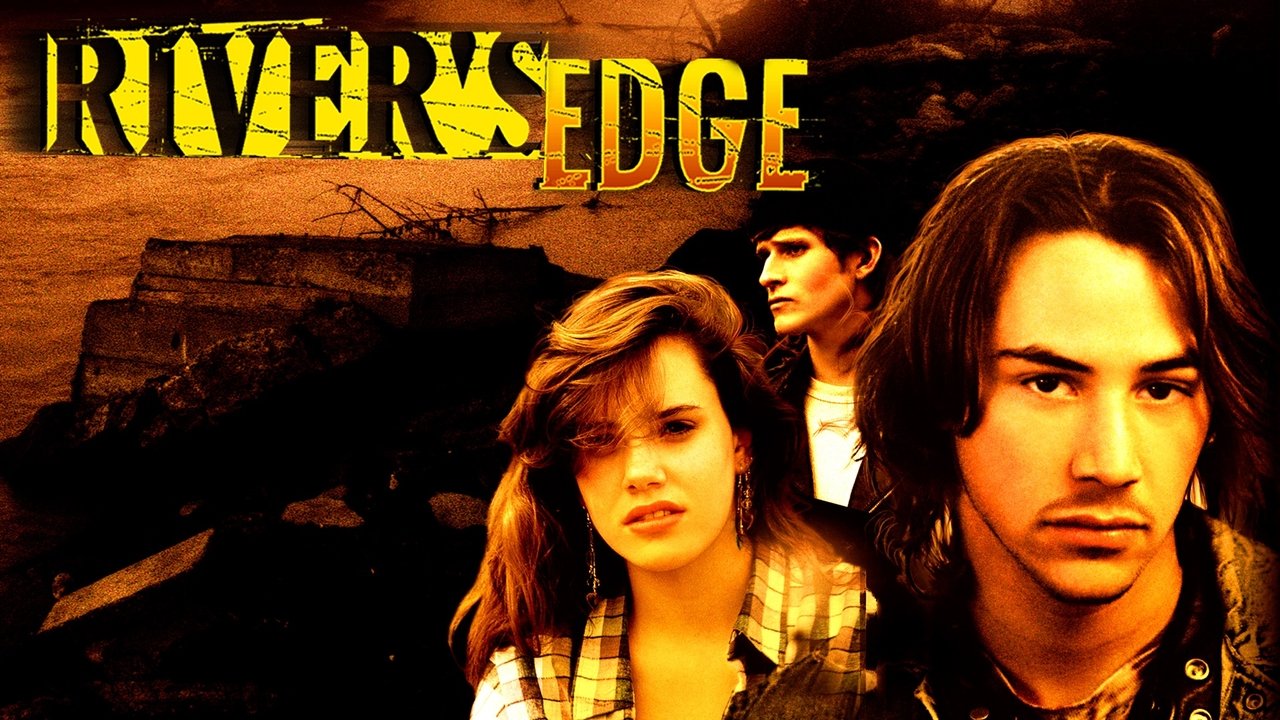

There's a particular kind of unease that certain films from the 80s managed to bottle, a disquiet that lingers long after the VCR whirred to a stop. It wasn't always about jump scares or overt gore; sometimes, it was the chilling reflection of something broken simmering just beneath the surface of everyday life. Tim Hunter's River's Edge (1986) is precisely that kind of film – a stark, uncomfortable, and utterly compelling look into a teenage wasteland where morality seems to have evaporated like morning mist off the titular river.

I remember renting this one, probably drawn by the familiar faces of Keanu Reeves and Crispin Glover on the cover, maybe expecting something closer to the usual teen angst dramas of the era. What unfolded instead was something far bleaker, a story that felt disturbingly plausible precisely because of its profound lack of melodrama. It forces us, even now, to confront a chilling question: what happens when empathy dies?

A Coldness by the Water

The setup is deceptively simple, yet horrifying in its banality. Samson 'John' Tollet (Daniel Roebuck, in a performance of unsettling vacancy) strangles his girlfriend Jamie. He doesn't run, he doesn't panic. He leaves her body by the riverbank and then, almost casually, tells his friends. This is where River's Edge pivots from a crime story into something far more unnerving. The film isn't primarily about the murder itself, but the ripple effect – or rather, the shocking lack of one – among John's circle of disaffected high school friends.

Led by the twitchy, speed-freak intensity of Layne (Crispin Glover), the group's initial reaction isn't horror or grief, but a disturbing mix of curiosity, apathy, and a bizarre, misguided sense of loyalty. They go to see the body. They debate what to do, not out of moral concern, but out of a self-preservation instinct warped by inertia and confusion. Hunter masterfully captures the drab, aimless atmosphere of their suburban Northern California town – the cheap beer, the heavy metal t-shirts, the rundown houses, the pervasive sense of going nowhere fast. It feels less like a setting and more like a character in itself, reflecting the internal emptiness of its young inhabitants.

Faces in the Wasteland

The performances are key to the film's enduring power. Crispin Glover delivers one of his most iconic and volatile performances as Layne. He’s a whirlwind of misplaced energy, frantic pronouncements, and a desperate need to be important, to impose order on a situation spiralling out of control, even if that "order" involves covering up a murder. His physicality – the jerky movements, the wide eyes – perfectly embodies the character's internal chaos. It’s a performance that teeters on the edge of caricature but remains terrifyingly believable within the film's world. Glover, who had recently broken through in Back to the Future (1985), showed an entirely different, darker side here.

Contrast Glover's mania with the quiet, simmering conscience provided by Matt, played by a young Keanu Reeves. Years before he asked "Woah!" in Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure (1989) or donned the trench coat for The Matrix (1999), Reeves demonstrates a remarkable stillness here. Matt is morally conflicted, disturbed by his friends' inaction but unsure how to break from the group's suffocating apathy. His scenes with Clarissa (Ione Skye, in her debut, radiating vulnerability) offer glimmers of humanity amidst the bleakness. Their tentative connection feels like the only potential anchor in a sea of indifference.

And then there's Feck, played with typically eccentric brilliance by the legendary Dennis Hopper. Hopper, already a counter-culture icon thanks to films like Easy Rider (1969), brings a burnt-out, menacing energy to the role of the paranoid, one-legged drug dealer living in seclusion with a blow-up doll named Ellie. Feck becomes an unlikely confidante and reflects a different kind of societal damage – an adult who has retreated entirely from a world he finds equally incomprehensible. His presence adds a layer of gothic strangeness, a ghost haunting the edges of this teenage tragedy.

Truth Stranger Than Fiction

What elevates River's Edge beyond mere provocative fiction is its grounding in reality. Neal Jimenez's sharp, unsparing script was inspired by the actual 1981 murder of Marcy Renee Conrad in Milpitas, California, where teenager Anthony Jacques Broussard killed her and subsequently showed off her body to numerous friends over several days before anyone finally reported it. Knowing this fact casts an even colder shadow over the film. The apathy isn't just a screenwriter's invention; it was horrifyingly real. Jimenez himself wrote the screenplay while recovering from a paralyzing hiking accident, pouring, perhaps, some of his own confrontation with harsh realities into the stark narrative. It's a detail that adds another layer of poignancy to the film's creation.

The production, helmed by the risk-taking Hemdale Film Corporation (who also gave us Platoon that same year), clearly wasn't afraid of the dark subject matter. Shot for a reported $1.9 million, the film feels raw and immediate, aided by Frederick Elmes's cinematography, which emphasizes the washed-out colours and bleak landscapes (Elmes, notably, would lens David Lynch's Blue Velvet also released in 1986, another film exploring darkness beneath suburbia). The soundtrack, featuring thrash metal bands like Slayer, further anchors the film in its time and place, amplifying the alienation and aggression simmering within the characters.

Why It Still Haunts

River's Edge isn't an easy watch. It doesn't offer simple answers or comforting resolutions. It presents a portrait of a generation adrift, desensitized perhaps by media, neglect, or simply a profound lack of guidance. It asks uncomfortable questions about peer pressure, moral responsibility, and the vacuum that forms when empathy fails. Does the film judge these kids? Not entirely. It observes them with a kind of horrified detachment, forcing us to consider the societal conditions that might breed such profound indifference. What stays with you isn't just the shocking central event, but the faces of those kids – Glover's frantic energy, Reeves' quiet turmoil, Skye's dawning horror, Roebuck's chilling blankness. It's a film that truly crawled under your skin back in the rental days, and its power hasn't diminished.

Rating: 9/10

This rating reflects the film's unflinching honesty, its powerful performances (especially from Glover and Reeves in defining early roles), and its chilling effectiveness in capturing a specific kind of youthful nihilism. It’s a vital, if deeply unsettling, piece of 80s cinema that dared to look into an abyss many preferred to ignore. River's Edge remains a stark reminder that sometimes the most terrifying monsters aren't supernatural, but tragically, recognizably human. It’s a film that doesn’t just entertain; it confronts.