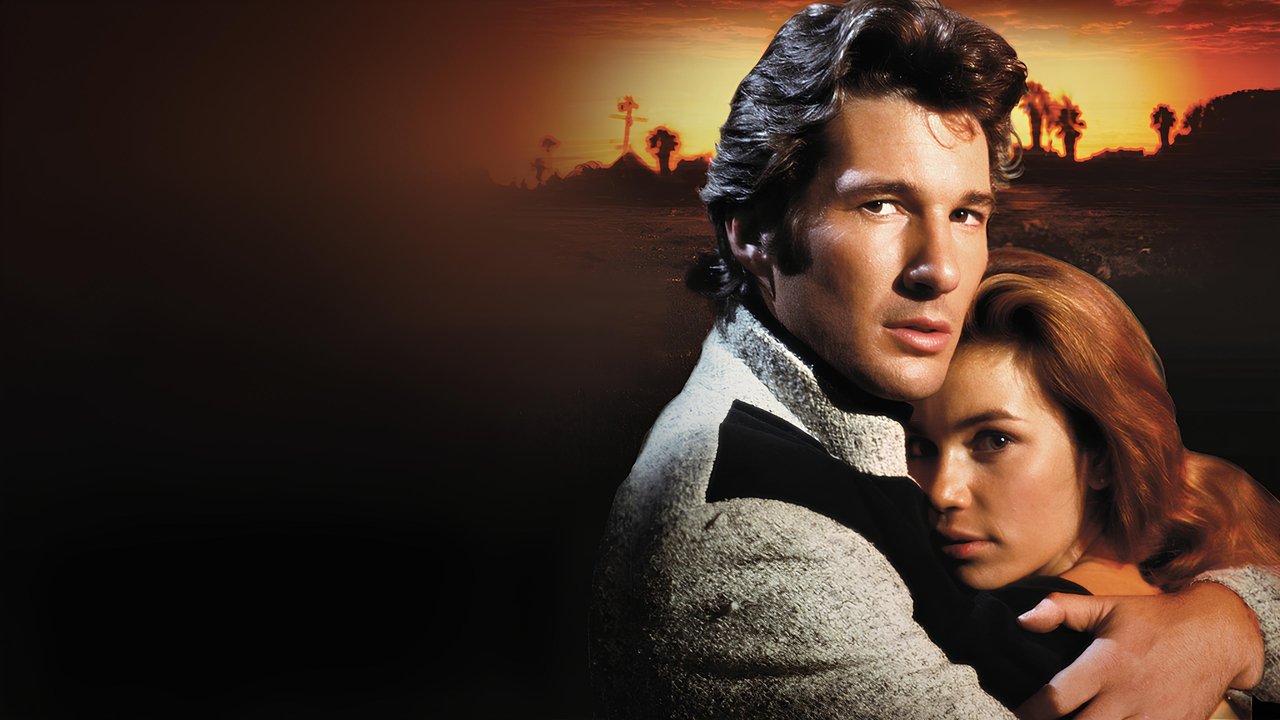

It starts not with a whisper, but with a stolen car and a desperate, almost feral energy. Watching Richard Gere ignite the screen as Jesse Lujack in Jim McBride's 1983 reimagining of Breathless, you're immediately confronted with the sheer audacity of the project. Remaking Jean-Luc Godard's seminal 1960 French New Wave classic, À bout de souffle, felt like artistic sacrilege to some back then. Yet, McBride and co-writer L.M. Kit Carson (a fascinating figure himself, who'd later pen Wim Wenders' Paris, Texas) didn't aim for mere imitation. Instead, they transplanted the story's core – impulsive criminal, elusive foreign girl, tragic trajectory – into a hyper-stylized, sun-drenched, rockabilly-fueled Los Angeles, creating something distinctly American and aggressively eighties.

Neon Noir and Rockabilly Recklessness

Forget the grainy Parisian streets of the original. This Breathless pulsates with the vibrant, sometimes sleazy, energy of early 80s LA. Shot largely on location, the film uses the city as a sprawling, colourful backdrop for Jesse's frantic movements. McBride, who clearly had an affinity for genre filmmaking (evident later in The Big Easy), drenches the screen in bold colours, often juxtaposing the bright California sun with the shadows Jesse can't outrun. It’s less cinéma vérité and more cinematic jukebox, powered by an absolutely killer soundtrack featuring everyone from Jerry Lee Lewis and Sam Cooke to punk pioneers X and The Stray Cats. This sonic landscape isn't just background noise; it's the frantic heartbeat of Jesse's existence, a constant rhythm driving him towards his inevitable fate.

Gere's Live Wire Act

At the film's volatile center is Richard Gere. Fresh off the cool detachment of American Gigolo (1980), here he's pure id, a tightly coiled spring of manic energy, misplaced charisma, and dangerous impulsivity. His Jesse Lujack isn't Jean-Paul Belmondo's effortlessly cool Michel Poiccard. Gere's version is more desperate, more overtly performative in his rebellion. He jives, he preens, he quotes Jerry Lee Lewis like scripture, and he harbors a peculiar obsession with the Silver Surfer comic book character – a fascinating detail reportedly stemming from Gere's own fixation at the time. It’s a performance that borders on caricature but remains utterly compelling because Gere commits so fully. He’s channeling Brando, Dean, and Elvis into a uniquely twitchy, self-destructive package. You can’t take your eyes off him, even when his actions are reprehensible. Does this intensity always translate into depth? Perhaps not entirely, but the raw physicality and unwavering commitment are undeniable.

Opposite him is the French actress Valérie Kaprisky as Monica Poiccard, the architecture student who becomes Jesse’s obsession and potential salvation. Kaprisky, relatively unknown to American audiences then, has the challenging task of embodying both fascination and fear. Monica is drawn to Jesse's dangerous allure, the sheer disruptive force he represents against her more structured life, yet she’s also acutely aware of the peril. Their relationship feels less like the intellectual sparring of the original and more like a primal push-and-pull, underscored by a raw sexuality that certainly pushed the boundaries of mainstream American cinema in 1983, earning the film its R rating and generating considerable buzz. Was the chemistry electric? It’s debatable – sometimes it feels more like bewilderment meeting obsession – but Kaprisky brings a necessary vulnerability and contemplative quality that contrasts sharply with Gere's explosive energy.

Style Over Substance?

This is the criticism most often levelled at McBride's Breathless, especially when measured against Godard's revolutionary original. And it's not entirely unfounded. Where Godard deconstructed cinematic language, McBride seems more interested in celebrating American pop culture iconography – fast cars, rock and roll, comic books, the allure of the outlaw. The philosophical underpinnings feel lighter, the existential dread replaced by a more straightforward sense of doomed romance and reckless abandon.

Yet, dismissing it solely as style over substance feels too easy. The film’s visual language is its substance, in many ways. The deliberate artificiality, the vibrant aesthetic, the pulsating soundtrack – these aren't just window dressing; they reflect Jesse's constructed persona and the superficiality of the world he's navigating (and rebelling against). It’s a film that feels like the 80s, capturing that decade's blend of surface gloss and underlying anxiety. It cost around $8 million to make and pulled in nearly $20 million at the box office (roughly $24.5M yielding $61M today), proving it found an audience despite mixed critical reception – Roger Ebert, for instance, championed its energy, while others found it a hollow echo.

A Cult Artifact Worth Revisiting

Watching Breathless today on a worn VHS tape (or, okay, maybe a streaming service that remembers the 80s) is a fascinating experience. It's undeniably a product of its time, from the fashion to the soundtrack to its particular brand of rebellious cool. Some elements might feel dated, the pacing occasionally uneven. I remember renting this from the local video store, probably lured in by Gere's star power and the promise of something edgy. It felt dangerous and exciting then, a splash of vibrant colour against the often more muted tones of early 80s cinema.

But beneath the surface style, there's a raw energy and a committed central performance that still resonates. It’s a film that dared to take a sacred text of cinema and remake it in its own brash, loud, distinctly American image. It doesn’t replace the original, nor should it try to. Instead, it stands as a fascinating, flawed, but often thrilling companion piece – a vibrant snapshot of a specific moment in film history.

Rating: 7/10

Justification: The score reflects the film's undeniable stylistic bravura, Richard Gere's electrifying and fully committed performance, and its killer soundtrack, which perfectly captures the intended mood. It stands as a bold piece of 80s filmmaking. However, it loses points for sometimes favouring style over narrative depth and for the inescapable (though perhaps unfair) comparison to the profound impact of its French New Wave predecessor. The chemistry between the leads isn't always convincing, either. Still, its energy and visual confidence make it a compelling watch.

Final Thought: More than just a remake, Breathless (1983) is a hyper-kinetic love letter to American rebellion, filtered through an unmistakable 80s lens – flawed, maybe, but pulsing with life and unforgettable energy.