The hum of the VCR used to feel like a prelude, didn't it? A mechanical whirring that promised escape, maybe excitement, sometimes pure, unadulterated dread. With William Friedkin's To Live and Die in L.A. (1985), that hum often felt like the charge building before a lightning strike. This wasn't just another cop movie slid into the player; it was 90 minutes of sun-bleached concrete, moral decay, and reckless velocity that left you feeling wired, maybe even a little dirty, long after the tape clicked off.

Sun, Sweat, and Secret Service

Forget the postcard version of Los Angeles. Friedkin, already a master of urban grit with The French Connection (1971), paints an L.A. that’s all shimmering heat haze, industrial sprawl, and the kind of desperation that clings to the air like smog. We’re thrown headfirst into the world of Richard Chance (William Petersen), a Secret Service agent whose definition of 'reckless' makes most action heroes look like they’re playing by the library rules. When his veteran partner is gunned down days before retirement, Chance’s pursuit of the elusive, high-end counterfeiter Rick Masters (Willem Dafoe) spirals from investigation into outright obsession. It’s a setup we’ve seen before, but rarely executed with such nihilistic fury.

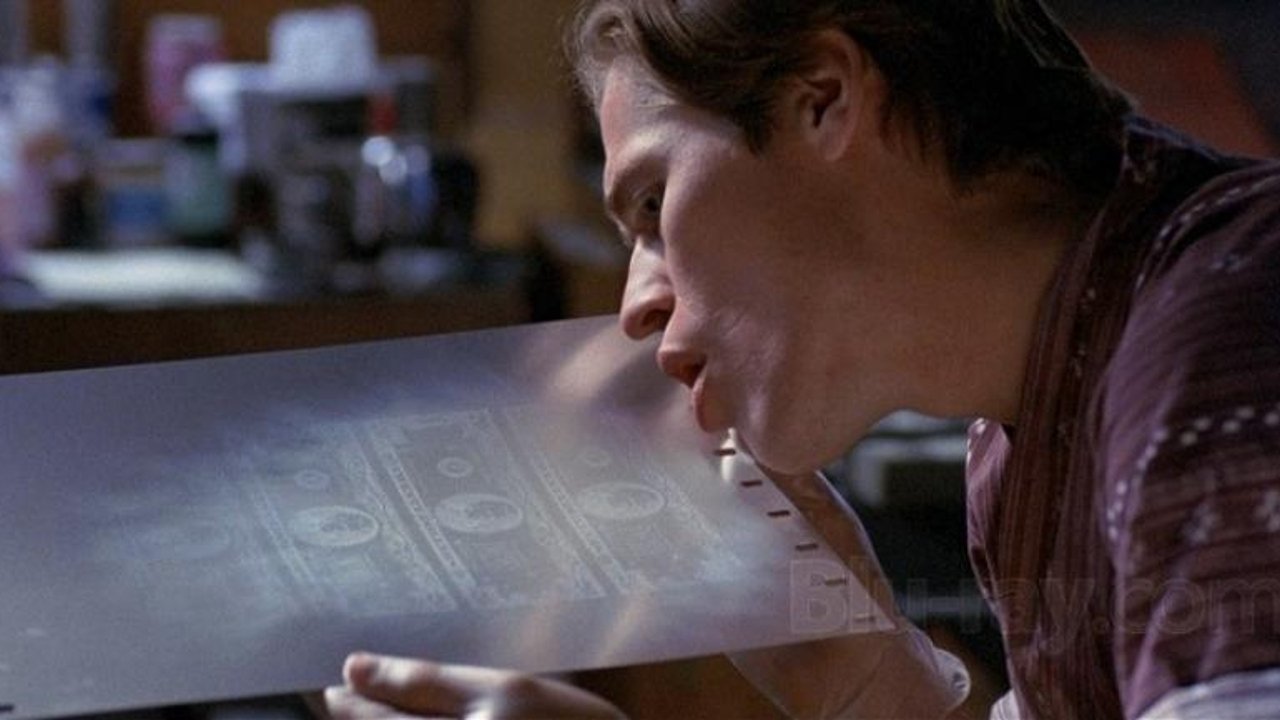

The Art of the Counterfeit

What elevates To Live and Die in L.A. immediately is its villain. Masters isn't some cackling maniac; he’s an artist, a craftsman whose medium happens to be fake currency. Willem Dafoe, in one of his most magnetic early roles, portrays him with an unnerving calm, a chilling focus that makes his bursts of violence all the more shocking. There's a famous sequence detailing Masters' counterfeiting process – the inks, the plates, the meticulous burning of flawed bills – set to Wang Chung's pulsing synth score. It's hypnotic, almost seductive, blurring the lines between crime and creation. It’s said that Dafoe actually learned some real counterfeiting techniques for the role, adding a layer of unnerving authenticity to his portrayal. You watch him work, and for a moment, the illegality almost fades behind the sheer skill on display. Doesn't that meticulous detail somehow make him even more menacing?

Friedkin Unleashed

William Friedkin directs with a relentless, almost feral energy. He plunges you into the action, favoring raw immediacy over polished choreography. The film famously features one of the most harrowing and realistic car chases ever committed to celluloid – a terrifying sequence involving speeding the wrong way down a freeway that feels utterly chaotic and genuinely dangerous. Forget CGI smoothness; this is pure metal-on-metal terror. Friedkin, known for pushing boundaries (and sometimes his crew), reportedly didn't secure official permits for parts of this chase, adding another layer of real-world risk to the on-screen mayhem. William Petersen, embodying Chance’s adrenaline-junkie persona, performed many of his own stunts, including the bungee jump off the bridge early in the film, further cementing the film's raw, visceral feel. The whole production crackled with this high-wire energy, fueled by a modest $6 million budget that demanded grit over gloss.

No Heroes Here

This is where To Live and Die in L.A. really dug under your skin back in the day, and perhaps still does. Chance isn't a hero. He's impulsive, ethically compromised, and arguably just as dangerous as the man he's hunting. Petersen, years before becoming the methodical Gil Grissom in CSI, is electrifyingly volatile here. He bends rules, breaks laws, and drags his increasingly uneasy partner, John Vukovich (John Pankow, providing a necessary moral counterweight), deeper into the abyss. The film, based on the novel by former Secret Service agent Gerald Petievich, offers no easy answers or comfortable archetypes. It presents a world where the lines aren't just blurred; they're practically erased by the scorching California sun and the heat of obsession. I remember renting this as a teenager, expecting maybe Lethal Weapon with fake money, and being utterly floored by its bleakness and cynicism. Did that twist ending genuinely shock you back then? It felt like a punch to the gut.

The Pulse of the 80s

Beyond the grit and grime, the film looks and sounds undeniably 80s, but in a way that feels integral, not just dated. The synth-heavy score by Wang Chung isn't just background noise; it's the nervous system of the film, throbbing with electronic anxiety and driving the relentless pace. The fashion, the cars, the neon glow filtering through Venetian blinds – it all contributes to a specific time and place, a portrait of excess and danger simmering beneath a veneer of cool.

Lasting Impact

To Live and Die in L.A. wasn't a runaway blockbuster ($17.3 million at the box office wasn't exactly setting the world on fire), but its influence seeped into the genre. It was a darker, more cynical beast than many of its contemporaries, پیشبینی کننده the morally grey anti-heroes that would become more common later. It remains a testament to Friedkin's uncompromising vision and features career-defining (or certainly career-igniting) performances from Petersen and Dafoe. It’s a film that doesn’t coddle you; it grabs you by the collar and shoves you face-first into the L.A. underworld.

---

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's masterful direction, its raw intensity, the unforgettable performances (especially Dafoe's chilling antagonist), and one of the greatest car chases in cinematic history. Its uncompromising bleakness and morally ambiguous protagonist prevent a perfect score for some, but they are precisely what make the film so powerful and enduring. It’s a high-octane shot of pure 80s cynicism that still feels dangerous.

To Live and Die in L.A. remains a brutal, brilliant piece of filmmaking – a sweaty, desperate sprint through the moral vacuum of 80s Los Angeles that leaves you breathless and maybe checking your wallet twice.