The name itself arrives like a whispered warning, tainted by association. Guinea Pig. Even now, decades removed from hushed video store exchanges and grainy nth-generation dubs, it conjures images of unspeakable acts presented with terrifying verisimilitude. You brace yourself, perhaps recalling the chilling rumours surrounding Flower of Flesh and Blood (1985), the tape Charlie Sheen famously believed depicted a real snuff film. But slip Guinea Pig 3: He Never Dies (1986) into the VCR, press play, and the expected wave of pure dread fractures, replaced by something far stranger, more unsettling in its sheer, bloody absurdity.

An Office Drone's Dark Discovery

Forget the grim pseudo-documentary horror of its predecessors. He Never Dies, helmed by writer-director Masayuki Kuzumi, veers sharply into the territory of grotesque black comedy. We meet Hideshi (Masahiro Satô), a seemingly ordinary, downtrodden salaryman grappling with workplace woes and romantic rejection. His life is a study in quiet desperation until, in a moment of profound despair, he attempts suicide... and fails. Not through intervention or a change of heart, but because, as he quickly discovers through increasingly graphic self-experimentation, he simply cannot die. Or even, it seems, feel much pain. What follows is not a descent into madness, but a bizarre, almost childlike exploration of his newfound immortality, played out with the kind of gleeful abandon usually reserved for cartoon characters, only here the anvils are replaced with kitchen knives and shards of glass.

Laughing Through the Lacerations

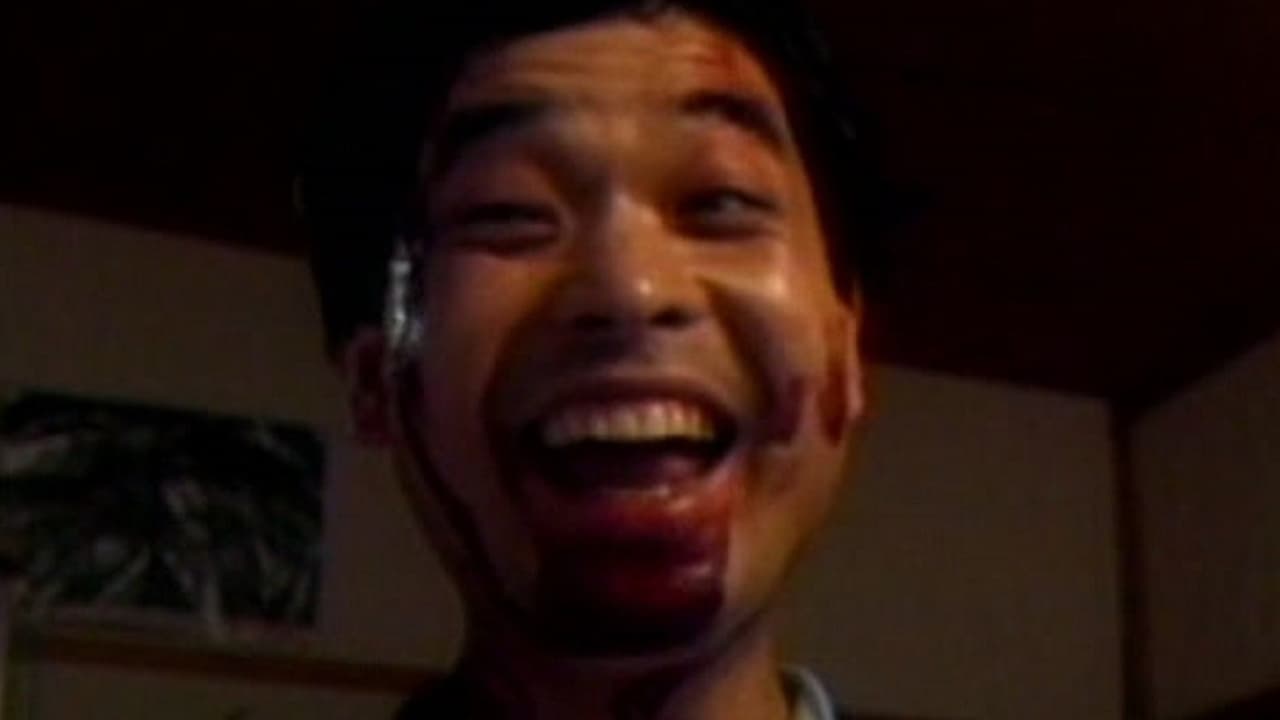

The film essentially becomes a one-man show for Masahiro Satô, who throws himself into the role with unnerving commitment. His performance is the lynchpin, oscillating between pathetic loneliness and a wide-eyed, almost gleeful curiosity as he systematically tries to injure himself in the most gruesome ways imaginable. It’s this tonal tightrope walk that makes He Never Dies such a peculiar artifact of the VHS underground. Are we supposed to be shocked? Horrified? Or... amused? The practical effects, while undeniably of their time, are pushed to the forefront. Buckets of stage blood, rubbery appendages, and crude but effective illusions of bodily harm are paraded with a strange lack of solemnity. Watching it now, the seams are visible, the tricks apparent, yet there’s an undeniable, morbid fascination in seeing just how far they’ll push the next gag. Remember how convincing some of those low-budget gore effects felt on a flickering CRT screen, late at night? This film weaponizes that memory, then twists it into a grim chuckle.

Beneath the Bloodshed: A Void or a Voided Point?

Unlike the nihilistic dread of Flower of Flesh and Blood or the surreal body horror of Mermaid in a Manhole (1988), He Never Dies feels almost... empty. Is there a deeper commentary lurking beneath the surface? Perhaps a jab at the soul-crushing conformity of Japanese corporate life, pushing Hideshi to find meaning only in self-destruction? Or is it simply an exercise in shock value, albeit one wrapped in comedic clothing? The film offers few clues. Its runtime is brief, its focus singular. Masayuki Kuzumi seems less interested in narrative or theme than in staging the next increasingly bizarre set piece of self-mutilation for Hideshi to perform for his bewildered (and ultimately terrified) colleague. There’s a certain purity to its absurdity, a commitment to its own strange logic that’s almost admirable in its sheer bloody-mindedness. Finding concrete behind-the-scenes details on this particular entry is tough, likely overshadowed by the controversies surrounding the earlier films, but its very existence speaks to the anything-goes nature of the direct-to-video market in Japan during the 80s, where extreme content could find an audience, even when twisted into unexpected shapes.

A Curious Cadaver in the Guinea Pig Canon

Within the notorious Guinea Pig series, He Never Dies stands out as the oddball, the black sheep painted crimson. It lacks the terrifying reputation of the second film or the more artful grotesquerie of some later entries. For gorehounds expecting the relentless grimness associated with the name, it might even feel like a bait-and-switch. Yet, its unique blend of extreme violence and deadpan comedy gives it a strange afterlife. It’s a film that defies easy categorization, existing in that uncomfortable space between horror and farce. Does that central performance, the sheer commitment to the escalating absurdity, still manage to get under your skin in a way traditional horror doesn't?

VHS HEAVEN RATING: 4/10

Let's be clear: this is not a good film in any conventional sense. It's repetitive, technically crude, and narratively threadbare. The 4/10 reflects its status as a fascinating, bizarre curio within a notorious series, primarily for Masahiro Satô's dedicated performance and its audacious, if ultimately shallow, commitment to its grotesque comedic premise. It utterly fails as traditional horror, offering little tension or genuine dread. However, its sheer weirdness and place within the controversial Guinea Pig legacy make it a memorable, if stomach-churning, footnote in the annals of extreme VHS discoveries.

It’s the kind of tape you might have unearthed from the "Under the Counter" section, expecting pure terror, only to be confronted with something profoundly, disturbingly silly. And perhaps, in its own strange way, that unexpected jolt is precisely why He Never Dies lingers in the memory, a perplexing stain on the tapestry of 80s horror oddities.