There are films that entertain, films that comfort, and then there are films like Bad Boy Bubby – films that crawl under your skin and stay there, demanding you reckon with what you’ve just witnessed. Released in 1993, this Australian oddity wasn't just another tape on the rental shelf; it felt more like contraband, whispered about, passed between those brave enough to venture into its deeply unsettling, yet strangely compelling, world. It’s a viewing experience that doesn't fade easily, lingering long after the VCR clicked off.

A World Confined

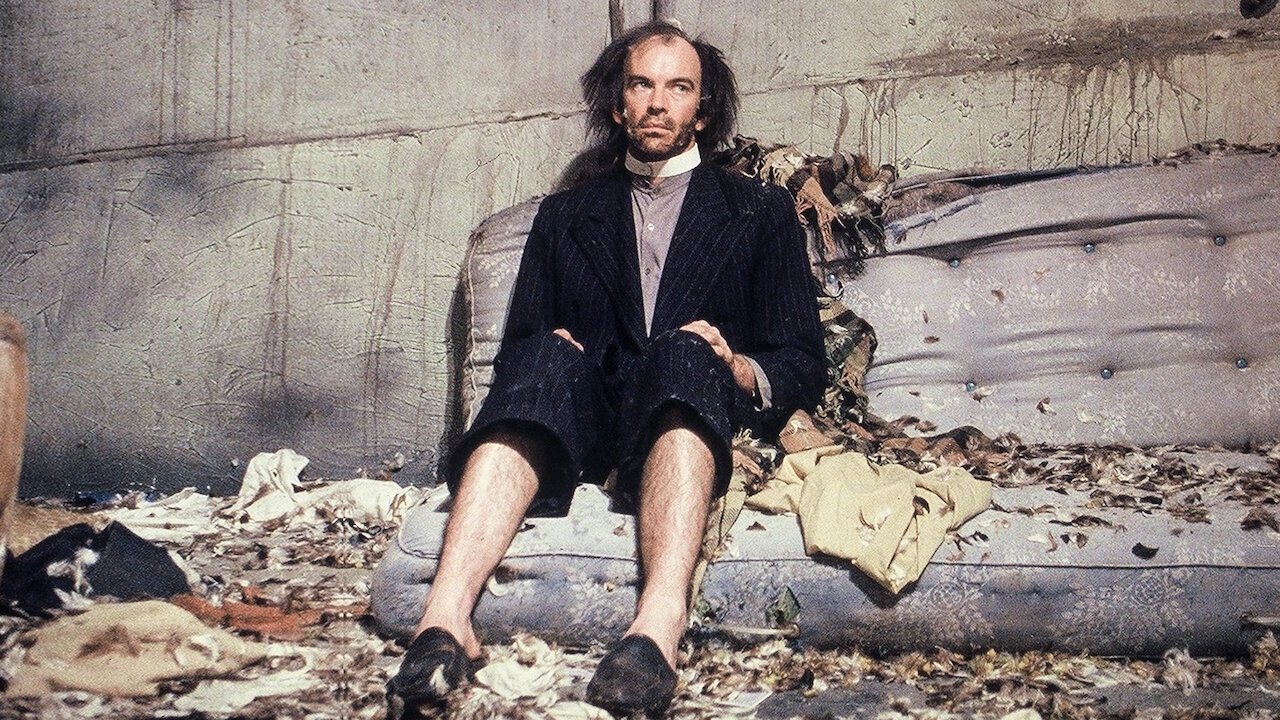

The film opens with perhaps one of the most disturbing and claustrophobic scenarios imaginable. Bubby (Nicholas Hope) is a 35-year-old man who has never left the squalid two-room apartment he shares with his abusive mother, Flo (Claire Benito). His reality is entirely shaped by her twisted teachings: the outside air is poison, God looks like her, and sex is a violent, controlling act. It's a suffocating existence, depicted with unflinching grime and despair. You feel the stale air, the oppressive closeness, the sheer horror of Bubby's manufactured world. Director Rolf de Heer, who also penned the screenplay, plunges us headfirst into this nightmare, forcing us to confront the terrifying potential of absolute isolation and manipulation.

An Astonishing Central Performance

What elevates Bad Boy Bubby from mere provocation to something genuinely profound is the astonishing, fearless performance by Nicholas Hope. His portrayal of Bubby is a masterclass in transformation. Initially, Bubby is almost a blank slate, his primary mode of communication being mimicry – repeating phrases and sounds he hears, often inappropriately and to shocking effect. Hope embodies this arrested development with unsettling conviction, capturing both the childlike innocence warped by abuse and the simmering potential for something more. As Bubby eventually breaks free from his confinement, Hope charts his painful, confusing, and sometimes darkly funny journey of discovery. It's a performance devoid of vanity, utterly raw and physically demanding. Rumour has it Hope stayed deep in character during the shoot, a commitment that absolutely translates to the screen – you don't just watch Bubby, you experience the world through his fractured lens.

Seeing Through Thirty-Two Eyes

Bubby's emergence into the outside world is where Rolf de Heer deploys his most audacious technical gamble. To reflect Bubby's constantly shifting, unformed perception of reality, the film utilizes thirty-two different cinematographers after he leaves the apartment. Each new encounter, each new environment, potentially brings a subtle (or sometimes jarring) shift in visual style. It’s a brilliant conceit, mirroring Bubby’s sensory overload and his struggle to make sense of a world he was taught didn't truly exist. This wasn't just a gimmick; it was a deliberate, risky choice that pays off immensely, making the viewer feel as disoriented and overwhelmed as Bubby himself.

Adding to this immersive, subjective experience is the pioneering use of binaural sound recording. De Heer placed microphones directly in Nicholas Hope's wig, near his ears, capturing audio much like Bubby would perceive it. This is why the film often came with a recommendation – practically a necessity – to be watched with headphones. Doing so transforms the viewing; the world swirls around you, conversations feel intensely intimate or chaotically distant, amplifying the feeling of being inside Bubby's head. It’s a technical detail that highlights the level of thought invested in creating a truly unique cinematic perspective, something especially remarkable for a film reportedly made for around $800,000 AUD.

Confronting the Uncomfortable

Let's be clear: Bad Boy Bubby is not an easy film. It confronts themes of incest, animal cruelty (the infamous cat scene remains deeply controversial, though arguably serves a narrative purpose in Bubby's understanding of consequence), violence, and exploitation head-on. It forces uncomfortable questions about nature versus nurture, the corrupting influence of society, and the very definition of normalcy. Bubby’s journey takes him through encounters with a Salvation Army band, a stint in prison, time with people with disabilities, and even unlikely fame as the frontman of a noise-rock band spouting his mother's hateful rhetoric mixed with his own naive observations. Does his eventual, bizarre integration into society redeem him, or indict us? The film offers no simple answers, leaving the viewer to grapple with the implications. It's a testament to its power that, decades later, these questions still resonate.

Legacy of a Cult Shock

Upon release, Bad Boy Bubby polarized audiences and critics. It won the prestigious Special Jury Prize at the Venice Film Festival but was also banned or heavily censored in several places. Its reputation spread through word-of-mouth, fueled by those worn VHS copies that likely circulated among adventurous cinephiles. It became that film – the one you dared your friends to watch, the one that guaranteed a reaction. Despite, or perhaps because of, its confrontational nature, it cemented its place as a true cult classic of 90s Australian cinema, a singular vision from Rolf de Heer (who would continue to make challenging films like The Tracker (2002) and Charlie's Country (2013)) and launched Nicholas Hope into the cult film stratosphere.

Rating: 9/10

The score reflects the film's undeniable power, its audacious technical innovation, and the sheer force of Nicholas Hope's central performance. It's a near-masterpiece of challenging cinema, held back only slightly by moments where its confrontational nature might feel excessive to some. However, its commitment to its singular vision and its lasting impact are undeniable. Bad Boy Bubby isn't just watched; it's experienced, endured, and ultimately, impossible to forget.

It leaves you pondering the thin veil between innocence and corruption, questioning the 'civilising' forces of society, and wondering just how much of Bubby's fractured worldview might, unsettlingly, reflect our own.