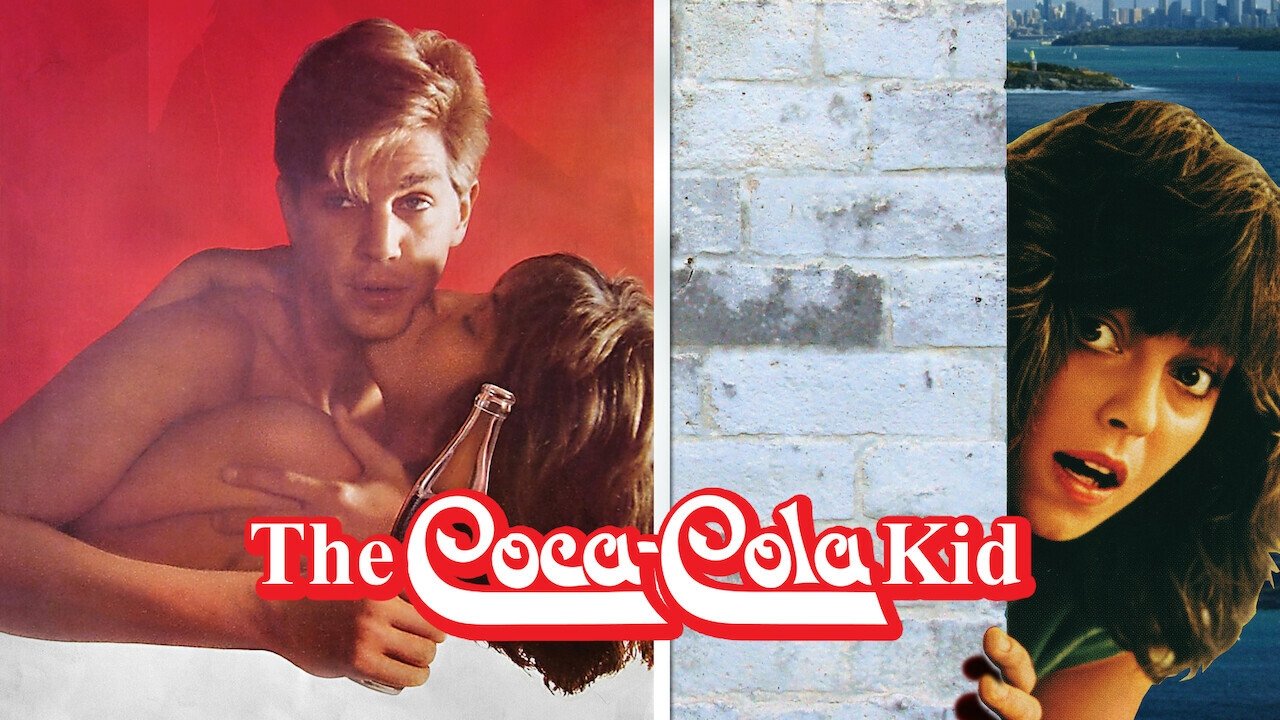

It's a curious thing, isn't it, when a filmmaker known for provocative, politically charged, and often surreal European cinema turns their lens towards... fizzy drinks in the Australian outback? That unexpected pivot is precisely what makes Dušan Makavejev's The Coca-Cola Kid (1985) such a fascinating entry in the annals of 80s filmmaking. Makavejev, the mind behind challenging works like WR: Mysteries of the Organism (1971), tackling a story seemingly about corporate expansion feels almost like a prank, yet the result is a film brimming with quirky charm, simmering tensions, and a surprisingly gentle examination of cultural collision. It's the kind of film that might have caught your eye on the rental shelf precisely because it seemed so... odd.

Corporate Zeal Meets Outback Charm

The premise itself hums with an inherent absurdity that Makavejev leans into. Eric Roberts, radiating an almost unnerving intensity, plays Becker, a hotshot marketing executive dispatched from Atlanta to Coca-Cola's Australian division. Becker is pure 80s corporate archetype: driven, immaculately dressed (at first), and utterly convinced of Coke's manifest destiny to conquer every corner of the globe. His discovery of a "Coca-Cola desert" – the remote Anderson Valley, stubbornly loyal to its own local soft drink crafted by the eccentric T. George McDowell (Bill Kerr) – becomes his obsession, his personal Everest. The ensuing battle of wills is less boardroom strategy and more a slow, sun-drenched surrender to a different way of life.

Roberts, fresh off acclaimed performances in films like Star 80 (1983), channels his trademark volatility into Becker's unwavering focus. It’s a performance that initially feels jarringly rigid against the laid-back Australian backdrop, but that’s precisely the point. He is the alien here, the tightly wound mechanism in a land that operates on a different rhythm. Watching Becker gradually unravel, or perhaps re-ravel into something more human, under the valley's heat and the influence of his captivatingly unconventional secretary Terri (Greta Scacchi), forms the film's emotional core.

An Unlikely Blend of Styles

Scacchi, who had recently captivated audiences in Heat and Dust (1983), provides the perfect counterpoint to Roberts' manic energy. Her Terri is intelligent, independent, and possesses a quiet allure that feels deeply rooted in the landscape. She's amused by Becker, attracted to him, but never intimidated. Their chemistry is unconventional, sparking with flickers of genuine connection amidst the culture clash. And Bill Kerr as T. George McDowell? He’s magnificent – the embodiment of laconic, stubborn Australian spirit, utterly unfazed by the corporate giant knocking at his door. His folksy wisdom and unwavering commitment to his own fizzy creation provide much of the film's gentle humour and thematic weight.

Makavejev’s direction is key here. He doesn’t sand off his European arthouse edges entirely. There are moments of visual wit, slightly off-kilter framing, and an observational style that finds poetry in the mundane – the dusty streets, the unique local characters, the vastness of the landscape itself. He lets the inherent strangeness of the situation breathe, resisting the urge to flatten it into a conventional fish-out-of-water comedy. The score, featuring contributions from Tim Finn (of Split Enz fame) and even some synth-pop moments perfectly anchoring it in the mid-80s, adds another layer to its unique texture.

Retro Fun Facts: Beyond the Fizz

The journey of The Coca-Cola Kid to the screen is almost as quirky as the film itself. Based on short stories from Australian author Frank Moorhouse's book "The Americans, Baby," the script retains that episodic, character-focused feel. Interestingly, the Coca-Cola company initially cooperated with the production, perhaps envisioning a feature-length advertisement. However, they reportedly weren't thrilled with the final film, particularly its ambiguous ending and Makavejev's less-than-jingoistic portrayal of corporate power. It certainly wasn’t the glossy celebration they might have anticipated! Filmed largely in Sydney and the beautiful Blue Mountains region of New South Wales, the movie captures an authentic sense of place, far removed from stereotypical postcard images of Australia. While not a box office smash (earning back its modest estimated $3 million budget but little more), its unique flavour helped it find a dedicated audience on VHS, becoming one of those delightful discoveries for discerning renters. Roberts himself allegedly dove deep into character research, studying the mannerisms and mindset of real Coca-Cola executives to perfect Becker's driven persona.

A Lingering, Unique Aftertaste

What lingers after watching The Coca-Cola Kid isn't necessarily a craving for soda, but a warm appreciation for its gentle eccentricities. It’s a film that explores big themes – globalization, cultural identity, the tension between progress and tradition – but does so with a light touch and a generous spirit. It doesn’t offer easy answers. Does Becker truly change, or just adapt his tactics? Does Anderson Valley inevitably succumb to the global tide? Makavejev leaves these questions hanging, preferring to focus on the human connections forged in this unusual crucible. It captures a specific mid-80s moment, yet its core concerns about local character versus homogenizing forces feel surprisingly relevant today. Does the sheer strangeness of a maverick Yugoslav director helming this project, backed (initially) by a global mega-corporation, add another layer of delightful irony? Absolutely.

Rating: 7/10

This rating reflects the film's undeniable charm, strong central performances, and unique directorial vision. It's occasionally uneven, and its deliberate pacing might test some viewers accustomed to faster fare, but its originality and gentle soul shine through. It doesn't quite reach the heights of Makavejev's more audacious work, nor is it a laugh-a-minute comedy, but it succeeds beautifully on its own quirky terms.

The Coca-Cola Kid remains a delightful oddity, a sun-drenched fable about finding humanity in the most unexpected of corporate assignments. It’s a reminder that sometimes the most refreshing discoveries aren't found in a bottle, but in the character of a place and its people.