From the Hopi language, it translates to "life out of balance," "crazy life," or "a state of life that calls for another way of living." Even before the first frame flickers onto the screen, Koyaanisqatsi (1983) announces itself as something utterly different. This wasn't your typical Friday night rental, nestled between the latest action hero flick and the teen comedies. Pulling this tape off the shelf felt like unearthing a strange artifact, a cinematic experience operating on a completely different frequency. And watching it? Well, that was something else entirely.

A World Painted in Motion and Time

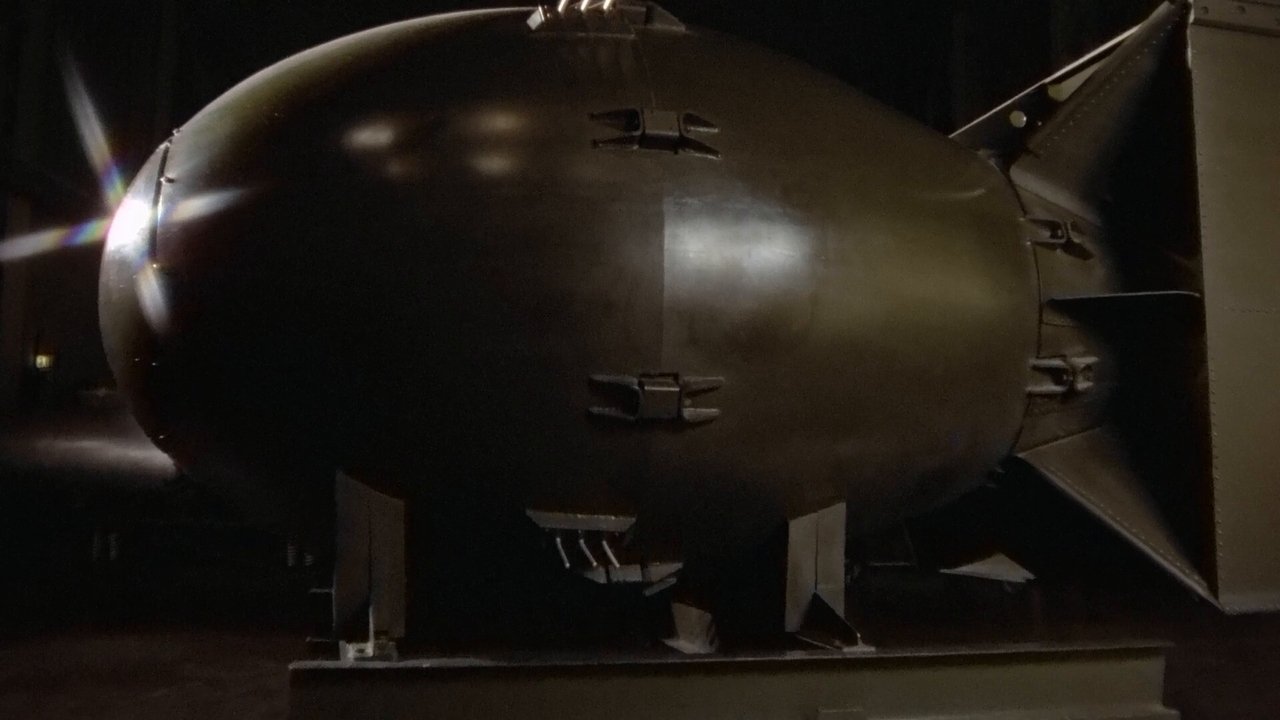

Forget plot, forget characters, forget dialogue. Director Godfrey Reggio crafts a mesmerizing, sometimes terrifying, visual poem using only images and music. The film opens with breathtaking shots of natural landscapes – canyons carved by time, clouds rolling like celestial oceans, water cascading in slow motion. There’s a majesty here, a sense of ancient rhythms. But then, the shift begins. We see mining operations scarring the earth, power lines stretching across vistas, and finally, the relentless pulse of the modern city.

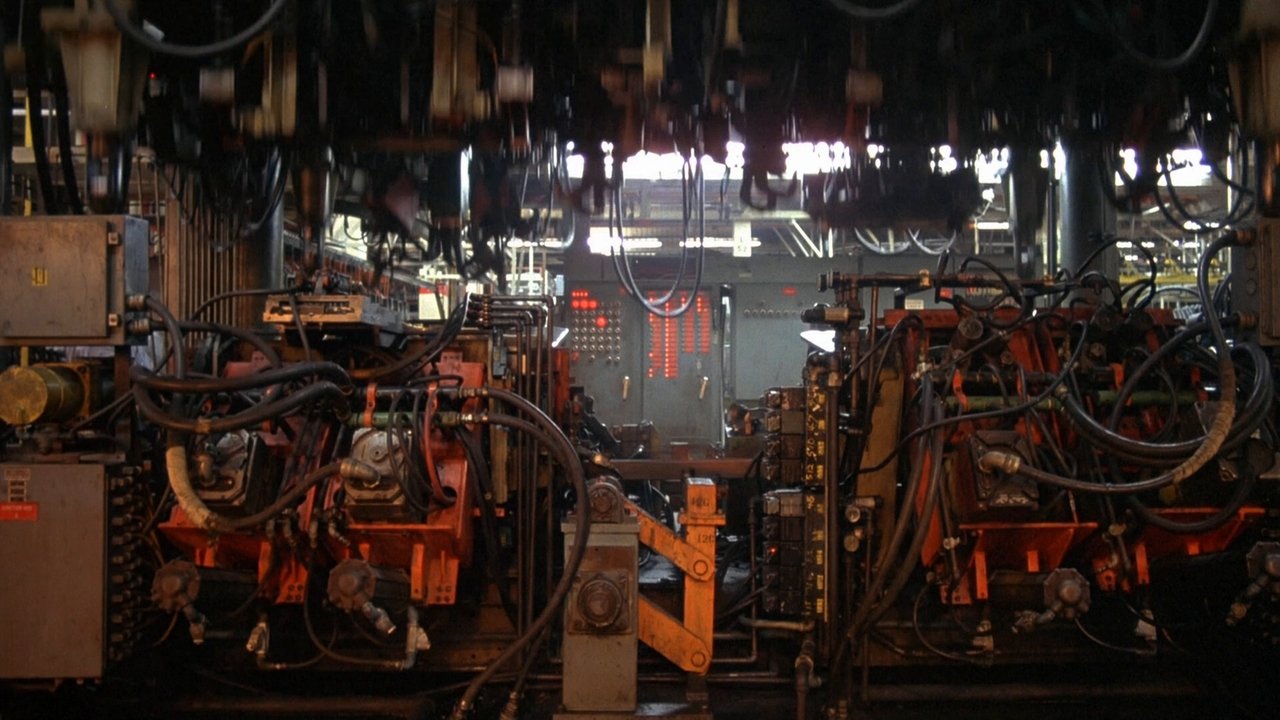

The film’s power lies heavily in the groundbreaking cinematography, largely the work of Ron Fricke (who would later bring us the similarly stunning Baraka (1992)). Koyaanisqatsi makes masterful use of both time-lapse and slow-motion photography. We see clouds skittering across the sky at impossible speeds, juxtaposed with the slow, almost mournful drift of people through urban landscapes. Cars become streaks of light, a frantic circulatory system of highways. Factories churn out identical products – Twinkies, famously – with hypnotic, dehumanizing repetition. The sheer scale and technical accomplishment, especially for the era, are staggering. One can only imagine the patience required; filming reportedly spanned nearly a decade, capturing footage across the United States.

The Haunting Pulse of Philip Glass

Equally crucial is the score by minimalist composer Philip Glass. This isn't background music; it's the film's voice, its heartbeat, its conscience. The repetitive, cyclical motifs build and release tension, sometimes creating a sense of exhilaration, other times evoking profound anxiety or sorrow. The music doesn't just accompany the images; it interprets them, deepens them, locks you into their rhythm. There’s a famous story that Glass and Reggio worked incredibly closely, with the music often being composed simultaneously with the editing process, creating an almost symbiotic relationship between sound and image. It’s hard to conceive of Koyaanisqatsi existing without this iconic score; it’s as integral as the visuals themselves.

Life Out of Balance: A Mirror to Ourselves

What is Koyaanisqatsi actually saying? That’s the question that lingers long after the VCR clicks off. It presents, rather than preaches. It shows us the beauty of the natural world and then contrasts it starkly with the frenetic, often overwhelming, pace and scale of modern technological life. Are we masters of our creations, or have they begun to master us? The sequences of people crammed onto escalators, moving like automatons, or the demolition of buildings in slow-motion clouds of dust – these images provoke thought without needing a single word of narration.

Watching it back then, on a grainy CRT screen, perhaps after adjusting the tracking dial on the VCR one too many times, the effect was still potent. It felt less like a movie and more like a transmission, a message beamed from somewhere outside the usual Hollywood channels. It was hypnotic, unsettling, and strangely beautiful all at once. It tapped into a nascent feeling, perhaps even an unconscious anxiety, about the speed at which the world was changing.

Behind the Experimental Curtain

Getting such an unconventional film made and seen was a challenge. It’s a fascinating piece of trivia that Francis Ford Coppola, riding high from Apocalypse Now (1979), lent his name as a presenter. His support was instrumental in securing distribution and bringing Koyaanisqatsi to a wider audience than it might otherwise have reached. The film’s budget, though difficult to pin down precisely due to the long production, was relatively modest for the scale of its imagery, a testament to the filmmakers' dedication and resourcefulness. Its initial reception was mixed – some critics hailed it as visionary, others found it pretentious or simplistic. But its cult status grew steadily throughout the VHS era, finding an audience appreciative of its unique sensory experience. It became that tape you’d show friends, prefacing it with, "You've gotta see this... it's... different."

The Echoes Remain

Koyaanisqatsi wasn't just a film; it was an event. It spawned two sequels, Powaqqatsi (1988) and Naqoyqatsi (2002), creating the "Qatsi trilogy," each exploring different facets of the relationship between humanity, nature, and technology. Its influence can be seen in countless music videos, commercials, and other films that adopted its time-lapse and slow-motion techniques to convey scale, speed, or alienation. It proved that cinema could communicate profound ideas and evoke powerful emotions without relying on traditional narrative structures.

Rating: 9/10

Koyaanisqatsi earns a high rating not because it's a conventional "entertaining" movie in the usual sense, but because it's a singular, audacious piece of filmmaking. Its technical mastery, the perfect marriage of image and Philip Glass's score, and its willingness to pose big questions without easy answers make it unforgettable. It’s a sensory immersion, a meditation, and a powerful critique rolled into one. Some might find its message heavy-handed or its pacing demanding, preventing a perfect score, but its impact and artistry are undeniable.

It remains a vital viewing experience, perhaps even more relevant today as our lives become ever more intertwined with technology and the pace seems only to accelerate. What does it mean to live a balanced life in such a world? Koyaanisqatsi doesn't tell you, but it surely makes you wonder.