It begins with a question, really. Not one spoken aloud, perhaps, but one that hangs heavy in the New York City air, thick as the summer heat clinging to the walls of a hotel room. What happens when colossal figures of an era – archetypes of intellect, beauty, power, and brute strength – collide in a space far too small for their mythic weight? This is the strange, potent cocktail served up by Nicolas Roeg in his 1985 film Insignificance, a movie that felt less like a rental and more like uncovering a coded message down at the local Video Palace back in the day.

### A Night of Icons and Anxieties

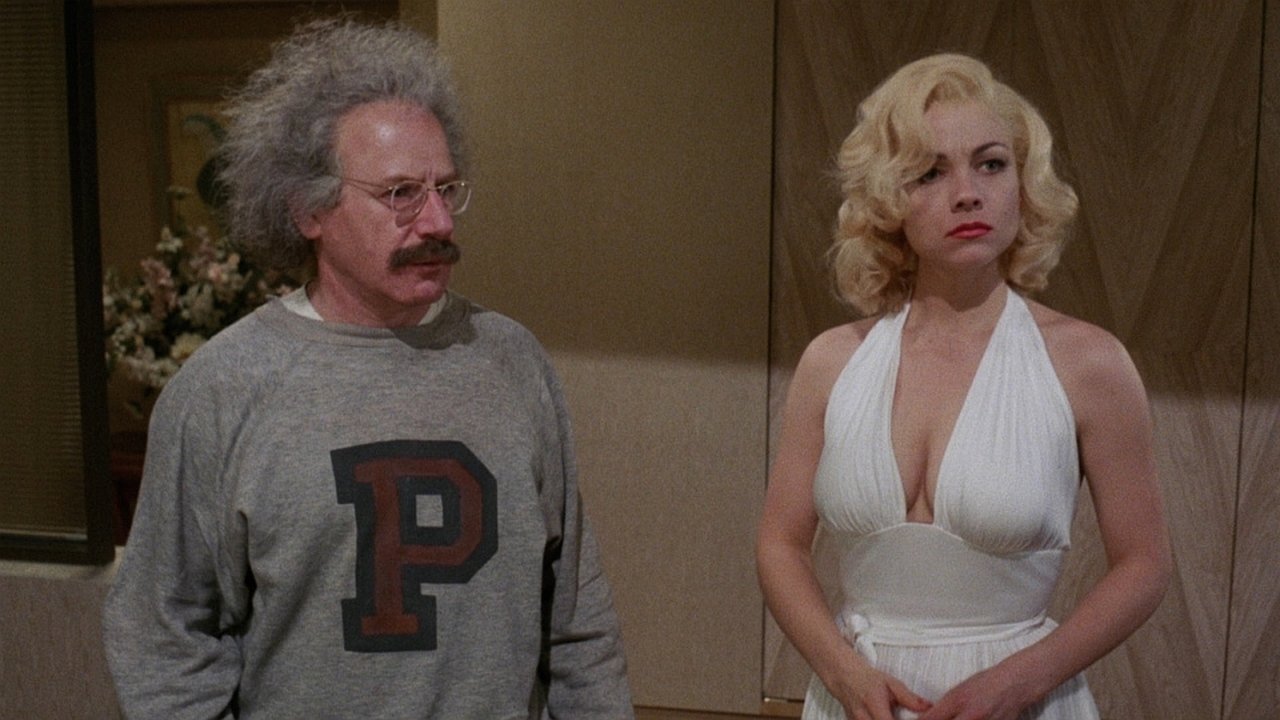

Based on Terry Johnson’s stage play, Insignificance imagines a single, sweltering night where four unnamed characters, clearly representing Albert Einstein (The Professor, played by Michael Emil), Marilyn Monroe (The Actress, Theresa Russell), Joe DiMaggio (The Ballplayer, Gary Busey), and Senator Joseph McCarthy (The Senator, Tony Curtis), converge in The Professor's hotel room. The premise itself is audacious, bordering on the surreal, but Roeg, never one for conventional narrative, treats it not as farce, but as a pressure cooker for the anxieties of the mid-20th century: the dawn of the atomic age, the corrosive nature of fame, the clash between intellect and brute force, and the terrifying power wielded by paranoia. It's less a story about these icons, and more a story using them as vessels for grand, often troubling ideas.

This wasn't your typical Friday night blockbuster rental. I remember seeing the VHS box, perhaps deceptively simple, hinting at something more cerebral than the usual fare. Roeg, the visionary director behind challenging masterpieces like Don't Look Now (1973) and The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), wasn't interested in straightforward biography. Instead, he employs his signature fragmented editing and non-linear approach, weaving together moments in the hotel room with jarring, symbolic flashes – a ticking watch, astronomical imagery, the devastating explosion of an atomic bomb over Hiroshima. These cuts aren't random; they're Roeg’s way of connecting the intimate struggles within the room to the vast, terrifying forces shaping the world outside. It’s a challenging style, demanding attention, forcing you to piece together the thematic puzzle.

### Embodied Ideas, Fractured Souls

The performances are crucial here, as the actors aren't aiming for strict impersonation but rather embodying the essence of these figures. Michael Emil portrays The Professor with a gentle, world-weary intelligence, burdened by the horrific potential unleashed by his own discoveries. There's a profound sadness in his eyes, a quiet desperation to connect on a human level amidst the swirling chaos.

Theresa Russell, who was Roeg's wife at the time and a frequent collaborator (memorably in Bad Timing from 1980), gives a remarkable performance as The Actress. She captures the breathy vulnerability and manufactured bombshell persona, but crucially reveals the sharp intellect and deep-seated insecurity beneath. The famous scene where she playfully, yet accurately, explains the Theory of Relativity to The Professor using toys and everyday objects is a standout, showcasing both the character's hidden depths and Russell's captivating screen presence. It’s a moment that perfectly encapsulates the film's central theme: the vast gulf between public perception and private reality.

Then there's Tony Curtis, virtually unrecognizable from his charming matinee idol days, who sinks his teeth into the role of The Senator. He embodies the invasive, self-important bluster of McCarthyism, a paranoid force seeking enemies under every bed, even intruding upon the sanctity of The Professor’s refuge. Curtis delivers a performance simmering with barely concealed menace. And Gary Busey, as The Ballplayer, brings a palpable sense of frustration and wounded pride, a man defined by physical prowess struggling to comprehend the complexities swirling around his estranged wife, The Actress.

### Echoes in a Confined Space

Shooting largely within the confines of the hotel room set could have felt stagey, but Roeg uses the limitation to amplify the claustrophobia and intensity. The room becomes a microcosm of the world, a stage where historical forces and personal dramas play out in excruciating close-up. One fascinating bit of trivia: the film was shot at Lee International Studios in Wembley, London, convincingly recreating a mid-50s New York hotel. Despite its challenging, intellectual nature, Insignificance clearly struck a chord with critics, earning a nomination for the Palme d'Or at the 1985 Cannes Film Festival and winning the Technical Grand Prize for its innovative techniques. It wasn't a box office smash – its $1.5 million budget likely wasn't recouped domestically – but its arthouse success cemented its cult status.

What lingers long after the tape finishes whirring is the film’s central, melancholic question about significance itself. In a universe governed by immense, impersonal forces, symbolized by both relativity and the atomic bomb, what meaning can individual lives hold, especially those lived under the intense glare of the public eye? Are these iconic figures merely fleeting moments, their fame and influence ultimately… insignificant? Roeg offers no easy answers, leaving the viewer adrift in the same sea of existential doubt that permeates the film.

It’s not a comfortable watch, nor is it meant to be. Insignificance demands engagement, rewards contemplation, and occasionally frustrates with its elliptical nature. But for those willing to dive into its strange, symbolic depths, it offers a uniquely potent reflection on a pivotal moment in history and the fragile human beings caught within its gears. Finding this on VHS felt like discovering a challenging piece of art hidden amongst the escapism, a reminder that sometimes the most profound stories are whispered in the quiet spaces between explosions.

Rating: 8/10 - This score reflects the film's audacious concept, Nicolas Roeg's masterful (if challenging) direction, and the compelling performances that bring its symbolic archetypes to life. It’s a dense, thought-provoking piece of 80s arthouse cinema that uses iconic figures to explore deep anxieties about fame, knowledge, and humanity's place in a newly nuclear world. It loses a couple of points simply because its deliberately fragmented style and intellectual demands won't resonate with everyone, but its ambition and lingering questions make it a truly significant cinematic experience.

Insignificance remains a fascinating anomaly from the VHS era – a film that dared to be difficult, asking questions that echo long after the credits roll. What, ultimately, defines our time here?