It’s a peculiar kind of vulnerability, isn't it? That moment you realize the signposts of youth – the parties, the carefree choices, the endless possibilities – are receding in the rearview mirror, replaced by mortgage payments, career anxieties, and the daunting prospect of bringing another human into the world. This quiet dread, this bittersweet transition, lies at the heart of John Hughes' often overlooked 1988 film, She's Having a Baby. Coming from the maestro of teenage angst who gave us indelible high school portraits like The Breakfast Club (1985) and Ferris Bueller's Day Off (1986), this felt like Hughes himself was graduating, wrestling with the complexities that follow prom night.

Growing Pains, Grown-Up Edition

Forget the lockers and the lunchroom politics; She's Having a Baby trades them for the manicured lawns and simmering anxieties of suburbia. The film follows Jefferson "Jake" Briggs (Kevin Bacon) and his wife Kristy (Elizabeth McGovern) from their wedding day through the trials of early marriage and into the titular event. It's a path many tread, yet Hughes, ever the astute observer of internal landscapes, focuses less on the external milestones and more on Jake's churning psyche. This isn't the cocky rebellion of Ferris Bueller; it's the quieter, more pervasive fear of losing oneself to conformity, of dreams deferred settling into a comfortable, yet perhaps unfulfilling, reality. Hughes himself drew heavily on his own early marriage experiences for the script, lending Jake’s anxieties an air of uncomfortable truth. You get the sense this was a deeply personal project for him, a departure he needed to make.

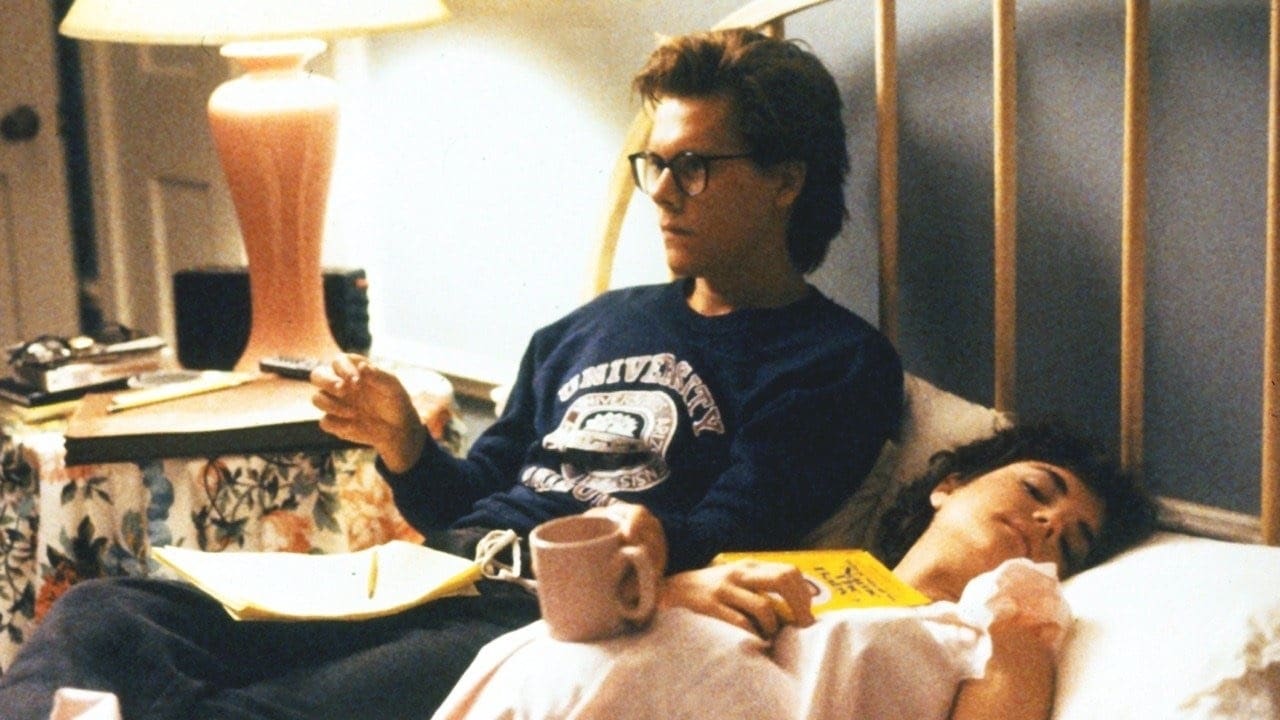

Bacon's Burden

Kevin Bacon, then firmly establishing himself beyond his Footloose (1984) fame, delivers a performance steeped in relatable neurosis. He perfectly embodies the young husband caught between genuine love for his wife and the nagging feeling that life is passing him by. His Jake is charming but deeply insecure, prone to elaborate fantasy sequences that visualize his fears and desires – imagining himself as a conquering hero, a tortured artist, or simply escaping the perceived trap of domesticity. These sequences, while sometimes stylistically jarring against the film's otherwise grounded reality, are crucial. They're Jake's internal monologue made manifest, showing us the gap between the life he has and the ones he thinks he's missing out on. Bacon makes Jake’s struggle feel authentic; even when he’s being selfish or immature, there's a vulnerability there that keeps you invested. You might not always like Jake, but chances are, especially if you navigated similar life stages in that era, you understood him.

Ground Control to Major Tom(cat)

Providing the essential anchor to Jake's flights of fancy is Elizabeth McGovern as Kristy. It’s a role that could easily have become a thankless "supportive wife" cliché, but McGovern imbues Kristy with warmth, intelligence, and a quiet strength that often highlights Jake's self-absorption. She's not naive to his anxieties, but she possesses a maturity he lacks. Their relationship feels lived-in, capturing the mixture of affection, frustration, and deep-seated connection that defines many young marriages. Adding fuel to Jake's existential fire is his best friend, Davis McDonald, played with slick, predatory charm by a young Alec Baldwin. Davis represents everything Jake fears he's losing: freedom, financial success, bachelor swagger. He's the devil on Jake's shoulder, whispering temptations of infidelity and escape, a stark contrast to the life Jake is building, however imperfectly.

Hughes Behind the Camera: A Shift in Tone

Hughes brings his signature observational humor and knack for dialogue to the proceedings, but the overall tone is more melancholic, more contemplative than his teen fare. The film wrestles with genuine emotional weight, particularly in its final act as complications arise during childbirth. This shift wasn't universally embraced at the time; the film was a commercial disappointment, grossing around $16 million against a $20 million budget. Perhaps audiences expecting another feel-good Hughes romp weren't prepared for this more introspective, sometimes uncomfortable look at adulthood. Yet, looking back, it feels like a necessary step in his evolution as a filmmaker. It’s fascinating to see Hughes utilize the familiar backdrop of suburban Illinois (much of it filmed in Winnetka, like his earlier hits) to explore distinctly adult fears. And who could forget that end credits sequence? The rapid-fire baby name suggestions from a parade of stars – Matthew Broderick, Bill Murray, Dan Aykroyd, John Candy, Magic Johnson, and many more – feels like a quintessential Hughes touch, a communal, slightly chaotic blessing on the new parents, and maybe a wink to his own circle of collaborators.

Echoes in the Rearview

Watching She's Having a Baby today, possibly on a worn-out VHS tape pulled from the back of a shelf, feels like revisiting an old friend who’s grown up alongside you. The anxieties about commitment, career pressures, and the seismic shift of parenthood remain remarkably resonant. The specific 80s aesthetics – the fashion, the decor – might trigger a nostalgic smile, but the core emotional journey feels timeless. I distinctly remember renting this back in the day, perhaps expecting something lighter, and being surprised by its quiet depth and the questions it lingered on long after the VCR clicked off. It doesn't offer easy answers, but it captures a specific, often confusing, chapter of life with sincerity.

Rating: 7/10

This score reflects the film's genuine heart, Kevin Bacon's and Elizabeth McGovern's truthful performances, and John Hughes' brave step into more mature territory. It captures the anxieties of a generation grappling with adulthood with sensitivity and insight. Points are deducted for a sometimes uneven tone and fantasy sequences that don't always seamlessly integrate, plus a narrative perspective heavily tilted towards the male experience. However, its core emotional honesty resonates strongly.

She's Having a Baby may not be the Hughes film most readily quoted or celebrated, but it possesses a quiet staying power. It’s a thoughtful, sometimes bittersweet look at the moment life demands you trade youthful dreams for grown-up realities, leaving you to wonder: was the trade worth it?